Significant changes loom ahead in the new year and beyond for deep sea mining. Despite Nautilus’ setbacks this year, progress elsewhere appears to continue moving inexorably forward. At this crucial juncture, asking how we can ensure deep sea mining develops down a pathway ending in good governance and an environmentally-sound world is as important as ever. As graduate students in the Environmental Change Institute at Oxford University, we engaged in research to set out and map the system currently emerging.

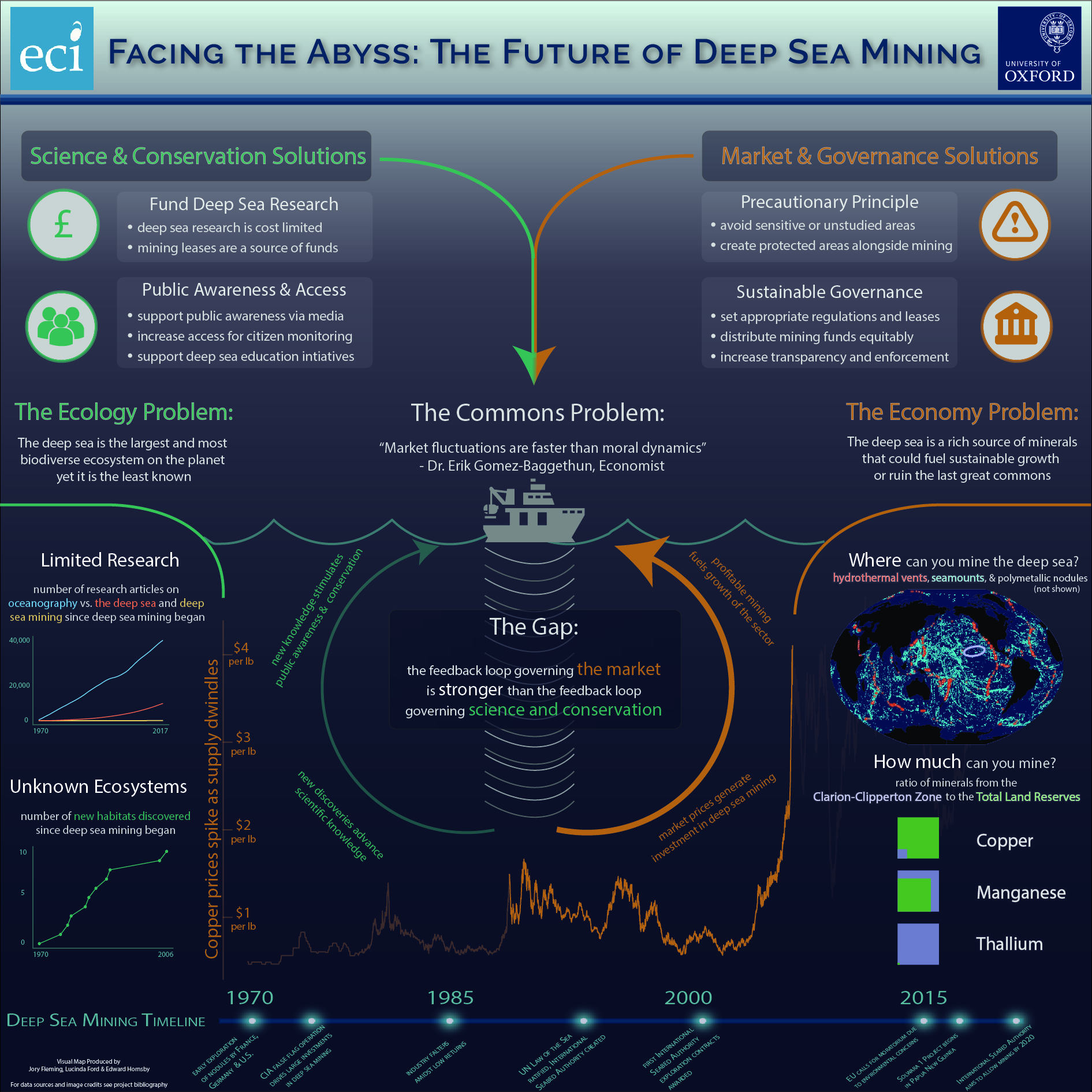

Summarized in our system map below, our research identified two key feedback loops:

- Demand and prices of high value metals will likely rise in the coming decades, generating an increase in deep-sea mining and its profitability.

