Formed at the margins where tectonic plates collide or diverge, seafloor massive sulphides are the most geologically active and among the most metal-rich deep-sea deposits. Only discovered in 1977 (though there were some tantalizing near misses several decades earlier), exploration on these prospects is relatively immature compared to formations like polymetallic nodule fields, which have seen nearly a century of speculation, experimentation, and discovery. More commonly referred to as hydrothermal vents in the broader deep-sea research community, seafloor massive sulphides are unique among potential deep-sea mining prospects in that they host novel ecosystems not found anywhere else in the ocean.

Though many contractors continue to make progress towards exploitation, seafloor massive sulphides saw an explosion of interest in the first decade of the 21st century which is now gradually tailing off in favor of the perennially appealing nodule fields. Of the 29 mining exploitation contracts issued by the ISA, only seven are for Seafloor Massive Sulphide deposits.

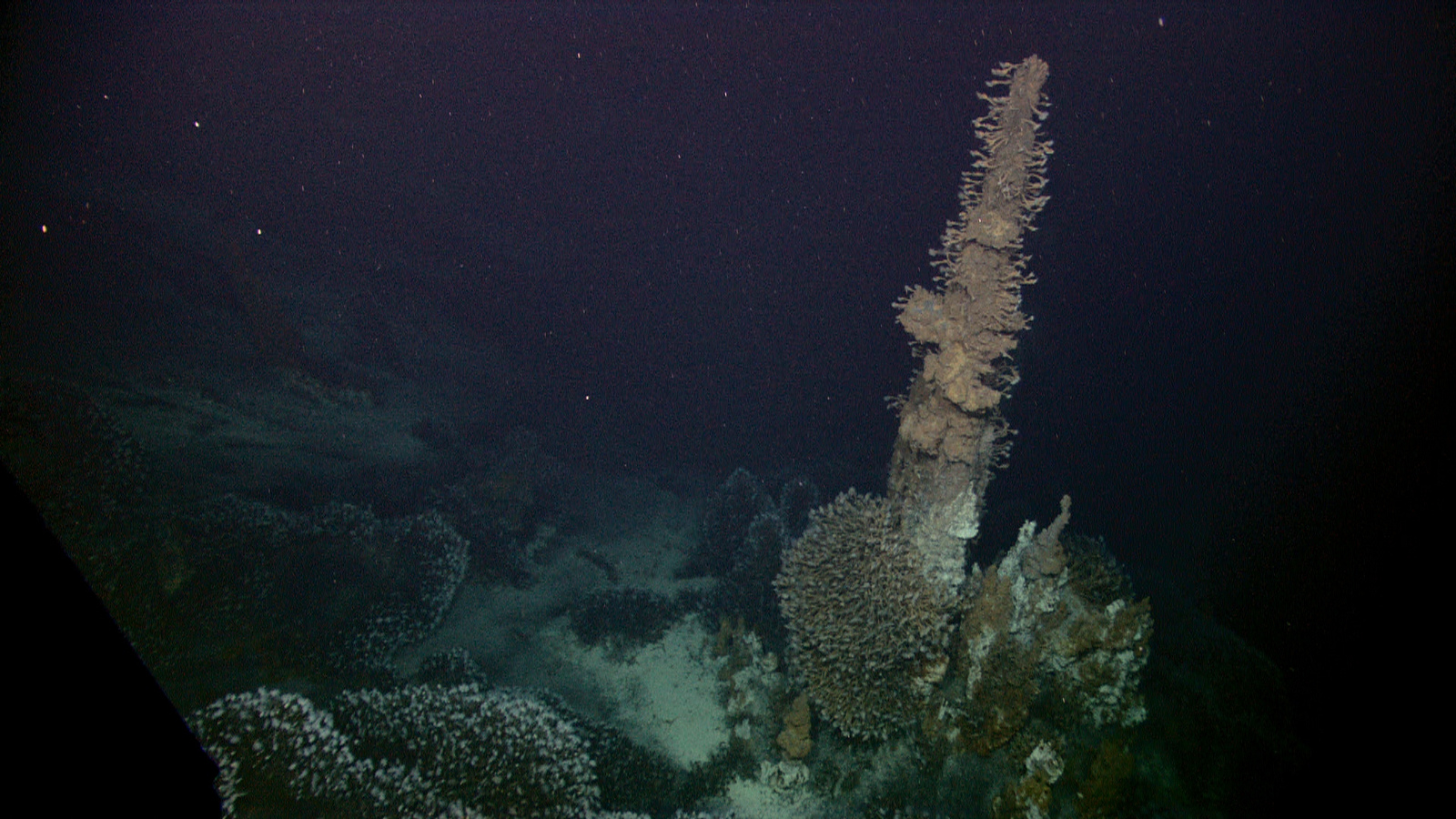

Seafloor massive sulphides are found throughout the world’s oceans at active plate margins and volcanic hotspots. They are particularly prevalent around the Pacific Ring of Fire as well as the Central Indian Ridge, East Pacific Rise, and Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Superheated water expelled from cracks in the planet’s crust contacts cold seawater, causing the heavy metals suspended in this effluent to precipitate out of solution, where it is deposited on the walls of a growing, mineral-laden “chimney”. These growing structures form the metal-rich deposits prized by deep-sea miners. Relative to polymetallic nodules and cobalt rich crusts, seafloor massive sulphides form fairly quickly in geologic time, prompting some to refer to these deposits as a “renewable resource”.

Seafloor massive sulphides present several technical and political challenges to deep-sea mining. They are topologically complex, requiring specialized equipment that can endure not just the rigors of underwater operation, but navigate steep slopes and rocky, heterogeneous terrain. They are geologically active, presenting one of the rarest hazards of working in the deep ocean: extreme heat. And they are politically more difficult to build stakeholder support for extraction, due largely to the most stunning feature of seafloor massive sulphides–the exceptional and exceptionally bizarre animals that thrive at hydrothermal vents.

Unlike nodule fields and cobalt-rich crusts, which are generally dominated by fauna common to the deep seafloor, seafloor massive sulphides support entire ecosystems which are dependent on the chemical energy emitted by the hydrothermal vent system. The same processes that make them enticing ore deposits also provide the foundation for communities of organisms so strange that their discovery triggered a sea change in our fundamental understanding of life on earth. The uniqueness and rarity of these ecosystems is the primary rationale behind the push for moratorium among some deep-sea stakeholder groups.

But the potential rewards from navigating the winding path towards production at seafloor massive sulphides can be tremendous. These ore bodies are not just rich in precious metals like copper, gold, and nickel, but in rare elements essential for sustainable energy technology. The small footprint of seafloor massive sulphides (the total surface area of active vent fields, globally, is roughly equivalent to the island of Manhattan) means a smaller, more concentrated operation than a comparably massive terrestrial metal mine. And the lack of overburden minimizes the production of tailings.

Seven contractors have active leases to explore seafloor massive sulphides in the Area. The Government of the Republic of Poland; Institut français de recherche pour l’exploitation de la mer (IFREMER); and Government of the Russian Federation all have lease blocks on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The Government of India; Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources of the Federal Republic of Germany; Government of the Republic of Korea; and China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association have lease blocks on the Central and Southeast Indian Ridge. In addition, several exploration permits have been issued in national waters, particularly in Small Island Developing States in the South Pacific, and one exploitation permit has been issued in Papua New Guinea for the Solwara I prospect, however that project is on indefinite hold as Nautilus Minerals restructures.

Featured photo: courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer