The Rio Grande Rise is an almost completely unstudied, geologically intriguing, ecologically mysterious, potential lost continent in the deep south Atlantic. And it also hosts dense cobalt-rich crusts.

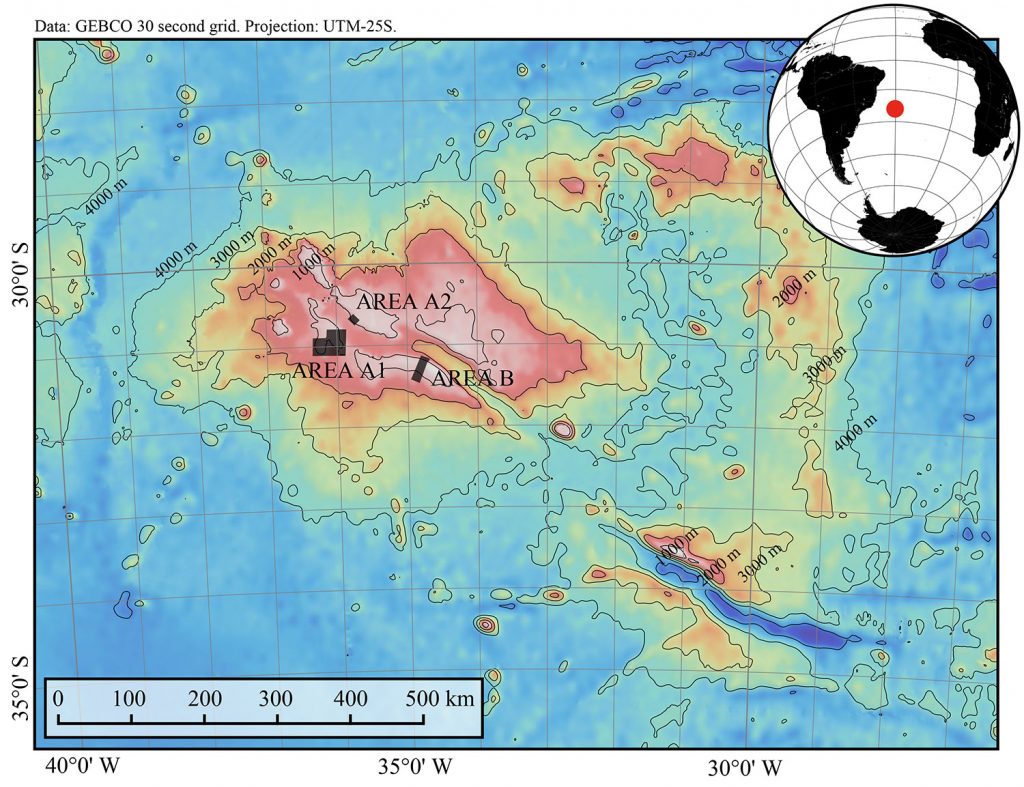

The Rio Grande Rise is a region of deep-ocean seamounts roughly the area of Iceland in the southwestern Atlantic. It lies west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge off the coast of South America and near Brazil’s island territories. As the largest oceanic feature on the South American plate, it straddles two microplates. And yet, like much of the southern Atlantic deep sea, it is relatively under sampled.

Almost nothing is known about the ecology or biodiversity of the Rio Grande Rise.

