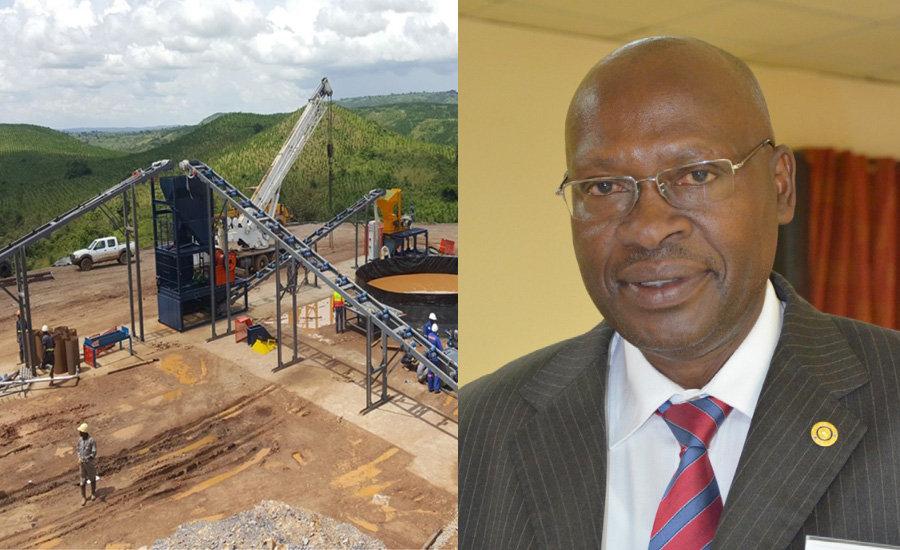

With over 30 years of service to the Ugandan Department of Geological Survey and Mines (DGSM), including the role of Commissioner from 2001-2010, geologist Joshua T. Tuhumwire brings a wealth of mineral and mining experience into his current role as the permanent representative of Uganda to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and a member of the ISA’s Legal and Technical Commission (LTC).

At the ISA, Mr. Tuhumwire represents much more than his own country’s view. He is both a technical expert and a champion for the UNCLOS commitment to the Common Heritage of Mankind, the legal tool under which all nations have equal access and an equal claim to the seabed resources that lie beyond national jurisdictions. Mr. Tuhumwire is an advocate for all ISA members as stakeholders in the Common Heritage of Mankind. .

Mr. Tuhumwire has extensive international experience, having served as a Member of the International Steering Committee for the African Rift Geothermal Energy Facility (ARGeo), the United Nations Ad Hoc Steering Group on Assessment of Assessments for the State of Marine Environment, and the United Nations Group of Experts for the Regular Process on World Ocean Assessment I.

In addition to his international responsibilities, Tuhumwire is the Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Gondwana Geoscience Consulting Ltd, based in Entebbe, Uganda. He also has been Chairman of the Board of Sipa Exploration Uganda Limited since June 2013 and is a current advisor to the Board of the Uganda Chamber of Mines and Petroleum.

DSM Observer spoke with Mr. Tuhumwire in December 2017 to get his views on the future of deep sea mining.

You represent Uganda to the International Seabed Authority, and also sit on the ISA’s Legal and Technical Committee. What unique perspectives do you bring to the global dialogue on deep seabed mining?

You represent Uganda to the International Seabed Authority, and also sit on the ISA’s Legal and Technical Committee. What unique perspectives do you bring to the global dialogue on deep seabed mining?

![]() I am from Uganda, however, members of the ISA’s Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) are elected on a regional basis, namely Africa, Asia, Caribbean-South America, Eastern Europe and Western Europe regions. I am one of five members that represent Africa. I am an exploration geologist with experience in mining law and mining regulations administration. I am also the only member of the LTC from a non-coastal or landlocked state, a status that strengthens the participation of landlocked states in accordance with what the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea envisions.

I am from Uganda, however, members of the ISA’s Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) are elected on a regional basis, namely Africa, Asia, Caribbean-South America, Eastern Europe and Western Europe regions. I am one of five members that represent Africa. I am an exploration geologist with experience in mining law and mining regulations administration. I am also the only member of the LTC from a non-coastal or landlocked state, a status that strengthens the participation of landlocked states in accordance with what the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea envisions.

