Maria Bolevich for DSM Observer

The coronavirus pandemic is changing the world in dramatic and subtle ways, exacting a toll measured both in lost lives and economic uncertainty. Deep-sea mining has been in development for over 50 years and now, at the moment in which negotiations were poised to transition the industry from exploration to exploitation, the Covid-19 Pandemic threatens half a century of progress. To better understand how the pandemic is impacting deep-sea mining in practice, we reached out to experts from across the deep-sea mining community for their views on the challenges faced by the industry and the steps being taken to ensure that progress continues even in quarantine.

“For this newborn industry, the slowdown in the global economy is creating a great deal of uncertainty about its future step forward.” says Jean-Marc Daniel, head of Ifremer’s Physical Resources and Deep-sea Ecosystems Department. For Ifremer, the most difficult component is keeping the teams organized, maintaining group morale while working from home. Most of the technical work involving laboratory analysis are currently stopped explains Jean-Marc Daniel.

Last month the DSM Observer reported on the pandemic’s effect on negotiations; it was clear that deep-sea mining will face a process delay. Conn Nugent a senior fellow at the Ocean Foundation says that one clear impact is that the pandemic will hinder the International Seabed Authority’s rule making process. For example, there are too many concerned parties opposed to decision-making via-video conference. Less clear is whether contractor exploration activities will be affected by the pandemic. “For corporate contractors, we might anticipate that the pace of exploration will be slowed. It will be tough to carry on what is an expensive activity during a time of widespread corporate belt-tightening. For state-owned contractors it’s harder to say. My guess is that their current rate of exploration activities will continue.” Nugent adds.

When it comes to the future of the industry, Jean-Marc Daniel says that development will certainly be shifted in time, the economic incentives are going to be very low after the coming economic crash and that rethinking the globalized economy in response to this crisis could result in the rapid growth of renewable energies. “This could perhaps create new opportunities for this industry” said Daniel.

Historian Ole Sparenberg based at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, is a post-doctoral scholar at the Gerda Henkel Foundation researching the history of deep-sea mining. Last year he published a“A historical perspective on deep-sea mining for manganese nodules, 1965–2019” in which he explored the history of deep-sea mining. Deep-sea mining has faced challenges throughout its history and, to date, commercial exploitation of polymetallic nodules or any other deep-sea mineral resource has not been realized.

“I think it depends on the impact of the pandemic: will we see a drastic, but short shock with a subsequent quick recovery or will the pandemic be the trigger that starts a long-lasting recession?” says Sparenberg. “In the first case, the consequence for metal demand will be limited, in the second case obviously not. At the moment, I tend to the second case and expect a more prolonged recession. This would obviously depress demand and prices for key deep-sea resources like nickel and copper.”

In a worst-case scenario, the pandemic triggers a long-lasting ‘de-globalization’ with reductions in free trade and major states competing for exclusive control over resource-exporting areas. In this scenario, deep-sea mining might gain importance for strategic reasons.

“At the moment, however, I think it is remarkable that nickel and copper prices have not dropped that sharply since January. As far as I can see, and unlike crude oil which dropped by 50%, prices of base metals are still at more than 80% of their price from January 2020.” says Sparenberg.

According to Sparenberg, long term effects are harder to predict, and a lot will depend on the time horizon of investors. Most investors likely never expected to start mining polymetallic nodules before the second half of the decade. Deep-sea mining operations are planned to run for 20 years or more, what will happen the next five years or so, is not necessarily decisive for the fate of deep-sea mining. On the other hand, raising venture capital may be difficult in the near future. “And finally,” adds Sparenberg, “of course the project of deep-sea mining might be postponed again indefinitely like in the early 1980s. There are projects like supersonic airliners or space travel to the Moon or Mars that pop up again and again and are feasible in principle (or even briefly have become reality in the past) yet never seem to make the breakthrough.”

