New animal species that are genuinely new to science are remarkably rare. The modern process of discovering and describing a new species, particularly animals, usually follows a pattern of creating more and more nuanced distinctions between already known groups. “New to science” rarely means “never before observed”. In other words, when we find a new fish species, it is usually not an animal that has never been seen, but rather a known animal for whom new information points towards a clear delineation between its closest relatives, with which it was previously grouped.

What makes deep-sea exploration so exciting is that, unlike with shallow water and terrestrial ecosystems, new species are frequently totally new. When a new animal is found in the deep ocean, it is more often than not the first time human eyes have ever observed that animal.

For all its flaws, 2020 was a good year for discovering new species in the deep ocean.

A single expedition by scientists from the Western Australian Museum discovered at least 30 new species, including a giant hydroid and a siphonophore, which, at 47 meters, may be the longest animal ever recorded, dwarfing the blue whale by over 15 meters.

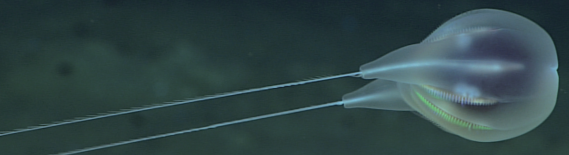

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, a team from NOAA fisheries discovered a new species of comb jelly off the coast of Puerto Rico. Though first observed in 2015, it took another five years for this weird gelatinous blob to be formally described.

2021 is already shaping up to be a banner year for discovery. Just this month, a new copepod species, Enhydrosoma texana nov. sp. was described from the deep Gulf of Mexico. While this genus is common in shallow waters, this new species, found at over 2000 meter depth, is the deepest dwelling member of its genus. On a less exciting note, a new species of boring bivalve has been described from the waters around Australia. The deep-sea wood-boring Abitoconus investigatoris is the first Xylophaga to be described from Australian waters in over 60 years.

Closer to home for the deep-sea mining community, a new species of stalked barnacle was discovered from hydrothermal vents in the Mariana back-arc basin. Vulcanolepas verenae is closely related to other stalked barnacles found in the southwest Pacific, including Solwara I, but this is the first report of barnacles from this genus in the northern hemisphere. Unusual for barnacles, but not uncommon for the fauna which surround hydrothermal vents, Vulcanolepas are farmers–they culture and consume filamentous bacteria which may derive nutrition from the chemical energy of the vent plume.

The new stalked barnacle is named for Canadian deep-sea researcher Dr. Verena Tunnicliffe.

While new species from the deep sea are frequently truly new, shallow water species that have never before been observed are still rare. Last month a team from Mexico described what they believe to be a new species of beaked whale, identified from three individuals and from acoustic signatures that point towards a previously unobserved species. Though still preliminary, if confirmed, this would be a significant discovery.