Maria Bolevich for DSM Observer

Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR) is founded by Deme Group, a world leader in dredging, marine engineering and environmental remediation. In 2013, GSR and the International Seabed Authority entered into a 15-year contract for the exploration for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Kris Van Nijen, the managing director of GSR, recently spoke at the World Conference of Science Journalists.During his presentation he discussed the difference between sustainable and responsible mining. “In terms of the extractive (mining) process, I want to ensure our operations are environmentally responsible. It’s a reminder we have a responsibility to take care of the environment.” explains Van Nijen.

In an interview for the DSM Observer Mr. Van Nijen shared his experience and views on deep-sea mining, challenges, myths, and also the impact of deep-sea mining on the search for new medicines.

DSM Observer: You are the managing Director of Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR) and “GSR aims to be a global leader in the responsible exploration and exploitation of polymetallic nodules” . How do you plan to achieve that, what is the most challenging part?

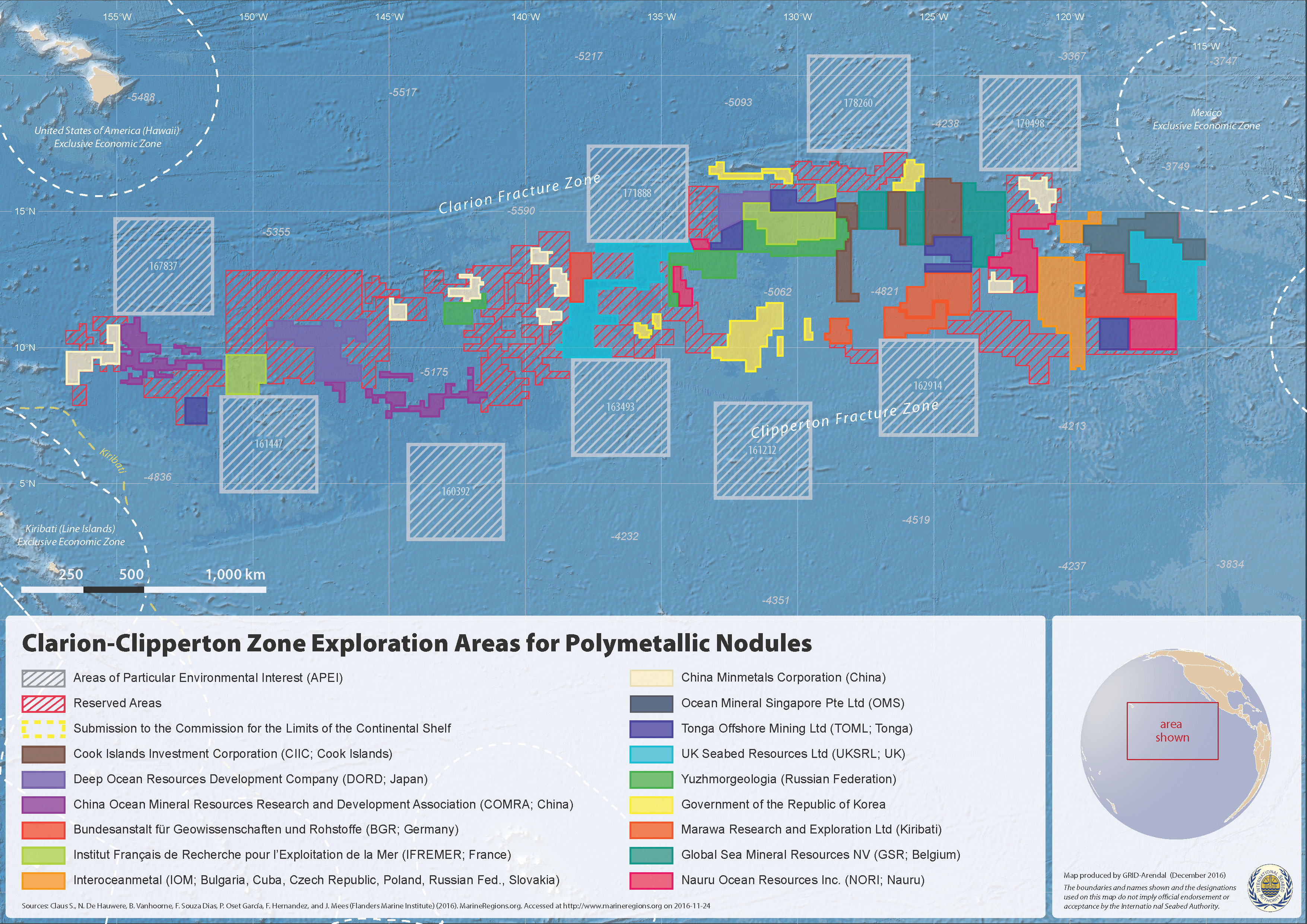

Kris Van Nijen: It’s worth drawing a distinction between the three different types of seabed mineral activity. Extracting minerals from seafloor massive sulphides and from cobalt crusts entails cutting into the seabed surface, but that is not the case with polymetallic nodules, small rocks which contain all the minerals used in clean energy technologies and which can be collected without digging into the sea floor. GSR is solely focused on collecting these nodules.We take a precautionary approach, collaborating with the scientific community to gather evidence about the impact of nodule collection on the marine eco-system. We began exploring our license area of the Clarion Clipperton Zone in 2013 and there will be many more years of exploration, research, review and refinement of technologies and processes before any commercial activity begins. We’re committed to transparency so all the environmental data we collect will be made available to the scientific community and we are participating in a joint research project involving 50 or so independent scientists. Our approach is to develop tailored, ecosystem-based management strategies to ensure that biodiversity and ecosystem health and function are maintained.

DSM Observer: NGOs are usually concerned about the impact, but as you mentioned there is “an independent research ship with 50 scientists sitting right by your side to monitor your respect for the environment”. What doesthe cooperation between a big company and 50 scientists look like?

Kris Van Nijen: Close co-operation with independent scientists is a founding principle of GSR. That is why we are pleased to be able to participate in “Mining Impact 2018-2022” an impartial EU-funded research consortium comprising GEOMAR and JPI Oceans. They will publish their research to ensure all knowledge gained is shared with the global community and informs management decisions. Key research objectives include improving understanding of sediment plumes and monitoring the direct and indirect impact of nodule collection. Dedicated monitoring surveys will take place in the area of nodule collection, the area where the sediment suspension occurs and in an ecologically similar non-impacted reference site. The sediment plume monitoring results will be used to validate an existing sediment transport model, which will inform the development of improved models and future environmental impact assessments.

