Maria Bolevich for DSM Observer

Dr. Malcolm R. Clark is a principal scientist at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in Wellington, New Zealand, he began his career in the 1980s. “My career started with fisheries stock assessment, and evolved through studying the diversity of deep-sea life and how it is impacted by human activities, to trying to translate science into effective management,” says Clark. “As such, it is always a challenging and changing job, but hugely satisfying when it helps result in balancing exploitation with environmental conservation.”

Dr. Clark is one of the authors of the book Biological Sampling in the Deep Sea, which attempts to standardize sampling approaches and methods across scientific programs and countries. “A lot of data were being collected by countries and researchers, but in ways they couldn’t be combined in larger-scale analyses. The old saying that ‘the total is greater than the sum of its parts’ is true when we can pool research over larger spatial and temporal scales, and start to understand, not just describe, how marine systems are structured and function.”

Dr. Clark is a member of the Legal and Technical Commission, an organ of the International Seabed Authority and is the lead author of the study “Environmental impact assessment (EIA) for deep sea mining”. In an interview with the Deep-sea Mining Observer, he answered a number of questions about the EIA process, as well as its challenges and shortcomings.

DSMO: You are a member of the Legal and Technical Commission, can you please explain the importance of the Commission, your duties, and what cooperation between the ISA and the Commission looks like?