- As new scientific discoveries emerge, the increased knowledge can result in public awareness, conservation efforts, and a desire for further research.

These feedback loops do not appear balanced. Scientific knowledge and conservation efforts in the deep sea accumulated slowly compared to the speed of the mining industry. Correcting this imbalance should result in a more sustainable and stable system. Many actors have a role to play in the solution: the market can better self-regulate through standards and a vision of corporate social responsibility, and governmental institutions can act to increase research funding and address fragmented regulatory regimes.

A key actor, the public, seemed to be missing from the system. As we spoke to experts in academia, government & policy it was not long before we found why. The deep sea is chronically underrepresented in media and public discourse, but as one expert, Dr. W. Joe Jones, put it: “how we view the ocean determines how we treat it.” The ocean floor is often distant from the public conscience, both literally and figuratively. Direct contact is usually limited to small and highly specialized interest groups, such as subsets of the fishing community. While the public may have a good awareness of the importance and beauty of shallow-sea systems like coral reefs, it is generally less versed in deep sea biology and the many fascinating creatures, such as these bone-eating worms.

A face only a mother could love? Osedax rubiplumus. Photo credit Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

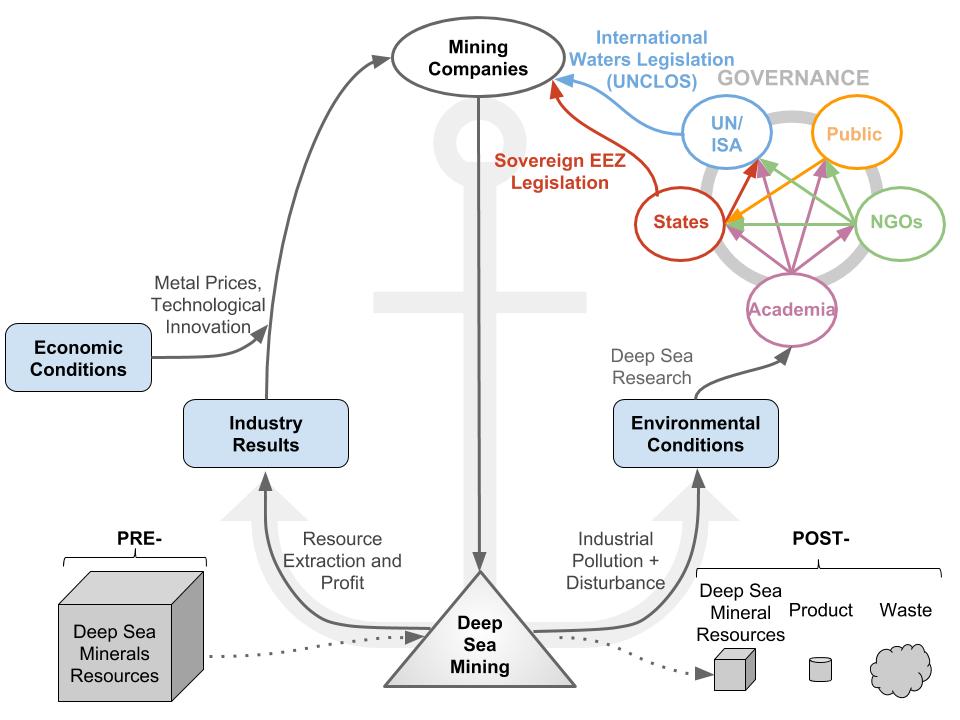

A disengaged public has minimal leverage to shape the actions of other actors in the system. In a systems framework the standard tools at a policy maker’s disposal, including regulation, economic incentives, and industry codes and standards, are less able to change the underlying structure that governs how the system and its actors operate. Here we envision the current actors in a systems diagram, and a disengaged public is channeled via NGOs, governments and other institutions to mining companies. We do not think this leads to a sustainable future for deep sea mining.