DSM Observer: DEME invested 60 million euros in its deep-sea mining project, what was the most expensive part and why?

Kris Van Nijen: To date, the two most expensive parts have involved technology research and the development of the environmental baseline, both requiring dedicated exploration missions to the North Pacific Ocean. With regard to the technology, after successfully testing Patania I in 2017, this year, the Patania II encountered a problem with its communications cable (umbilical) during the testing phase. We are committed to being transparent about all things, successes as well as setbacks, and so of course we are open about the problems we encountered. We have now identified the root causes of the problem and are working on the solution. We are very much looking forward to Patania II’s next test. After a successful test of Patania II in 2020, GSR will have invested USD 100million. When regulations are in place in 2020, GSR will move to the system integration phase (feasibility phase), which will take another 2-3 years. Once all infrastructure is built, commercial production is expected from 2027.

DSM Observer: Why is the extraction of polymetallic nodules a good idea, especially when the growth of these nodules is very slow? What makes you worried?

Kris Van Nijen: We believe that establishing a seabed minerals industry is critically important for the planet. Moving to a low carbon future will see a huge increase in demand for metals used in clean energy technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, EV batteries and energy storage. Yet, land-based mineral resources are already stretched meeting the demands of global population growth and urbanization. Collecting nodules from the seafloor has many advantages over expanding terrestrial supplies. Unlike land-based mining there is no overburden (rock and soil) that needs to be removed to reach the minerals, no deforestation and no roads, railways or new ports are needed to export the ore. Terrestrial mining is becoming more complex, polluting and expensive as mines become harder to access. At a time when demand for metals such as nickel, manganese and cobalt is set to soar, the deep sea represents an important and responsible source of the additional minerals we need. It has been calculated that the Clarion Clipperton Zone holds 1.2 times more manganese, 1.8 times more nickel and 3.4 times more cobalt than all land-based reserves combined. What’s more, these metals are precisely the ones we need for clean energy technologies. These metals never appear all together on land so the deep sea is rather like having three mines in one location.We need to make choices based on evidence. We can’t get the minerals we need for energy transition and urban population growth without some degree of environmental impact. We need to understand what those impacts in depth are so we can make decisions based on data. Characterising one type of mineral source as good or bad is unhelpful and simplistic.