When did you begin representing Uganda within the ISA? Have you observed changes to the organization and the momentum towards initiating deep seabed mining in the Area since you arrived?

When did you begin representing Uganda within the ISA? Have you observed changes to the organization and the momentum towards initiating deep seabed mining in the Area since you arrived?

![]()

Photo: ISA

I was elected in July 2016 and started my first term as a member of the LTC in March 2017. As a new member, I am on a steep learning curve and have no past experience with the organization’s performance. However, on interaction with fellow commissioners, I am informed there is huge momentum brought in by Mr. Michael Lodge, the new Secretary General of the ISA.

From your perspective, what does the future of deep seabed mining look like? What are the opportunities? The challenges?

From your perspective, what does the future of deep seabed mining look like? What are the opportunities? The challenges?

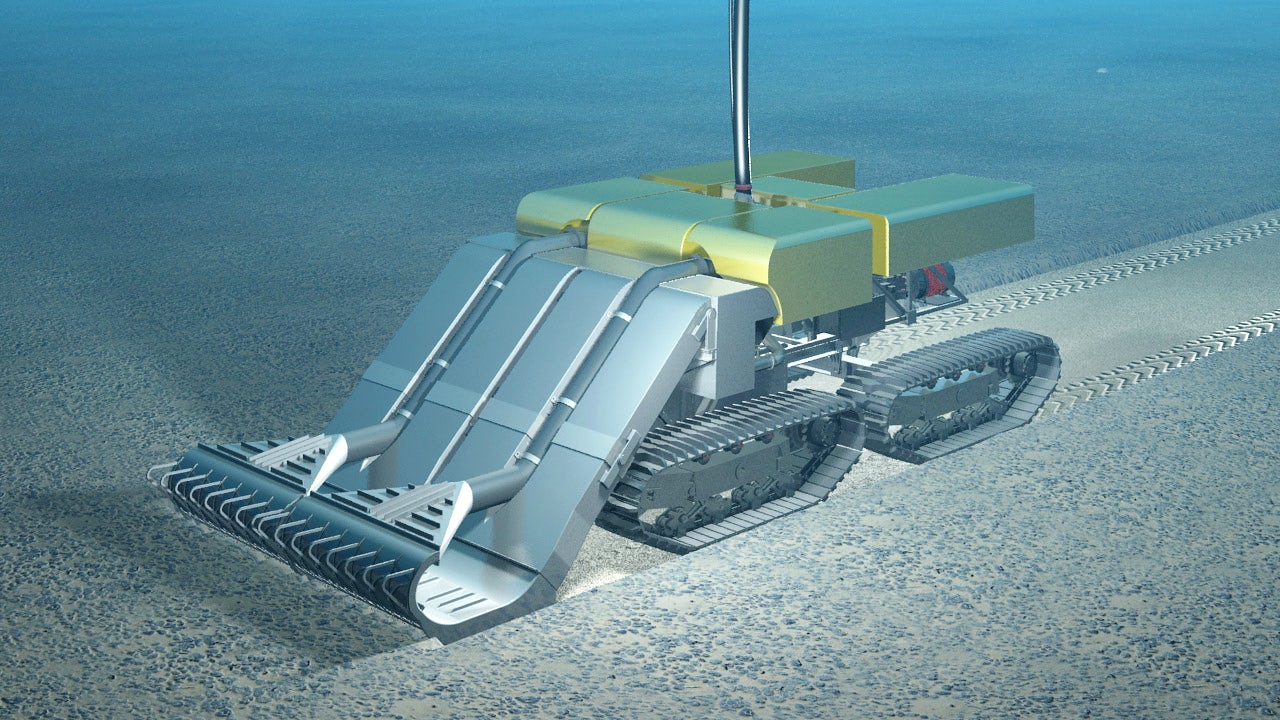

![]() From my perspective as a geoscientist, the future of deep seabed mining looks great. Since the Stone Age, all mankind’s mineral resource needs have been obtained from land, which is about 30% of the earth’s area. As a finite resource, many mineral commodities will be in short supply over the next few years. The oceans and seas represent 70% of the earth and the vast resources on the seabed therefore present a great opportunity to supply the mineral commodity needs of the future. The challenges of deep seabed mining are mainly two: the first is technology, which is under development and will soon be solved; the second, and most important, is the conservation of the ecologically sensitive ocean environment.