From the point of view of environmentalists and marine biologist, any postponement of deep-sea mining would be a welcome respite. In the 1980s, commercial interest in polymetallic nodules waned which created time and opportunity for ecological research on baseline conditions and environmental impact studies like the DISCOL experiment. Postponement today may create an opportunity to thoroughly research how to minimize the environmental impact. “On the other hand and seen from a somewhat cynical point of view, the pandemic might be an opportunity to pass the mining code and other regulation on the level of ISA and national states at a time when a broader public in the West is occupied with the virus and its impact and won’t pay much attention to environmentalist NGOs.” concludes Sparenberg

Professor of Economics Federico Foders of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, doesn’t see a major disruption coming because of the coronavirus. He explains that after a pandemic-induced global recession the world economy needs a jumpstart and the indication is that the demand for natural resources from the seabed will increase. When it comes to the protection of the industry, Professor Foders says that there is a legal mining regime established by the UN and managed and regulated by the ISA and that activities ocurring within this framework are protected. “We should not forget that according to the Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS) seabed resources in the high-seas area (outside of coastal countries’ national jurisdiction) belong to the common heritage of mankind and not to individual countries. Also, the results of research done in the context of deep-sea mining will be very useful for a number of other ocean uses in the future.“ says Foders.

Professor Foders sees demand for seabed resources recovering during an upswing in 2021-2022 and deep-sea mining could play a key role then. Currently some potential seabed resources are only available from a small number of land based producers with strong market positions. When deep-sea mining comes on line, the market power of land based producers will be somewhat eroded by the creation of new sources and by increased competition among suppliers. When it comes to the future of the deep-sea mining industry, Foders says that the future is closely related to the ability of the UN/ISA to complete the financial terms for companies operating within the UN regime without creating any disincentives. Once the fiscal regime has been completed and implemented, the environmental impact of deep-sea mining will present an important challenge for the UN/ISA as well as participating countries and contractors. “Of course” he says “the environmental challenge is also faced by mining companies operating outside of the UN regime.”

Japan Oil Gas, and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) successfully finished a deep-sea mining trial in Japanese waters three years ago. “We are concerned about possible delay of these projects in this year due to the Covid-19 pandemic“ says a representative from JOGMEC. Worldwide economic downturn may depress future metal prices and discourage future investment for deep sea-mining. “The Government continues implementing the projects, which would build incentive to encourage investment for deep sea mining by the private sector” they added.

Professor Tetsuo Yamazaki of the Osaka Prefecture University, published “Past, Present and Future of Deep Sea Mining“. He explained that from the lessons learned from the pandemic, global industries may want to create a kind of separated or independent supply and consumption mechanism. “It means additional several years will be necessary to recover the metal demands. The total years, about 10 years, will be the delay time to realize deep-sea mining.“ warns Yamazaki. When it comes to Japan, Yamazaki says that originally both the Japanese Government and contractors did not rush to realize deep-sea mining. “While we, Japan, can get on-land resources from over-seas with reasonable prices, we had better to use them for our industries and society.“ Under the economic stagnation caused by the pandemic, the fundamental position is the same. “If we cannot get metals with reasonable prices from deep-sea mining we need not to hurry. We had better to develop some innovative technologies at first then start deep-sea mining by applying the technologies.“adds Yamazaki. “In my opinion we had better to select the deep-sea mining near future”.

Technological development is extremely important for the deep-sea mining industry, but also for the health of our ocean. Jon Machin is the Head of Offshore Engineering at DeepGreen. “Currently the pandemic is creating a fairly severe negative impact on the industry,” Machin says. He explains that many projects rely on the complex and sophisticated interaction of an extended supply chain, international in nature, which includes a multitude of different technology providers working together. Even if only a small number of links in such a supply chain go down, overall project deliveries can be affected. “We are currently seeing this phenomenon on quite a large scale and its definitely reducing the industry’s ability to execute and deliver. Furthermore, many of our projects take place from specialist vessels at sea. Transport and port entry restrictions, and personnel isolation requirements are currently restricting marine operations in many parts of the world.” Machin says that existential problems to the planet which marine technology can help solve have definitely been further exposed by the current pandemic; Global warming, continued destruction of land resources and habitats, and security of supply of critical minerals, for example, are all big challenges in which a thriving marine technology sector plays a role in finding solutions, both on a national and global level.