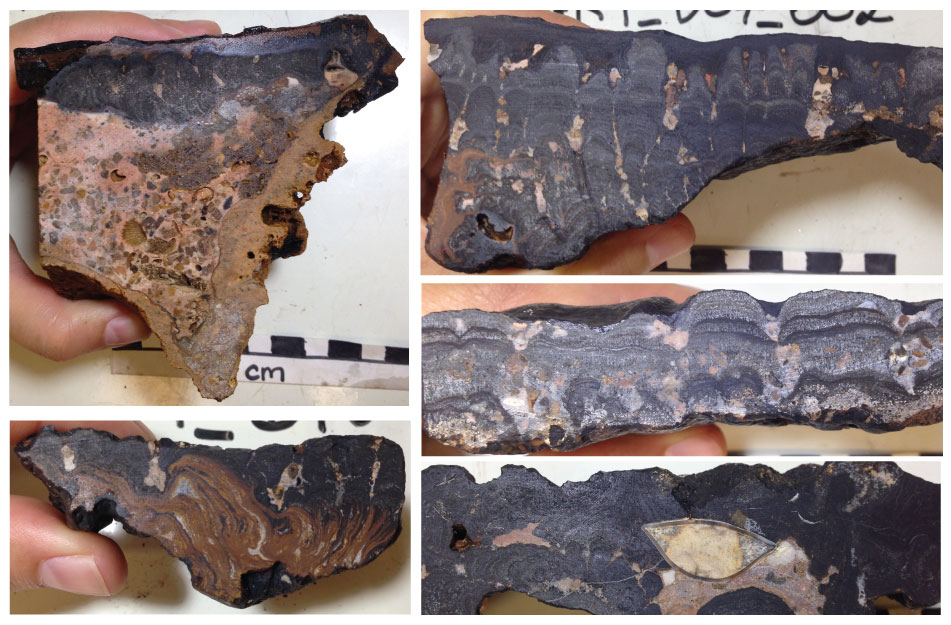

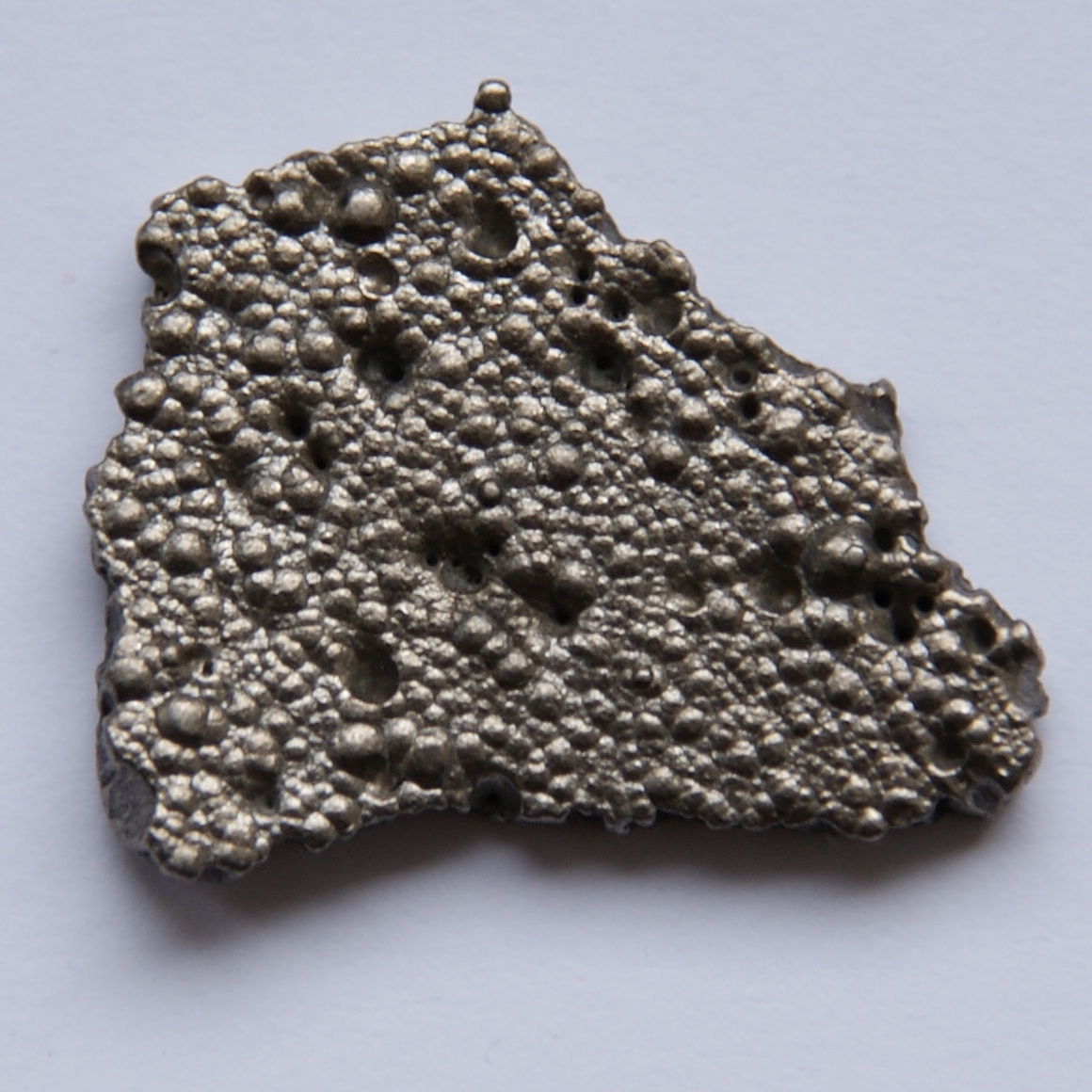

A recent study attempts to rectify that knowledge gap and provide insight into how deep-sea mining for cobalt-rich crusts will impact these almost completely unknown ecosystems. The Rio Grande Rise is inhabited by a diverse collection of predominantly sessile organisms that grow slowly on the even-slower accumulating crusts. Surprisingly, the Rise appears relatively free of pollution or human disturbance, likely due to the low productivity of the ocean above. The seamounts that rise from a 6000-meter basement to just below the surface provide the perfect conditions for the formation of cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts.

Cobalt-rich crusts tell a story about the history of an ocean. They accumulate slowly over millions of years creating an archive in stone of past ocean conditions. These crusts are rare in the Atlantic, a relatively young ocean created by the massive rifting along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where hydrothermal activity limits crust formation. The Rio Grande Rise may itself be an aborted spreading center, its numerous seamounts are, as far as we know, free of hydrothermal venting.

When granite boulders were dredge from the seafloor, scientists speculated that the Rio Grande Rise might be formed from continental crust, suggesting, much like the recently revealed Zealandia, a lost continent in the South Atlantic. Seismic reflection data points towards the presence of continental material buried beneath more recent deposits. Though more granite formations were observed via submersible, follow-up studies have been inconclusive.

Headlines that play off the Lost Continent of Atlantis aside, establishing whether the Rio Grande Rise is formed from continental rather than oceanic crusts may have important implications for future ocean policy. Under UNCLOS, nations may claim an exclusive economic zone over their continental shelf. When that shelf extends far beyond the 200-mile limit, nations can still claim seabed resources beyond the limit of the EEZ. This phenomenon is currently being tested in the Arctic, where in 2016 the Russian Federation petitioned the UN for oil and mineral rights extending to the high Arctic (Russia famously planted a flag on the seabed near the north pole as a preamble to this claim). The UN rejected the petition, but Russian continues to push for expanded rights in the Arctic.

