Opinion by Andrew Thaler, DSMO Editor-in-Chief

Deep-sea mining occupies a unique niche in the annals of extractive exploration. Its modern manifestation owes as much to the surging demand of critical minerals as it does to the work of environmental organizations shining a light on the vast environmental and ethical catastrophes of terrestrial mining. In its current form, deep-sea mining is an industry motivated by the need to rapidly wean ourselves from fossil fuels. It is, in short, an industrial response to an environmental crisis.

Whether or not it is the right response, for whatever “right” means in the midst of a global crisis while the clock is ticking, remains to be proven. No plans of work have been approved and no mining licenses have been issued by the International Seabed Authority for Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. What few attempts have been made in territorial waters have not reached production or have collapsed under the complexity of the operation. Deep-sea mining is an industry that has been perpetually just over the horizon. That horizon creeps closer every year.

There is an precarious partnership between deep-sea mining contractors and environmental NGOs, two entities with wildly differing views of what the world needs to reach sustainable development, but a recognition, at least in principle, that negotiation and compromise are possible. Even the calls for moratoria leave room for the possibility that deep-sea mining can be shown to be sustainable.

This uneasy truce between contractors and environmental NGOs has been tested over the last several months. With negotiations closed to most observers since February 2020, NGOs have taken to the sea and the streets to ensure that their stakeholders’ voices are heard. Protests at sea tested the patience of mining contractors, who felt that targeting their research program is counterproductive to the shared goal of understanding the environmental impacts of deep-sea mining. A campaign to get major companies to abstain from sourcing metals from the deep sea brought media attention and a threat to the industry’s profit projections. And a slew of bad press has put contractors on the defensive. All of which will create problems for consensus building when the ISA finally resumes in-person meetings.

But it is not just environmental NGOs placing this precarious partnership at risk. For the last few years, contractors and their sponsoring states have perennially threatened to force the ISA’s hand through an obscure procedural tool. Buried within the vast and complex 1994 Agreement on the Implementation of Part XI of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea is Annex I, Section 1(15), colloquially known as The Trigger. The Trigger provides a mechanism for a sponsoring state to initiate deep-sea mining in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction without a finalized mining code. A sponsoring state can submit a plan of work for commercial deep-sea mining, which starts a two-year countdown. If the Mining Code is not approved within those two years, the contractor and sponsoring state can begin mining under provisional, Council-approved regulations.

The trigger was built into the ISA founding documents as a failsafe mechanism for contractors who are ready to mine but waylaid until a Mining Code is approved. Envisioned as a tool to prevent procedural delays, its use is predicated on a contractor having the technological capacity to begin commercial production. A mining contractor with ships, seafloor production tools, and infrastructure in place, incurs tremendous operational costs whether or not those assets are in use. Without the Trigger, oppositional delegations could functionally filibuster the development of a Mining Code, while commercial contractors burn through their financial resources waiting in port. In short, the trigger exists so that a mining contractor can say “we are ready to mine, today. The only thing preventing us is the lack of a Mining Code.”

No contractor is ready to mine today. While the industry is resplendent in promising new technologies, it is all solidly enmeshed in the engineering, prototyping, and testing phase of development. For some, sea trials are underway. For others, there is still years of work to be done. The most optimistic estimates by the contractors themselves have near-complete systems entering sea trials by the end of 2021. Marine technology development is notoriously challenging, placing the earliest and most liberal estimates for a contractor to be truly ready to mine the deep-sea commercially by 2023, and that assumes every system within a vast and technologically complex array of robots, hydraulics, and humans, operating hundreds of miles from shore in thousands of meters depth, works flawlessly on the first attempt. The most optimistic projections have deep-sea mining contributing significantly to the global metals market near the end of the 2020s.

No full-scale seafloor production tools have completed their sea trials. No integrated riser and lift system has been deployed and tested. No vessel is ready to sail for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone to harvest polymetallic nodules at commercial scales. To pull the trigger now would be wildly premature.

Beyond that, pulling the trigger would be a stunning vote of no confidence in the International Seabed Authority, the Legal and Technical Commission, and the Council during a moment where herculean efforts have been taken to make progress on the Mining Code amidst a global pandemic that shut down in-person ISA meetings for a year and a half. The Trigger is no guarantee that the outcome will be beneficial for the contractor, either. A premature and rushed Mining Code could just as well favor tighter regulations than are strictly necessary or promote a payment regime that makes the enterprise far less profitable than it would otherwise be. “The regulatory uncertainties and political differences that could potentially arise as a result of pulling the trigger, resulting in a half-baked process that would need to be revisited in future, are certainly not favourable for investors looking to back prospective applicants for exploitation contracts”, Pradeep Singh said in an article we ran last year.

Often lost among the debates over technical capacity and policy minutiae involved in bringing deep-sea mining into production is an appreciation for just how revolutionary this negotiation is. Deep-sea mining will be the first industry of this scale for which the regulatory framework, particularly the environmental impact requirements, has been developed prior to commercial exploitation. It is a unique opportunity to develop an industry based on the consensus of the global community. No commercial exploitation at this scale has ever been developed with this level of participation and cooperation from industry, environmental NGOs, national delegations, and public and private stakeholders.