“We will encourage both our nation state champions, and global institutions, to strongly recognize and support the pioneering work of the marine technology industry” concludes Machin.

The deep-sea mining industry needs science and scientists, research is necessary do get the job done, but also it it crucial to protect the ocean and the biodiversity from negative impacts. Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR) collaborates with independent scientists for their Mining Impact Project.

Kris Van Nijen, the managing director of GSR says that so far they haven’t experienced delays to their program as a result of COVID-19. “Obviously we’re concerned first and foremost of the health and wellbeing of our people and most are now working from home. In terms of our progress, we’re focused on the next milestone, which is to test our prototype nodule collector, Patania II, and planning for our next expedition to the CCZ. That expedition will be monitored by dozens of independent scientists under the auspices of JPIO II. The results will allow us to better predict impacts in the future and will allow us to refine our engineering designs, if needed.”

He hopes that once the pandemic is over the marine science community, industry, governments and NGOs can come together to tackle climate change, which remains the greatest threat to the future health of our planet.

Daniel Jones at the Ocean Biogeochemistry and Ecosystems Research Group, National Oceanography Center, Southampton is one author of the study “Biological effects 26 years after simulated deep sea mining“. He said that the global response to coronavirus is leading to challenges for deep sea research. According to Jones, restrictions are leading to delays in field campaigns, difficulties in lab work and inevitable delays in the production of some important data. “Clearly all efforts to protect people’s health and save lives are paramount, and much deep-sea work is still being done“ says Jones. But Jones adds that many in the research community are using their available time for analyzing exciting data and documenting new results.

Conn Nugent says that probably there will be a reduction of new ship-based research for the next few months, but expects a quick return and even expansion of on-water research. He said that most ocean science is conducted by governments or government-sponsored entities of relatively wealthy countries, and those governments are almost all committed to financial pump-priming through increased government outlays and that the UN Decade of Ocean Science campaign will help as well.

Kristina M. Gjerde is a High Seas Policy Advisor for the International Union for Conservation of Nature Global Marine and Polar Program. She explained how the pandemic might impact research and regulations which depends on how long the crisis lasts. “What I have heard is that many research cruises to the deep sea are being cancelled. I assume this would apply to the contractors’ cruises as well” she says. There are significant baseline assessment requirements that the contractors still need to address so this will delay progress. This year we can expect many postponed meetings. Gjerde says that it is likely but not certain that the International Seabed Authority will postpone its next meeting in July. Since there is a still much work to do on the draft regulations, this would set back progress by at least half a year. A workshop on Regional Environmental Management Plans which was scheduled for June in St. Petersburg, Russia has been postponed. The draft exploitation regulations still have some ways to go and many are calling for the developing of environmental Standards and Guidelines as well as Regional Environmental Management Plans before the regulations are adopted. “As we are already seeing here in Boston, investors are becoming more risk averse and may be unwilling to continue to invest in an already politically, technologically, and environmentally challenging industry” adds Gjerde. She suggests the best possible option to protect the time, research, and money already invested in deep seabed mining would be for the contractors to consolidate efforts and focus much more on environmental and technological needs; there are still too many unanswered questions and concerns about the environmental impact as well as whether there will be any long term financial benefits to humanity.

In 2011 the Joint Programming Initiative Healthy and Productive Seas and Oceans (JPI Oceans) was established as an intergovernmental platform open to all EU Member States and Associated Countries who invest in marine and marine research, with a focus on collaboration between EU Member States, Associated Countries and worldwide partners. Willem De Moor is an advisor at JPI Oceans. He reports that they are currently in dialogue with the international team of scientists who is working on the MiningImpact project to ensure flexibility and discuss contingency planning. “Together with the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), the project is planning an additional research cruise which among others will independently study in real time the environmental impact of a manganese nodule collector pre-prototype test conducted by the Belgian company DEME-GSR. The expedition is scheduled to take place from mid-October to the end of November 2020 and will visit the Belgian and the German contract areas of the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean,” says De Moor. Currently they still assume that the research cruise can take place, but they will be discussing alternative options if that proves to be necessary. When it comes to challenges, De Moor says that they are trying to maintain their local community services and their own development in the context of the upcoming Horizon Europe research and innovation framework programme of the European Commission and they have postponed proposal submission deadlines for three calls for research proposals giving research teams more time to reorganize and adapt. “In these circumstances, it is our priority to meet the needs of the researchers who are funded under the framework of JPI Oceans or are in the process of applying for funding.” adds De Moor.

