Harriet Harden-Davies | 15 November 2018

“This is a chance to take a course correction while we still can…if we pull together, we can make it”. Rena Lee, president of the intergovernmental conference—fondly referred to as Madame Captain—set an ambitious, positive and suitably nautical tone to open historic negotiations on 4 September 2018 at the United Nations in New York. This first session of the Intergovernmental Conference began formal negotiations to develop a new international legally binding instrument, under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in the two thirds of the ocean that lie beyond national jurisdiction

These negotiations follow more than a decade of discussions at the UN, including four Preparatory Committee sessions, which highlighted the need to better implement legal obligations relating to the study, protection and preservation of marine biodiversity. Fragmented and inconsistent sectoral and regional governance approaches have proved ill-equipped to cope as mounting pressures from resource exploitation are confounded by climate change impacts and pollution, and illegal, unregulated or poorly managed activities continue to wreak havoc on ocean ecosystems in the high seas. Consequently, this agreement is a key opportunity to boost global ocean conservation and science by empowering the international community with the tools to:

- Designate, monitor and manage area-based management tools, including networks of marine protected areas.

- Establish common governance principles and approaches for environmental impact assessments.

- Build capacity, translate marine scientific research and enable better uptake of technological innovation.

- Address access to marine genetic resources and clarify who should share in the benefits and how.

Reaching workable solutions on these highly technical issues and cultivating enough support is a challenging process. Although a positive atmosphere prevailed, some lamented that the Intergovernmental Conference represented a fifth Preparatory Committee rather than a negotiation. Some crucial issues remain, for example: decision-making processes for area-based management tools and environmental impact assessments, provision and implementation of scientific advice and the possible roles of a scientific committee, resources for capacity building and technology transfer, addressing cumulative impacts, relationships with existing frameworks and bodies, financial and institutional mechanisms, and monitoring and enforcement.

The devil will be in the detail. Two delegates remarked that the treaty will need to be “more than a paper tiger”, we need “a tiger with teeth—that can bite”.

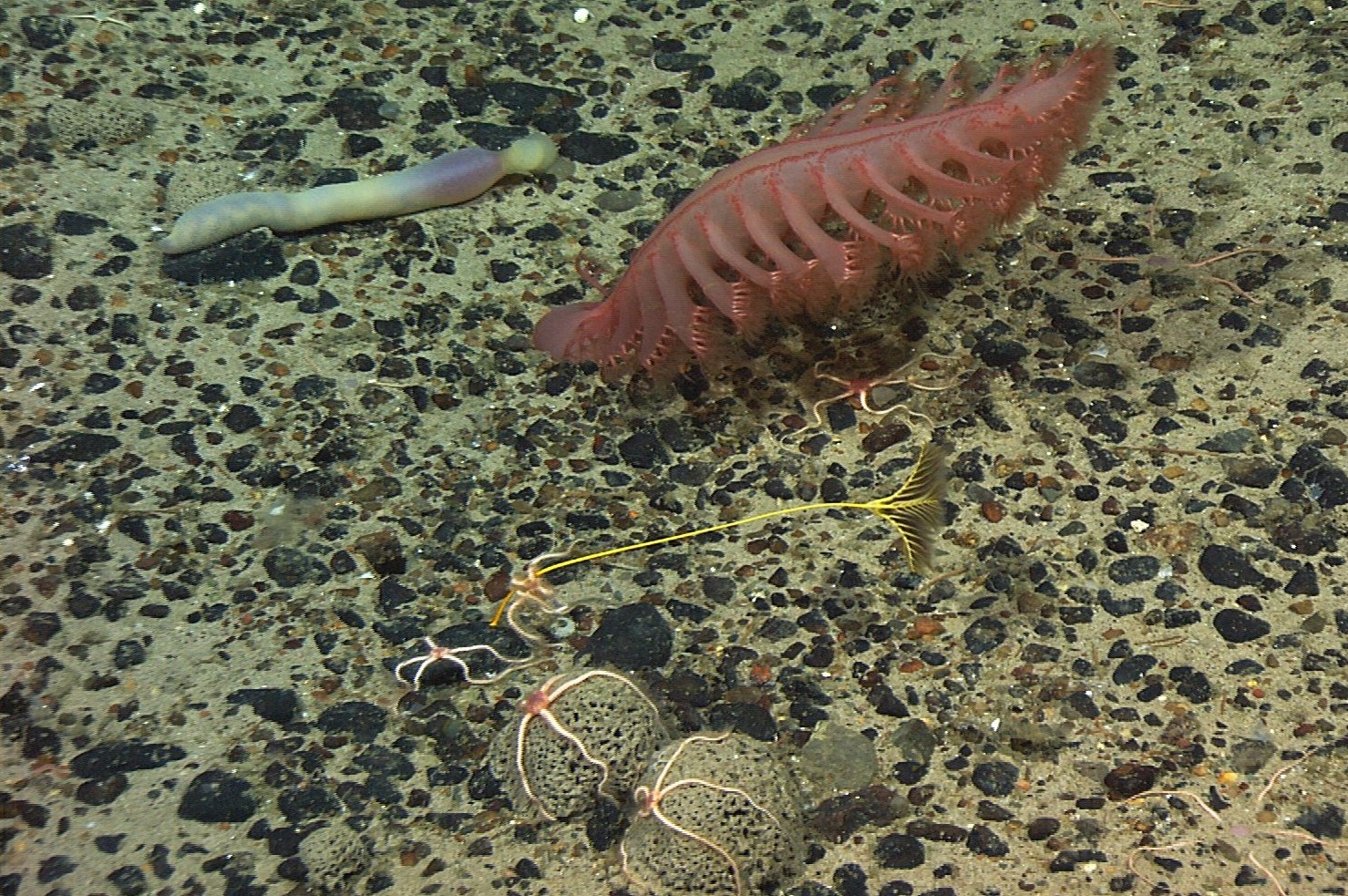

There is much that the scientific community can offer delegates to build ambition and momentum. Science is crucial to guide discussions on area-based management tools and environmental impact assessments as well as lift the veil on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction to explain what we need to better understand ocean life – from the sunlit surface to the abyssal depths.

As many delegates highlighted, science and scientists will continue to be crucial to shape solutions on marine genetic resources. Options proposed by the G77 and China for access and benefit-sharing consistent with the regime of the high seas represented a significant step forward in this negotiation. Sharing scientific research results, transferring technology, and building capacity are central to these options. The next step is to develop concrete proposals that help yet do not hinder marine scientific research, including: the feasibility of notification, tracking, tracing and sharing of biological samples and associated data.

Regarding capacity building and technology transfer, science will be central to any strategy to facilitate knowledge advancement, ensure inclusive and transparent participation, and provide the knowledge, technology, tools, and mechanisms needed to study and sustain marine biodiversity. The development and deployment of technologies will be key to observe how ocean ecosystems and human activities in the high seas interact and respond to change. New mechanisms such as a clearinghouse could support capacity building, however, to be lasting and meaningful it is crucial to identify the needs of a range of stakeholders – from individual scientists to States.

Three more sessions of the Intergovernmental Conference are scheduled between now and 2020, the second conference will be held 25 March – 5 April 2019 at the UN in New York. We can expect a document from President Lee in early 2019 to facilitate text-based negotiations. We are all in the same boat and as one delegate remarked, “smooth seas don’t make good sailors… we will be very good sailors by 2020.”