When finalized, the mining code, the standards and guidelines, and the payment regime, will provide not just the template for deep-sea exploitation, but set the precedent for the next phase of resource exploitation. How well the code works, how true it holds to the principle that these resources are held in trust for the common heritage of humankind, and how well these negotiations reflect the diversity of all stakeholders will be the standard by which all future exploitation beyond the reach of national borders are judged.

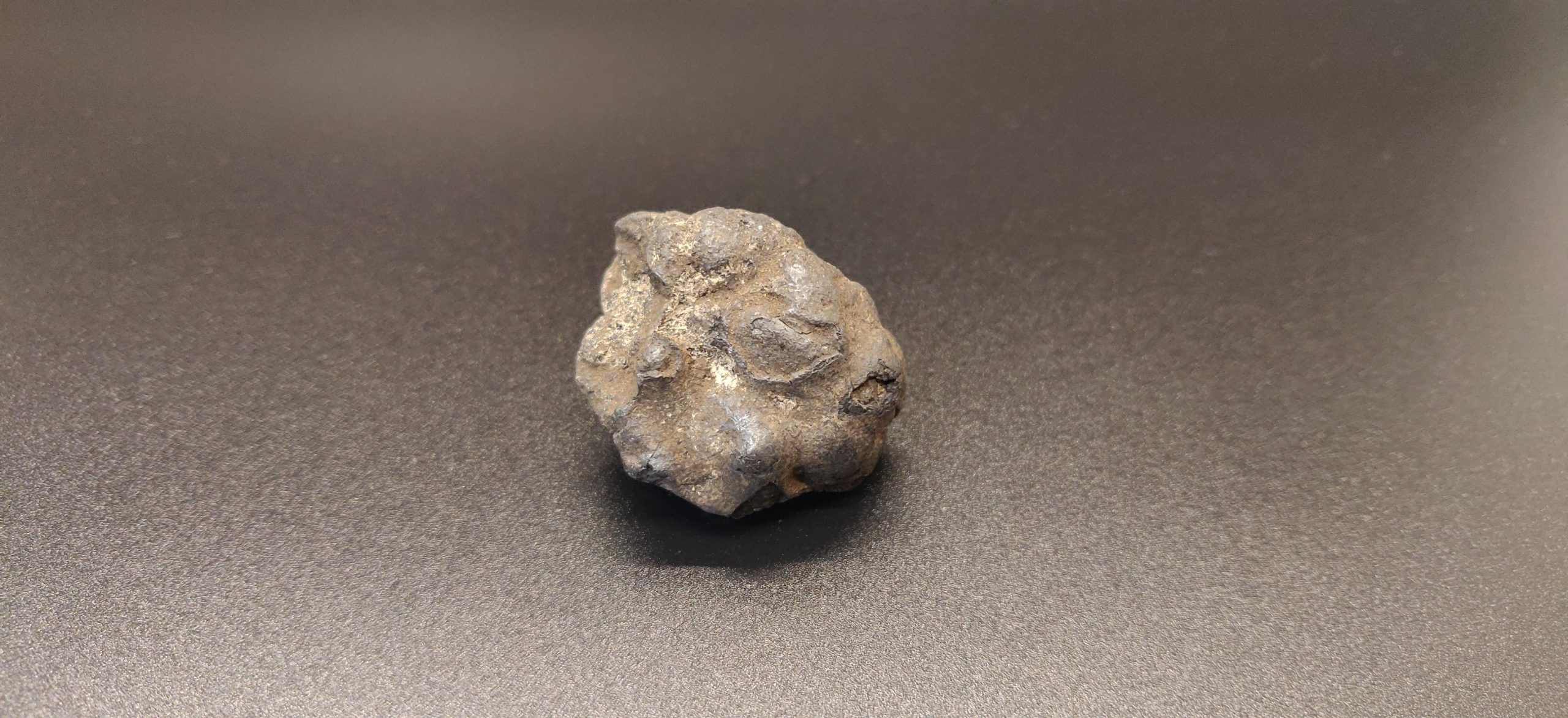

Just as deep-sea mining was a fantasy for Jules Verne 150 years ago, new industries are emerging from the seed of human imagination to shape the next generation of resource extraction. NASA’s Mars 2020 program will be the first to attempt a sample return mission from the red planet, recovering minerals from another world by 2030. Japan’s Hayabusa2 returned last December with samples from the asteroid 162173 Ryugu. The OSIRIS-REx probe is making its way back to Earth, rock samples from the asteroid 101955 Bennu in tow. And China’s Chang’e 5 mission has already returned 2 kilograms of lunar soil, the first lunar samples recovered in 40 years. As those industries mature over the next century, they will look to the negotiations, the laws, and the treaties that codified how the first modern extractive industry will operate beyond borders.

We only have one chance to get it right.