DSM Observer: Can you explain the process of obtainingexploration and exploitation licencesand how long the process takes?

Kris Van Nijen:Currently, GSR and other Contractors have contracts with the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to explore the seafloor for minerals and conduct environmental surveys. The contracts do not give anyone a right to mine and exploit the minerals. The research required during the exploration phase takes years to complete and includes an environmental impact assessment, which will culminate in an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The EIS, along with an Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan, and Closure Plan, must be submitted to the regulator (the ISA) as a part of the application for an Exploitation Contract. The earliest exploitation is expected to occur in 2027, still 8 years away.

DSM Observer:Scientists are worried about the impact of deep-sea mining on the search fornew medicine, what do you think?

Kris Van Nijen: Seabed mineral exploration contributes considerably to the advance of marine science. Many of the species that are being discovered today would have remained a mystery were it not for seabed mineral exploration. Marine scientific research can also reveal new marine genetic resources that may lead to the development of new antibiotics and drugs to treat cancer, Alzheimer’s, and cystic fibrosis, among others. Again, the seabed minerals industry can play a key part of the research effort in this important field. Deep-sea exploration is driving incredible advances in technology and innovation. In the same way scientific breakthroughs developed for space exploration have become ubiquitous in our daily lives – mobile phone cameras, scratch resistant lenses, water-filtration systems – our underwater activities are contributing to innovation in robotic vehicles, remote instrumentation, web services, computational data analysis and artificial intelligence.

DSM Observer:In general people are against deep-sea mining, what is/are the biggest myths about deep-sea mining?

Kris Van Nijen:There are probably three myths, or misunderstandings, worth identifying. First, as discussed earlier, there are three different types of seabed mineral activity, two of which involve processes traditionally associated with mining, i.e. cutting into the earth. This third type, polymetallic nodules, does not; rocks which are not attached to the seafloor are collected from the seabed. So, one of the misunderstandings arises from a failure to distinguish between these three approaches and a tendency to lump them together.

The second myth relates to the exploration phase and the commercial phase. We began exploring our license area of the Clarion Clipperton Zone in 2013 and there will be many more years of exploration, research, review and refinement of technologies and processes before any commercial activity begins. And yet it is often said that “we need to put a stop to deep-sea mining”. It hasn’t started yet and won’t for a long time. Never before has an extractive industry been subject to so much scrutiny or has such a precautionary approach to development been taken; never before has such a comprehensive regulatory regime been established before any commercial activity begins.

The final myth relates to supply and demand. The UN estimates that by 2100 there will be 11.2 billion people on the planet and two-thirds of that population will live in urban areas, putting huge pressure on already strained resources. Investment in sustainable infrastructure to support this growing and increasingly-urbanized population will be critical to economic growth and development and will have a major impact and demand for specific metals. And yet some still claim that it is possible to meet this demand using only terrestrial sources and recycling. Long-term, a fully circular economy is achievable, and the contribution of seabed minerals can play an important and responsible role. I believe they can help us reach these goals more quickly and more sustainably than if we relied on land-based resources alone.

DSM Observer: When you read science and environmental news what worries you the most and why?

Kris Van Nijen:What worries me most when I read science and environmental news is that sometimes the stories do not seem to be based on the best scientific evidence and sometimes stories can be unfairly emotive.Our job, if we are going to be responsible citizens of this planet, is for us all to be honest, transparent, for us all to share the knowledge we have gained and for us all, together, to make decisions about what is best – holistically – for our planet and its inhabitants. Based on evidence gathered to date, I know marine minerals have an important role to play in realizing a low-carbon future for our planet, in reaching many of our sustainable development goals, in helping to create a circular economy.

“We haven’t finished learning, and we look forward to sharing our learnings and learning from others as we continue to share our vision to supply the world with the minerals it needs to combat climate change and create a sustainable future for our planet,” concludes Van Nijen.

Featured photo: Kris van Nijen shows off the Patania II nodule harvester to ISA Secretary-General Michael Lodge. Photo courtesy van Nijen/GSR.