Likewise, Brazil-backed exploration on the Rio Grande Rise has been conducted with the explicit goal of establishing whether its origins are continental, allowing Brazil to lay claim to this region. From a summary of the Iatá-Piuna Expedition to the Rio Grande Rise conducted in 2013:

“The new expedition confirmed that it was no mistake and that the Rio Grande Ride is most probably a sunken continental mass that some are dubbing as Brazil’s Atlantis. Although the age of the granite samples was not disclosed, researchers agreed that it was certainly older than other rock samples found on the seafloor. The samples also indicated that there were possible deposits containing iron, nickel, manganese, cobalt, niobium and tantalum. There is also the possibility of methane gas deposits and possible even oil, yet future deepwater drilling expeditions will have to look into that. This expedition also serves another purpose for the Brazilian Government, as it intends to claim this area as part of its exclusive economic zone.”

Marine Technology News, 2013 (emphasis DSMO)

The consequences of mining cobalt crust on the Rio Grande Rise include the complete removal of substrate essential to benthic species, smothering by localized plumes, crushing of sessile organisms by tailings, and the release of toxic heavy metals. The consequences of Brazil successfully laying claim to resources that currently fall under the regulatory oversight of the ISA could open the door for other territorial expansion into the high seas.

Companhia de Pesquisa de Recursos Minerais, a Brazilian state-sponsored geological research organization, has a 15-year exploration lease on the Rio Grande Rise to investigate the viability of harvesting cobalt-rich crusts.

Read the paper here: Deep-sea Mining on the Rio Grande Rise (Southwestern Atlantic): A Review on Environmental Baseline, Ecosystem Services and Potential Impacts.