Andrew Thaler for DSM Observer

The Council of the International Seabed Authority gathered for a rare third meeting in Kingston, Jamaica this November to continue hammering out details of the Deep-sea Mining Code ahead of the July 2023 deadline. As has become customary over the last year, negotiations began with condemnations of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, followed by a walkout of member states during the Russian Federation’s intervention to defend its position and urge delegations to keep politics out of this UN negotiation.

Central to this negotiation is the invocation of the 2-year-trigger, which imposed a deadline of July 2023 on the completion of the Mining Code. When the ISA fails to finalize a Mining Code by that date, an outcome which, procedurally, is inevitable, any submitted plan of works must be considered by the Authority on its own merit and on any prevailing standards and guidelines. However, many member states asserted that, as they believed that a finalized Mining Code is essential to any review process, they would be unwilling to approve any plan of work prior to the adoption of the Mining Code.

The delegation from Spain asserted that “the two-year rule does not matter if we do not have adequate environmental regulations in place.” Australia reiterated its position that “no exploitation should be finally approved until the regulatory framework is in place.”

But not all member states were in agreement with that sentiment. The delegation from India stated that “as we are dealing with commercial exploitation of the common heritage of humankind we should not be in a hurry, or to be seen to be in a hurry, however the 2-year clause did push us to work in this area. We should try to reach consensus and conciliation which is preferred under the convention. India wishes to try to proceed by 2023.”

The delegation from Germany took an opportunity on the first day to express that “the current knowledge and available science is insufficient to approve deep seabed mining until further notice,” and called for a strict application of the precautionary approach, echoing support for Costa Rica’s proposal of a precautionary pause in the commercialization of deep-sea mining. Spain, Panama, and several other member states also voiced support for this precautionary pause.

Perhaps the most significant intervention of the session came from France, who clarified President Macron’s statement at the COP27 meeting in Sharm El Sheikh regarding France’s position on a deep-sea mining ban. “Today it does not seem reasonable to hastily launch a new project, that of deep seabed mining, the environmental impacts of which are not yet known and may be significant for such ancient ecosystems which have a very delicate equilibrium.” The French delegation went on to explain that “currently, given the absence of scientific knowledge, we cannot today guarantee that mining mineral resources in the Area would not cause irreversible damage to the seabed and its biodiversity. That is why France, which has the second-largest exclusive economic zone, calls on its partners to make the same commitment to preserve this highly valuable marine ecosystem. Our precautionary principle must translate into tangible action, for the benefit of all humankind.”

Drawing from the long and complicated history of the ISA, the French delegation explained that the challenges facing the world in the closing decade of the 20th century were substantively different from those that nations face today. “When the ISA was created by the Montego Bay Convention, almost 30 years ago now, the challenges that we face today, the urgency of climate action and the collapse of biodiversity and its ecosystem services, were not the same. Our collective work must fully incorporate these challenges today. We must therefore allocate the time needed, which will be much more than initially envisaged, without any industrial or financial pressure, and without letting this work be guided by concerns other than those that are the fruit of knowledge and the need to protect marine ecosystems. As environmental imbalances challenge the living conditions of humankind, it would be dangerous to act with haste, endangering these ecosystems that could be sources of solutions and resilience in the future.”

The French delegation concluded by reiterating their position, “as of now, we are therefore joining all the States that are truly concerned by the protection of this common heritage that is the marine environment and its biodiversity, and who have recently expressed in various ways their concerns over deep seabed mining. In this forum, we are of course open to constructive dialogue with all of your governments and the ISA so that we can make inclusive progress on the knowledge of the seabed for the good of humankind.”

While the French Intervention was met with praise from NGOs and many member states, others expressed their disappointment with this hardline stance against the developing industry.

“A prohibition against deep-sea mining seems an unfortunate departure from our collective endeavors to complete the mining code and thus achieve our legal obligations under UNCLOS,” stated the delegation from Norway. “Norway shares many of the concerns raised and believes in the objective that mining should not occur without the complete regulations in place. In our view, the best way to achieve this is to continue and to redouble our efforts to finish these regulations.” Singapore concurred, stating that they could not support such a ban on the development of deep-sea mining.

Several member states raised the issue of France’s ISA lease blocks and whether the country would surrender those leases back to the ISA. Under UNCLOS, lease blocks are issued to member-state-sponsored contractors on the condition that they make progress towards commercialization of the industry. This rule exists to prevent oppositional member states from locking up key regions of the seabed to block mining progress.

In seeming deference to a prevailing feeling of frustration with the looming deadline, the Republic of Nauru, who had initiated the two-year countdown, stated that they would not submit an application of a plan of work in July 2023. “We do not wish to prejudice the adoption of regulations by that deadline,” stated the delegation. With no plan of work for the LTC to consider in the absence of a Mining Code, this effectively renders the July 2023 deadline moot. “Like the UK and others, we remain optimistic that together we can make significant progress between now and July 2023 and feel confident that by the end of July session next year, we will be significantly advanced.”