“Based on the past experience,” says historian Ole Sparenberg, “I would advise decision makers to take a long-term perspective”. Policy makers in the past were fixated on contemporary affairs. After the 1973 oil-price shock, policy makers feared similar boycotts and price gouging on the metal market. In 2010, Spalenberg explains, China temporarily halted the export of Rare Earth Elements (REE) to Japan sparking a global panic about REE-supply. In both cases, there were dramatic increases in metal prices and deep-sea mining was floated as remedy to the crises, as it promised higher supply and increased security of supply, which failed to materialize.

Jon Machin, however, is confident in the resilience of the industry, highlighting that the trajectory of technology, particularly marine technology, has always been to overcome natural challenges and ultimately improve both the environment and overall quality of life.

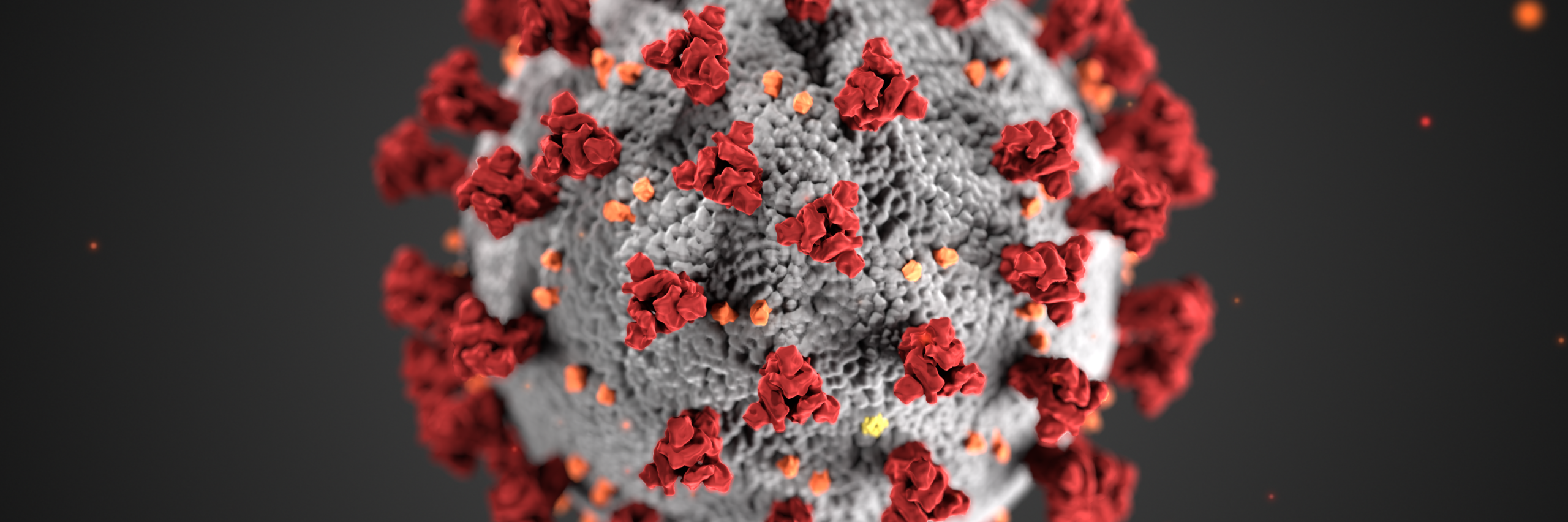

Featured image: Covid-19 via US State Department.