Andrew Thaler for the DSM Observer

While environmental impacts dominate the public discussion surrounding deep-sea mining, another highly contentious barrier to the implementation of a deep-sea mining code carries equal, if not greater weight within the International Seabed Authority. The financial regime, a novel payment structure which establishes the mechanism by which proceeds generated from the mining of seabed resources held in trust for the “Good of Mankind” translates into how actually distributing wealth from the bottom of the sea to member states, contractors, and the Secretariat, works in practice. While negotiating the environmental regulations that dictate how deep-sea mining progresses is a complex process involving a diverse group of global stakeholders, there are models from similar industries and ventures to draw from. The financial regime is a monumental undertaking which has no comparable precedent among any other industry.

Throughout the first part of the 27th Session of the International Seabed Authority, informal working groups to discuss the financial model and payment regime dominated the first week of the meeting. Despite long and detailed discussions, the assembled delegates ended the conference no closer to finding resolution than when they had begun. As negotiations continue through the interim, it will likely fall to the Summer council meeting to begin finding compromise among the various stakeholders and their often conflicting financial interests.

At the core of the discussion is the practical mechanism of the financial model, how fees are assessed and when payments are required. That mechanism has been narrowed to two variables – a royalty rate based on either ad valorem (the estimated value of the ore) or realized profit and a pay schedule that may be either fixed or variable.

For contractors and investors, profit-based royalties are appealing because they better account for variability in global markets and production capabilities. But, during the discussion, many delegates noted that profit-based royalties have several downsides. They are more vulnerable to manipulation and a contractor that is expanding its capacities could structure their growth in such a way as to never generate a profit. The International Seabed Authority only has regulatory authority over minerals when they are removed from the seafloor. Once the ore is mined and transported to shore, it no longer falls within the Authority’s aegis. Thus, numerous delegations argued that the only reasonable moment to assess value is at the point of extraction, based on the market value of the raw ore, rather than at the point of sale.

The pay schedule also has a significant impact on contractor’s ability to sustain their operations. A fixed fee guarantees that early into the commercialization of deep-sea mining, the ISA will begin generating revenue that will allow them to continue the work of monitoring and overseeing the developing industry, and member states will finally begin seeing payouts after decades of negotiation. But a fixed fee places more burdens on early production, when a contractor carries the greatest financial risk.

The discussion led to many delegations highlighting the idea of fairness, acknowledging that if contractors and sponsoring states were unable to become financially sustainable, no one would be able to derive profit from deep-sea mining. But that idea of fairness also extends to member states which do not sponsor mining contractors, member states which are bracing to receive the bulk of the environmental impacts from mining, and member states which have terrestrial mining industries which could be threatened by the development of deep-sea mining.

Also up for consideration was the administrative complexity of the payment regime. The ISA is empowered to collect fees based on the final payment regime, but how it determines those fees can be a complicated and controversial process. Several delegations argued that an ad valorem payment regime where the value of ore is determined based on prevailing metal prices at the point of extraction is a simpler and more efficient way to determine value. A profit-based regime would require extensive analysis and auditing of contractors’ financial records in order to assure stakeholders that fees were being collected fairly.

How and when payments are collected by the ISA has a substantial impact on all downstream operations. Ultimately, the ISA will not only fund itself through payments from contractors, but also maintain several development and management funds which are essential to the safe and effective operation of the Enterprise.

A particularly pressing issue during the informal working groups was how the Environmental Fund would be established. Several delegations noted that the industry is extremely volatile, and there’s no guarantee that a contractor that initiates commercial mining will still be solvent by the time environmental remediation is needed, noting that The Metals Company lost a significant amount of its value over the last year and past contractors have already gone bankrupt. With a 30-year horizon for the life of a deep seabed mine, both NGOs and member states argued that contractors should be required to pre-fund the Environmental Fund, creating an additional financial burden on the contractors before any ore is raised from the seafloor. “For us, the impact of deep-sea mining is real. It is not a hypothesis,” stated the delegation from Fiji, emphasizing the fact that Pacific island nations will be the first to feel any environmental impacts from the development of the industry in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone.

Among other significant interventions, South Africa took the floor to remind the council that the current financial model only looks at the values of cobalt, nickel, and copper in polymetallic nodules, but that those are not the only economically valuable metals and that deep-sea mining will also impact the world’s manganese supply. South Africa is currently the world’s largest producer of manganese. Germany also intervened to emphasize that there were still many external costs, including the environment, that were not yet included in the models. They recommended a study on external costes, as well as supporting incentives for good behavior among the contractors.

Ultimately, the negotiation of payment regimes comes down to trust, transparency, and accountability, and comments at this meeting reflected a greater degree of skepticism and distrust towards contractors and the secretariat than in past meetings. There was strong resistance to committing to any single point of discussion, with many delegations echoing the same sentiment “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.”

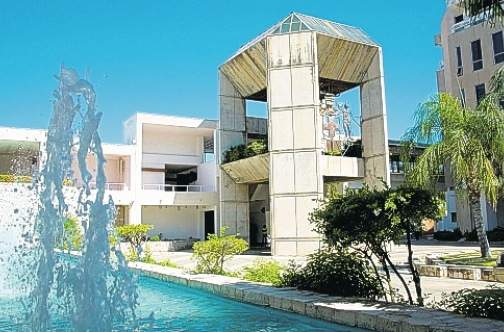

Featured Image: Skutterudite, a cobalt and nickel-bearing ore, from Ontario, Canada by James St. John.