From my perspective as a geoscientist, the future of deep seabed mining looks great. Since the Stone Age, all mankind’s mineral resource needs have been obtained from land, which is about 30% of the earth’s area. As a finite resource, many mineral commodities will be in short supply over the next few years. The oceans and seas represent 70% of the earth and the vast resources on the seabed therefore present a great opportunity to supply the mineral commodity needs of the future. The challenges of deep seabed mining are mainly two: the first is technology, which is under development and will soon be solved; the second, and most important, is the conservation of the ecologically sensitive ocean environment.

Common Heritage of Mankind is a major component of the legal background and on-going development of the Mining Code. What does this concept mean to you and how might the global community be most faithful to the original intent when implementing it? Are there differences in how the framers of UNCLOS conceptualized the concept and how it is viewed today?

Common Heritage of Mankind is a major component of the legal background and on-going development of the Mining Code. What does this concept mean to you and how might the global community be most faithful to the original intent when implementing it? Are there differences in how the framers of UNCLOS conceptualized the concept and how it is viewed today?

![]() The concept of Common Heritage of Mankind is a major emphasis of the Mining Code under development and to me it has the same meaning in UNCLOS today as it had in 1982 when the Convention was signed. Accordingly, the Area and its resources are the Common Heritage of Mankind which means that the resources are vested in mankind, there is no claim to sovereignty and all States have equal access. There are likely to be differences within the global community in how the original intent is implemented based on the “haves” and “have nots”. However, it is anticipated that the Mining Code and Mining Regulations under development will have a financial modal to take care of the expectations of the States in the form of royalties and taxes.

The concept of Common Heritage of Mankind is a major emphasis of the Mining Code under development and to me it has the same meaning in UNCLOS today as it had in 1982 when the Convention was signed. Accordingly, the Area and its resources are the Common Heritage of Mankind which means that the resources are vested in mankind, there is no claim to sovereignty and all States have equal access. There are likely to be differences within the global community in how the original intent is implemented based on the “haves” and “have nots”. However, it is anticipated that the Mining Code and Mining Regulations under development will have a financial modal to take care of the expectations of the States in the form of royalties and taxes.

Are there specific needs for the development and implementation of the Mining Code that Uganda has as a land-locked Developing State that may differ from other types of State actors?

Are there specific needs for the development and implementation of the Mining Code that Uganda has as a land-locked Developing State that may differ from other types of State actors?

![]() Uganda like other developing and landlocked State parties have specific needs when it comes to deep seabed mining. Most Ugandans, even educated ones and those in government policy-making positions, have probably never seen the sea or even heard of UNCLOS. The starting point is for these countries to sign the Convention and domesticate it into national laws. While Uganda is a signatory, it has not domesticated the Convention into its national laws. The Mining Code has to cater to capacity building needs of these countries across various deep seabed disciplines including Law of the Sea, marine geology, mining technology, contract negotiation, protection of the environment, etc.

Uganda like other developing and landlocked State parties have specific needs when it comes to deep seabed mining. Most Ugandans, even educated ones and those in government policy-making positions, have probably never seen the sea or even heard of UNCLOS. The starting point is for these countries to sign the Convention and domesticate it into national laws. While Uganda is a signatory, it has not domesticated the Convention into its national laws. The Mining Code has to cater to capacity building needs of these countries across various deep seabed disciplines including Law of the Sea, marine geology, mining technology, contract negotiation, protection of the environment, etc.

What is your long-term vision for participation in the ISA? What does Uganda’s role look like once a Mining Code is in place and the industry begins to operate in the Area?

What is your long-term vision for participation in the ISA? What does Uganda’s role look like once a Mining Code is in place and the industry begins to operate in the Area?

![]()

Workshop held in Kampala, Uganda on 2-4 May 2017

Photo: ISA

My long-term vision for participation in the ISA is to deliver a good and acceptable Mining Code, inclusive of Mining Regulations and Environmental Management Regulations, to facilitate the development of deep seabed mineral resources. The ISA has embarked on an outreach exercise to raise awareness on its activities among state parties and held it first ever workshop in a landlocked country in Kampala, Uganda in May of last year. Uganda’s Permanent Mission in New York and the ISA Secretary General were very instrumental in this. The workshop raised the country’s awareness, a process which will continue going forward with my membership of the LTC/ISA. Once the Mining Code is in place and mining begins to take place in the Area, Uganda’s role in the short term could be that of a sponsoring state and eventually as a direct participant along the Tonga/Nauru model.

