Maria Bolevich for DSM Observer

Stakeholders and policymakers rightly focus on the impacts that accessing ore from the bottom of the ocean will have on the marine environment, mineral supply chains, and next-generation technologies, but the consequences of this emerging industry will have social impacts that reach far beyond the seafloor. We contacted several individuals across the deep-sea mining community to talk about the potential social, scientific, and geopolitical impacts that could result from the industry’s development.

“If 2020 has shown us anything,” argues Gerard Barron, CEO of DeepGreen, “it is that female leadership has provided a steady hand on the tiller at a time of unprecedented upheaval; science, technology and innovation all have a key role to play in addressing global challenges such as poverty eradication, economic and social protection and the environment and women in leadership will play a vital role in meeting these objectives.”

“DeepGreen has already benefited immensely from the scientific expertise of female developing-state nationals in our deep-sea science programs which remain ongoing; we are also incredibly lucky to have Christina Pome’e, our Country Manager for the Kingdom of Tonga, who brings extensive experience in deep-ocean research and the sustainable development of this Common Heritage resource” says Barron who adds that bridging the gender gap in marine scientific research is a key focus of the International Seabed Authority and it has established a vision to provide women, particularly those from developing states, access to innovative capacity development programs to increase participation rates well above their current 38%.

“Our latest environmental research campaign, which set sail from San Diego on October22 and will be at sea for six weeks, counts 12 female scientists on board. All these independent researchers are leaders in their field and will make invaluable contributions to the development of deep-ocean science,” says Barron.