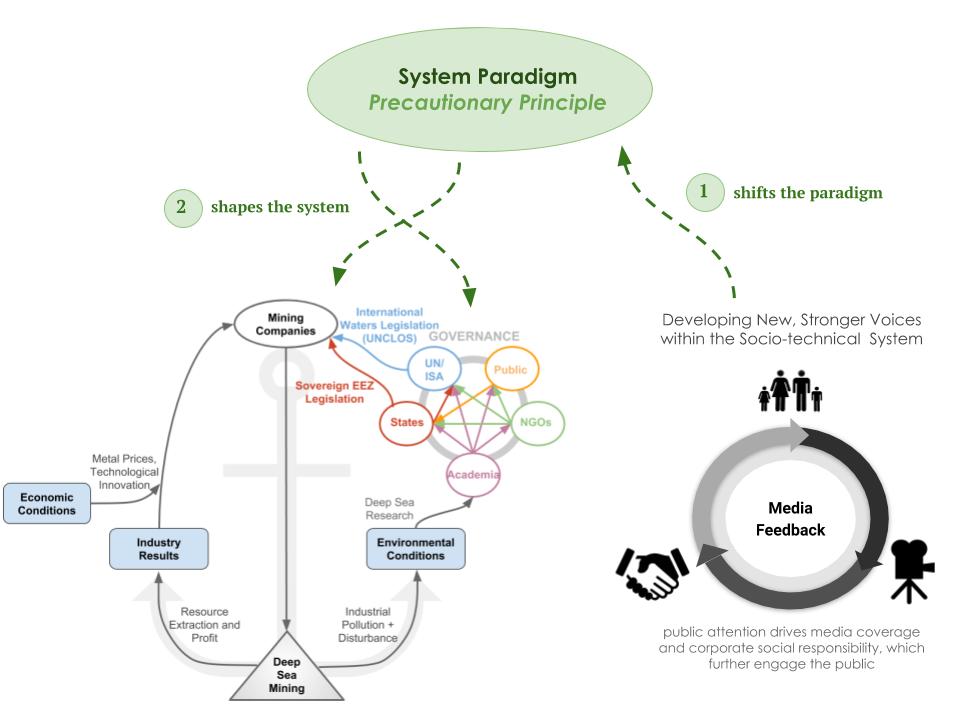

We envision a way for the public to fundamentally shift how the system operates. A powerful way to create change is to change the paradigms underpinning the system. Doing so subtly changes the power balance between the actors and what is or is not permissible. We can reimagine the current system by stepping outside it and creating a new, self-reinforcing cycle. An increase in public awareness, attention, and activism can foster increased media attention and significantly greater incentives for companies to engage in corporate social responsibility. This cycle engages and connects a wider audience to the issue, and it has the power to demand that a certain mindset, such as the precautionary principle or sustainable development, govern the system actors. Ultimately, by engaging with these values and increasing its expectations, the public begins to gain leverage over how the resource is managed, whether in a country’s waters or in those areas governed by the International Seabed Authority.

The power of this model was recently demonstrated in the UK. The launch of Blue Planet 2 on the BBC generated intense public interest in marine plastics pollution, which can be seen in a Google Trends search spike corresponding to the series’ debut in late 2017. The ripple effect of this public scrutiny influenced leading industry figures such as the Co-operative to adopt ambitious new CSR standards and increased parliamentary engagement with the issue. While some are dubbing this the “Attenborough effect” it is not the only time this phenomenon has been observed. The UK’s battle with waste is just one example of the efficacy of bringing social science theory to bear on systemic environmental management.

A paradigm of public engagement can and should be implemented for deep sea mining. If the deep sea is truly set aside for “the common heritage of mankind”, the public needs to be engaged immediately. The great news is that everyone can play a small role in fostering communication amongst the public about the deep sea, its wildlife and habitats, and those companies trying to utilise its resources sustainably. Initiatives like Diva Amon’s and National Geographic’s “My Deep Sea My Backyard” have the potential to bring in new voices that can reshape the system. As a member of the DSM Observer community you’re already plugged into the system, how will you change it?

For more, our full report and bibliography are on Figshare.