What advice do you have for other African States in regards to ISA participation? And are there things that the ISA can do to better engage and integrate new State actors from the African community?

What advice do you have for other African States in regards to ISA participation? And are there things that the ISA can do to better engage and integrate new State actors from the African community?

![]() It is very sad to note that many African states, even State parties to the Convention, are not actively participating in ISA activities at present. 47 African states are members of the ISA, of which 26 States are in arrears of contributions and 19 States have never attended an ISA meeting. There is also a conspicuous absence of African states either as sponsors or contractors in deep seabed mining. Out of about 28 contractors of the ISA, none are from Africa. For Africa to benefit from DSM, the States must fully participate in ISA activities instead of laying back and complaining in the future that the continent has been marginalized. They can be sponsors and/or sign exploration contracts with the ISA and take out exploration blocks in the Area such as Tonga, Nauru, Solomon Islands, India, Belgium, UK, Singapore, China and S. Korea to mention but a few. ISA can do better to engage new and old State actors alike by raising awareness of its activities and continuing to provide capacity building and training to nationals of African countries under the contracts.

It is very sad to note that many African states, even State parties to the Convention, are not actively participating in ISA activities at present. 47 African states are members of the ISA, of which 26 States are in arrears of contributions and 19 States have never attended an ISA meeting. There is also a conspicuous absence of African states either as sponsors or contractors in deep seabed mining. Out of about 28 contractors of the ISA, none are from Africa. For Africa to benefit from DSM, the States must fully participate in ISA activities instead of laying back and complaining in the future that the continent has been marginalized. They can be sponsors and/or sign exploration contracts with the ISA and take out exploration blocks in the Area such as Tonga, Nauru, Solomon Islands, India, Belgium, UK, Singapore, China and S. Korea to mention but a few. ISA can do better to engage new and old State actors alike by raising awareness of its activities and continuing to provide capacity building and training to nationals of African countries under the contracts.

Capacity-building, training opportunities and knowledge/technology sharing are important aspects of the ISA’s mandate to implement Common Heritage of Mankind. What’s your view on the current programme of work in these areas? What could be improved upon?

Capacity-building, training opportunities and knowledge/technology sharing are important aspects of the ISA’s mandate to implement Common Heritage of Mankind. What’s your view on the current programme of work in these areas? What could be improved upon?

![]() The current capacity building programme by the ISA is through internships for young professionals, under contracts on contractor cruises, and in some few cases contractors have offered scholarships. In my view this is a good programme but can be improved upon by increasing financial resources and hence the number of beneficiaries. In the future, a specific fund to build capacity of nationals of developing countries should be put in place.

The current capacity building programme by the ISA is through internships for young professionals, under contracts on contractor cruises, and in some few cases contractors have offered scholarships. In my view this is a good programme but can be improved upon by increasing financial resources and hence the number of beneficiaries. In the future, a specific fund to build capacity of nationals of developing countries should be put in place.

What’s your biggest challenge on the job? What would you most like to achieve for Uganda?

What’s your biggest challenge on the job? What would you most like to achieve for Uganda?

![]() Being new on the job is a challenge in itself. It is like going to swim for the first time and the bully student throws you into the deep end of the pool. The LTC is a mix of old and new members from different disciplines (lawyers, geologists, mining engineers, biologists, economists) and therefore at the beginning, discussion is often an exercise in learning to speak on the same page. There are so many documents to review and to discuss including new applications by contractors, annual reports of all existing contractors, and the draft Mining and Environment Management Regulations, all during the same 10 day working session. The work can simply seem too much and adding extra time at night and over the weekend is a necessity. I would like to see Uganda become a sponsor and/or contractor in the next 10 years. But first, awareness of UNCLOS by Ugandan policy makers is key.

Being new on the job is a challenge in itself. It is like going to swim for the first time and the bully student throws you into the deep end of the pool. The LTC is a mix of old and new members from different disciplines (lawyers, geologists, mining engineers, biologists, economists) and therefore at the beginning, discussion is often an exercise in learning to speak on the same page. There are so many documents to review and to discuss including new applications by contractors, annual reports of all existing contractors, and the draft Mining and Environment Management Regulations, all during the same 10 day working session. The work can simply seem too much and adding extra time at night and over the weekend is a necessity. I would like to see Uganda become a sponsor and/or contractor in the next 10 years. But first, awareness of UNCLOS by Ugandan policy makers is key.