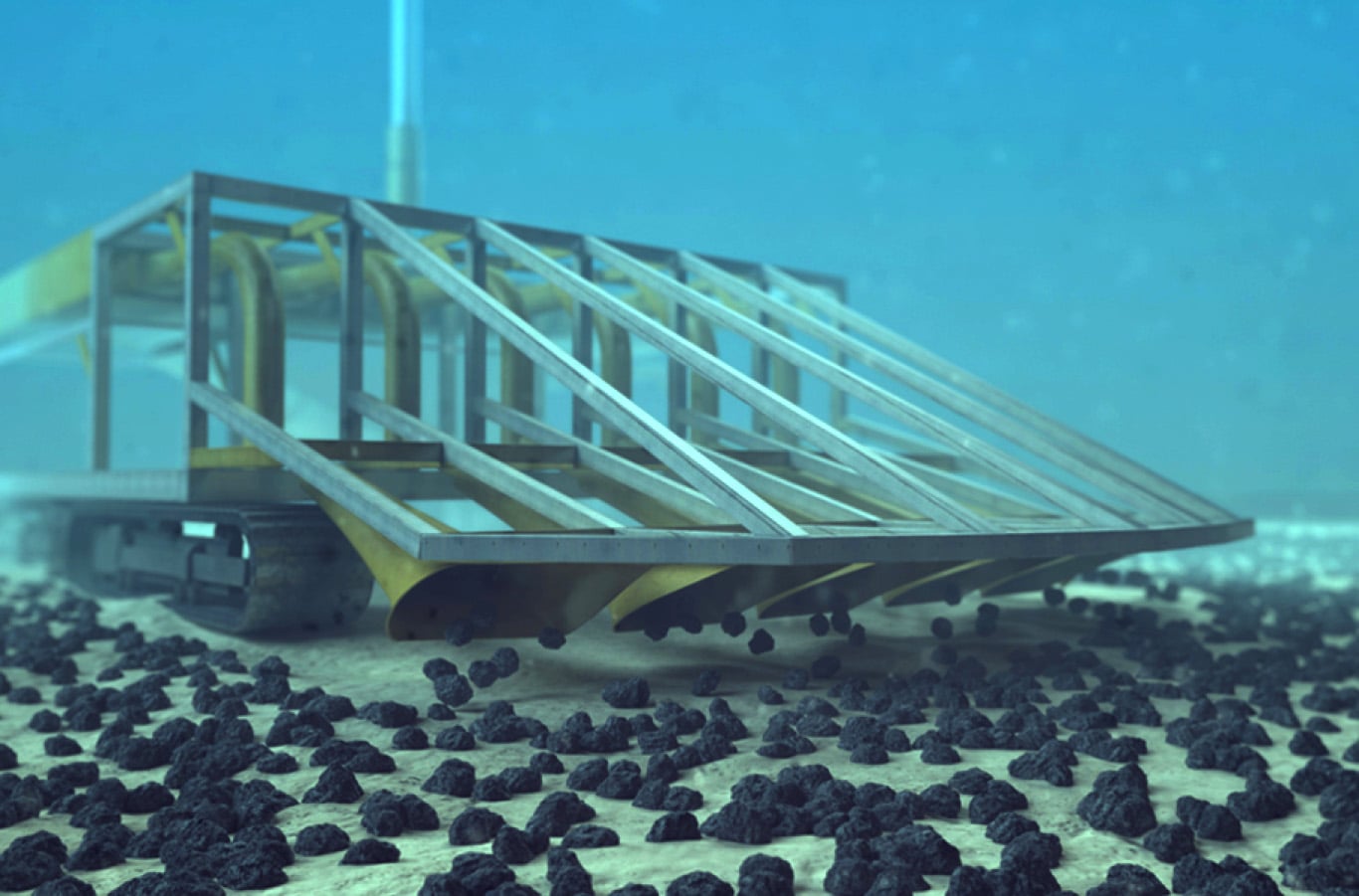

DeepGreen is also thinking about their corporate ecological footprint. Barron says that with approximately 250 people working on the project at DeepGreen and their partners, their current impact is small and dominated by the emissions from their offshore exploration campaigns, where their partner, Maersk, runs a tight ship. “These impacts are trivial compared to the contribution we will make by decarbonizing and detoxifying metal production. Some of our initiatives that will make a real difference include: our investments in developing a hydraulic nodule pickup that would cause as little sediment disturbance as possible; developing and testing a zero-waste processing flow sheet; and a global plant-siting study based on access to renewable power. We are also experimenting with carbon-neutral and even carbon-negative replacements for coal-based reductants to further reduce our emissions footprint.” says Barron.

DeepGreen is also working to advance scientific progress through its research partnerships. They have already compiled an extensive library of deep-sea biological samples and they expect to expand this collection. “We’re inviting researchers interested in unlocking the potential for scientific discovery of this growing sample collection to get in touch. We already have one academic partnership in place purely for scientific characterization of the genetic resource potential of our ever-expanding sample library. Of course, we welcome further collaborations.” says Barron.

Barron adds that Deep Green has partnered with the world’s leading academic and research institutions to establish biological baselines and build a holistic understanding of the water column, from seabed to surface. “This program involves over 100 independent researchers and includes dozens of discrete studies of pelagic and benthic biology, bathymetry and ecosystem function of the CCZ as part of our wider Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. These researchers will have carte blanche to publish whatever they find and we expect a proliferation of peer-reviewed papers in the coming years. All we can do is be transparent about what we do and why we do it. And be true to our commitment to leave nodules alone if we find something that would disprove our current hypothesis.”

And Barron understands the historic distrust of extractive industries by NGOs and environmental groups. “We can learn from past mistakes and invest time and resources into getting this new industry right. NGOs genuinely interested in the best planetary outcomes can and should play a critical role in this process – we invite them to keep us honest. We have actively sought inputs from them in the past and our doors remain wide open.”

Deep-sea mining is often presented in contrast to artisanal cobalt mining, a process that is rife with environmental and human rights issues, in particular, child labor. “What we can guarantee is that no child labor or human rights abuses will be involved in metal production from poly metallic nodules. How this could impact child labor on land will depend upon what share of metal demand will be supplied from nodules vs. land ores. It’s ridiculous to suggest that DSM is the only way to stop child labor,” says Barron. He explains that local interventions should and are being pursued by current participants in the electric vehicle value chain. “But we must also recognize that child labor is a complex social and economic issue, with no easy solutions. Eliminating demand for cobalt won’t solve the economic problems of the families who send their kids into toxic cobalt mines today… Fortunately,” concludes Barron,“ a new generation of environmental leaders and NGOs interested in solving real-world problems is emerging.”

As the first 21st century commercial industry to focus on resources in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, deep-sea mining occupies a unique geopolitical role. Simon Dalby, professor of Geography and Environmental Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, explains that decades of deep-sea mining promises have yet to yield the predicted geopolitical tensions. “The arguments back then were that the rich countries that had the necessary technology would effectively exclude developing countries from the benefits gained by using the minerals.” says Dalby. But, Dalby explains, that issue is not unique to deep-sea mining.

“While exclusive economic zones have proliferated and facilitate offshore oil and gas drilling in particular, which make climate change worse by extending the supply of fossil fuels, this has caused tensions where claims overlap .”he says. According to Darby, the Norwegians and Russians solved this problem in the Barents Sea by splitting the difference in their overlapping claims. “It’s not clear how this will play with the Malvinas/Falklands or in the South China Sea, or for that matter in the Eastern Mediterranean either. What matters in terms of climate change is preventing the exploitation of these resources in the first place to reduce the use of fossil fuels. But this isn’t what the original concerns about minerals on the seabed were about.”

While the promise of deep-sea mining remains rooted in finding new, more sustainable sources for the resources necessary to wean the world off of fossil fuels, the downstream impacts of this emergent industry will be felt in diverse and unexpected ways.

“Collecting poly metallic nodules won’t guarantee world peace or sustainable world but it can certainly make a globally significant contribution to compressing the environmental and social costs of the clean energy transition while offering some of the most climate vulnerable states, which have historically occupied a peripheral position in the global economy, a chance to participate in and benefit from resource development in international waters,” says Barron.

Featured image: researchers watch the sunset aboard the RV James Cook. Photo by A. Thaler.