Nauru’s intervention helped calm concerns over the looming deadline. An abbreviated “what if” session to assess what would happen if the Mining Code were not in place ahead of the first plan of work resulted in few discussions. Under the current schedule for the 28th session of the ISA, the organs of the Authority empowered to approve the Mining Code won’t convene again until after that deadline is past.

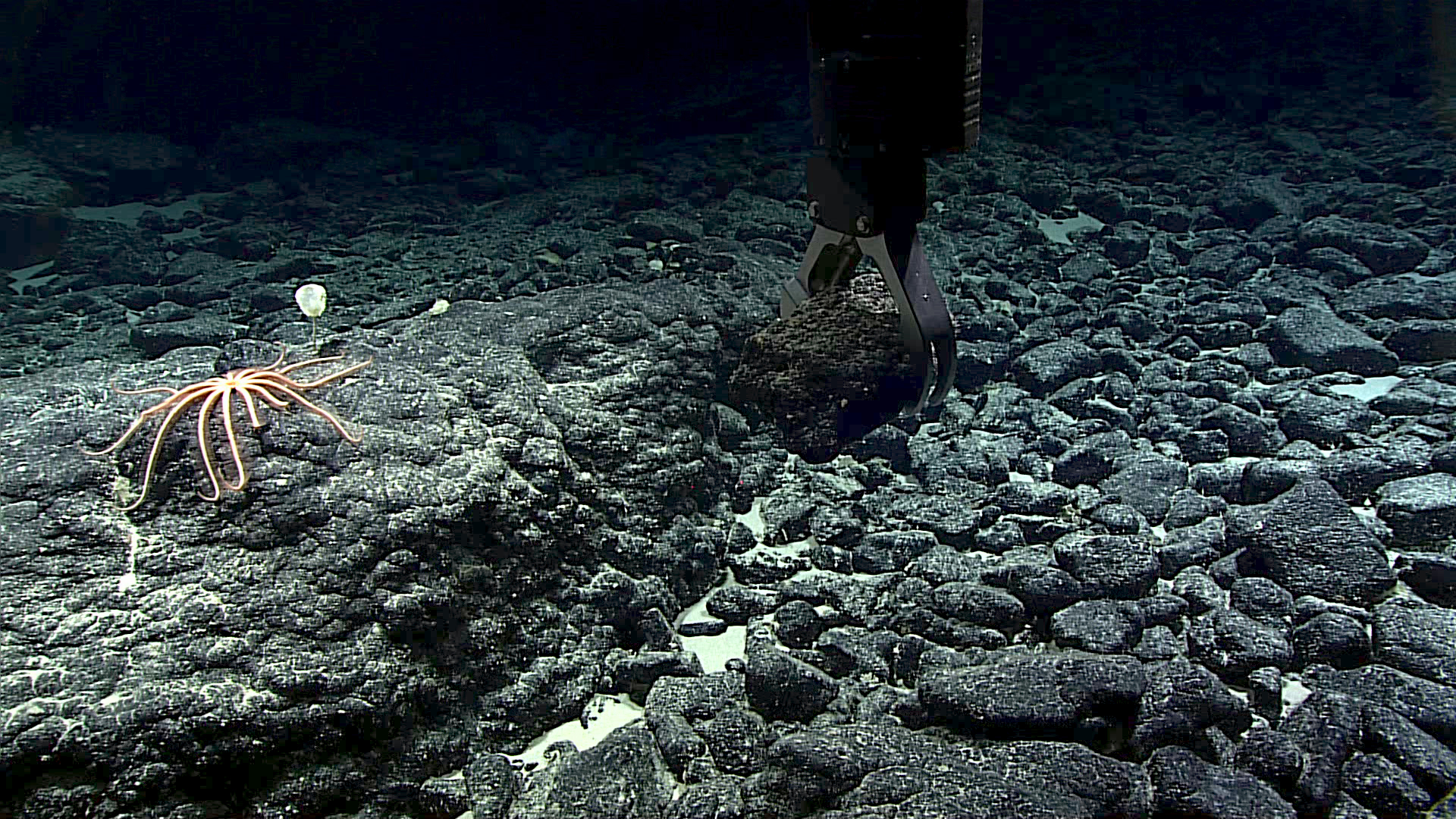

Though the bulk of the meeting was dedicated to making substantive progress on the Mining Code, other issues also loomed over the meeting. The Metals Company nodule collector test in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, which had been met with protest from observers and some member states over the environmental impact assessment process, was underway. Several delegations argued for clearer and more transparent requirements for stakeholder review prior to the approval of future tests.

The financial regime remains very much under contentious discussion. Royalty rates for profits from deep-sea minerals will likely remain a challenging point of negotiation well beyond the 28th session. “You can’t just mine away the minerals which are the common heritage of mankind, and expect that we will allow you to just pay 2% and then off you go,” intervened the delegation from South Africa.

“Our primary objective remains a timely adoption of exploitation regulations, standards and guidelines that provide for strict environmental protection,” stated the delegation from Germany, emphasizing that “the commencement of deep-sea mining is the single most important decision this Authority has to take, and must concern a majority of the Council.”