When not at the ISA, your primary work is through your company, Gondwana Geoscience Consulting Ltd. Tell us a little about what you do there and what a typical day on the job entails. What kind of projects do you focus on and does this work help inform your role at the ISA?

When not at the ISA, your primary work is through your company, Gondwana Geoscience Consulting Ltd. Tell us a little about what you do there and what a typical day on the job entails. What kind of projects do you focus on and does this work help inform your role at the ISA?

![]() I incorporated Gondwana Geoscience Consulting Ltd in 2009, one year before retirement from Uganda’s civil service. My objective was to professionally remain alive in my retirement by offering knowledge, a long history in the mineral sector and managerial experience to the private sector. However, Uganda’s mineral sector has been in a downturn for the past four years for a number of reasons and, as such, there is very little mineral exploration taking place. In such a situation, retaining staff and paying office rent by a consultant can be a big challenge. Our focus is mainly on mineral exploration, tenement management, environment impact assessment and technical advice on mining law and regulations. In the current downturn, I spend more time in my office doing desk work and only occasionally go to the field. I am currently involved with First Republic Mining on a gold exploration project in the Lake George area of southwest Uganda, which is situated at the edge of a Ramsar Site, a game reserve and a forest reserve; and with Sipa Exploration Ltd/Sipa Resources on a nickel-copper project in the Lamwo-Kitgum area of northern Uganda. My key role in corporate governance issues on the two projects contributes to the experience I have in stakeholder engagement, mining law, mining regulations and environmental aspects, which together informs my role at the ISA.

I incorporated Gondwana Geoscience Consulting Ltd in 2009, one year before retirement from Uganda’s civil service. My objective was to professionally remain alive in my retirement by offering knowledge, a long history in the mineral sector and managerial experience to the private sector. However, Uganda’s mineral sector has been in a downturn for the past four years for a number of reasons and, as such, there is very little mineral exploration taking place. In such a situation, retaining staff and paying office rent by a consultant can be a big challenge. Our focus is mainly on mineral exploration, tenement management, environment impact assessment and technical advice on mining law and regulations. In the current downturn, I spend more time in my office doing desk work and only occasionally go to the field. I am currently involved with First Republic Mining on a gold exploration project in the Lake George area of southwest Uganda, which is situated at the edge of a Ramsar Site, a game reserve and a forest reserve; and with Sipa Exploration Ltd/Sipa Resources on a nickel-copper project in the Lamwo-Kitgum area of northern Uganda. My key role in corporate governance issues on the two projects contributes to the experience I have in stakeholder engagement, mining law, mining regulations and environmental aspects, which together informs my role at the ISA.

From 2001 to 2010 you served as Commissioner of Uganda’s Department of Geological Survey and Mines. What major challenges did you face there? What were your main achievements? How did this role inform your present work on the international stage?

From 2001 to 2010 you served as Commissioner of Uganda’s Department of Geological Survey and Mines. What major challenges did you face there? What were your main achievements? How did this role inform your present work on the international stage?

![]() As Commissioner of the Department of Geological Survey and Mines I led overall administrative oversight in addition to putting into effect provisions of the Mining Act. My main challenges came from clients (applicants for various licenses and license holders) as well as from politicians in the implementation of the law. The law and regulations clearly stipulate requirements and qualifications for an applicant. However, if an application was rejected for good reasons, some failed applicants would run to the Minister for intervention. In some situations, I received orders “from above” to grant licenses to certain individuals and companies, and in one instance to revoke a license without justification, which put me on a collision course with those officials giving the illegal orders. To that extent, I had to take early retirement 5 years prior to the end of my term. Nevertheless, I had many achievements in my 9 ½ years as Commissioner. When I took over in early 2001 the department was in shambles both in terms of infrastructure, staff morale and capacity building. I turned this around quickly and by 2004 the Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources Project, a US$ 47 million program co-financed by World Bank/IDA, African Development Bank, Nordic Development Fund and Government of Uganda was in place. High resolution airborne geophysical surveys over 80% of our country’s land area was carried out, new and more detailed geological and geochemical mapping undertaken, training of personnel both academic (BSc., MSc. and Ph. D levels) and on-the-job was undertaken, as well as construction and equipping of new offices and laboratories. Additionally, newly acquired geological and geophysical information was used to promote Uganda’s investment opportunities at various international mining conferences, a role that I spearheaded.

As Commissioner of the Department of Geological Survey and Mines I led overall administrative oversight in addition to putting into effect provisions of the Mining Act. My main challenges came from clients (applicants for various licenses and license holders) as well as from politicians in the implementation of the law. The law and regulations clearly stipulate requirements and qualifications for an applicant. However, if an application was rejected for good reasons, some failed applicants would run to the Minister for intervention. In some situations, I received orders “from above” to grant licenses to certain individuals and companies, and in one instance to revoke a license without justification, which put me on a collision course with those officials giving the illegal orders. To that extent, I had to take early retirement 5 years prior to the end of my term. Nevertheless, I had many achievements in my 9 ½ years as Commissioner. When I took over in early 2001 the department was in shambles both in terms of infrastructure, staff morale and capacity building. I turned this around quickly and by 2004 the Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources Project, a US$ 47 million program co-financed by World Bank/IDA, African Development Bank, Nordic Development Fund and Government of Uganda was in place. High resolution airborne geophysical surveys over 80% of our country’s land area was carried out, new and more detailed geological and geochemical mapping undertaken, training of personnel both academic (BSc., MSc. and Ph. D levels) and on-the-job was undertaken, as well as construction and equipping of new offices and laboratories. Additionally, newly acquired geological and geophysical information was used to promote Uganda’s investment opportunities at various international mining conferences, a role that I spearheaded.

In addition to mining-specific work, you’ve also served in international leadership roles dealing with ocean health and the environment. How did you first come to engage this aspect of ocean policy? What were the outcomes of some of the processes in which you were engaged? And what perspectives do you bring from that work that now inform your views and engagement on seabed mining?

In addition to mining-specific work, you’ve also served in international leadership roles dealing with ocean health and the environment. How did you first come to engage this aspect of ocean policy? What were the outcomes of some of the processes in which you were engaged? And what perspectives do you bring from that work that now inform your views and engagement on seabed mining?

![]() My dealing with ocean health and the environment was accidental. One day in 2006, I received a phone call from Uganda’s Permanent Mission to the UN in New York asking if I knew of any Ugandan expert in marine geology to join a team on the Assessment of Assessments for the Marine Environment. I replied that I didn’t know of any local experts. Months later, the Permanent Mission requested me to provide my CV, which I did. The rest is history. My work with the UN Regular Process on Reporting and Assessment of the Marine Environment over the years has greatly enriched my knowledge of the oceans to the extent that I deeply appreciate the sensitivity of ecological and environmental issues with respect to seabed mining.

My dealing with ocean health and the environment was accidental. One day in 2006, I received a phone call from Uganda’s Permanent Mission to the UN in New York asking if I knew of any Ugandan expert in marine geology to join a team on the Assessment of Assessments for the Marine Environment. I replied that I didn’t know of any local experts. Months later, the Permanent Mission requested me to provide my CV, which I did. The rest is history. My work with the UN Regular Process on Reporting and Assessment of the Marine Environment over the years has greatly enriched my knowledge of the oceans to the extent that I deeply appreciate the sensitivity of ecological and environmental issues with respect to seabed mining.

Who is the Joshua Tuhumwire outside the seabed mining world? What are your passions and interests? How do you spend your free time?

Who is the Joshua Tuhumwire outside the seabed mining world? What are your passions and interests? How do you spend your free time?

![]()

Photo: Rod Waddington, Wikimedia Commons

Outside the seabed mining world, I live as a retired civil servant who has “re-tyred” i.e., put on new tyres and I strongly believe that as long as one has energy do something, do it. Besides geological consulting and board work, my passion is growing trees/reforestation and I have a few hundred acres of forest in my home village in Rubanda, southwest Uganda. I strongly believe in service to the community and have been a member of the Rotary Club of Entebbe for 30 years and a multiple Paul Harris Fellow. In my free time, I play golf (single handicapper) and enjoy traveling the world, Bali and Thailand being my favorite destinations.