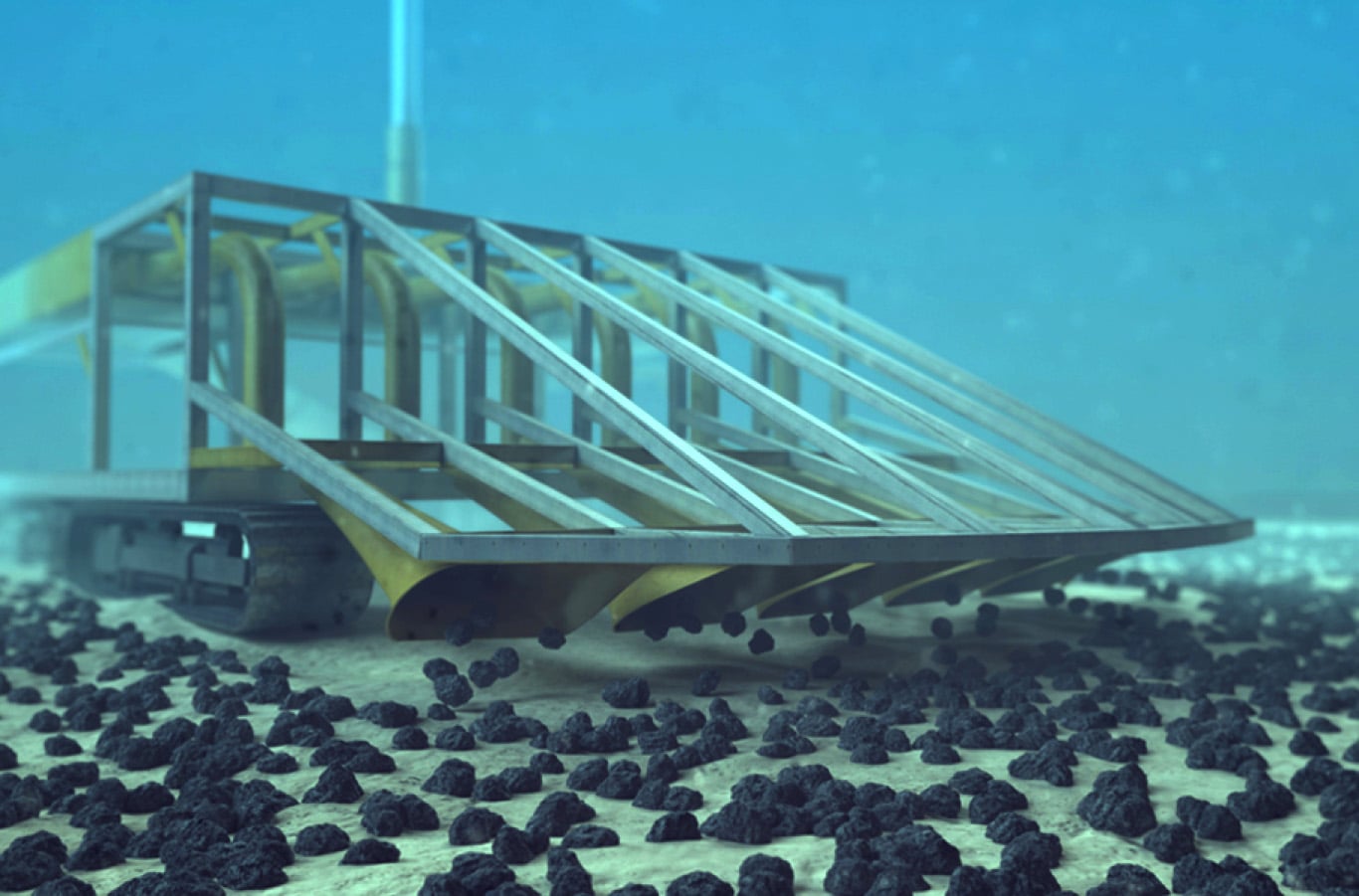

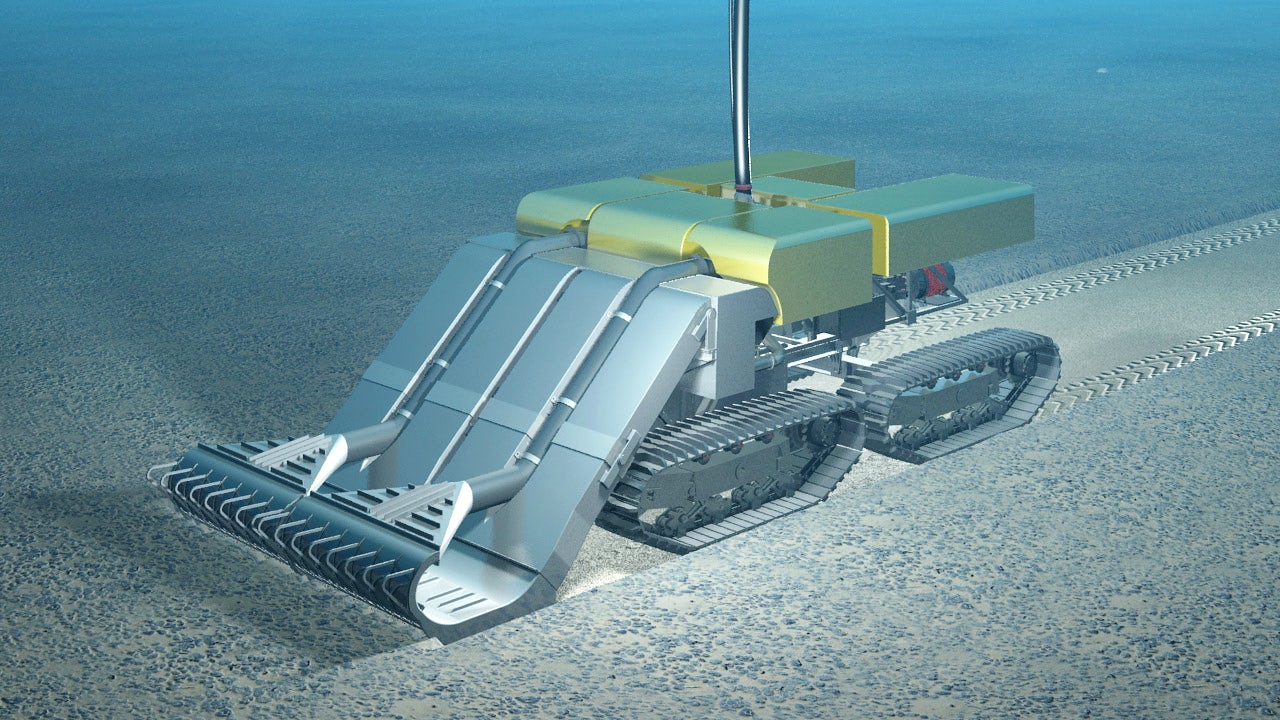

CLARK: Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) the International Seabed Authority was established, which is a United Nations organization that is responsible for managing mining activities in the High Seas. The Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) is part of the ISA and its job is to support the ISA Assembly and Council in developing policy and operational regulations for exploration and exploitation of non-living marine resources (such as manganese nodules, seafloor massive sulphides and cobalt crusts, which are the main resources that contain commercial minerals). It currently comprises 30 people nominated to the Commission as independent experts across multiple disciplines that include international law, resource evaluation and technology, and environmental science. Tasks include reviewing applications for plans of work, supervision of exploration or mining activities, and assessment of the environmental impact of such activities. So in the context of environmental management, the LTC has a major role to play in advising the ISA Council and Assembly on issues associated with exploration and exploitation activities. As an example, issues currently being addressed by the LTC include the process and content of EIAs, Environmental Management and Monitoring Plans (EMMPs), Closure plans (post mining), and the production of standards and guidelines to help contractors and the ISA be consistent in a variety of tasks needed under developing regulations.

DSMO: You are the leading author of the study “Environmental Impact Assessment for Deep Sea Mining: Can we improve their future effectiveness?“, how was the study conceived and what was the most difficult part for you and your team? What is your opinion about deep-sea mining?

CLARK: Deep-sea mining is a new industry. It has not yet started, yet a large amount of exploration is being undertaken to evaluate the commercial viability of mining, as well as to assess the environmental impacts. However, EIA in the deep sea is potentially a very difficult and expensive process. Hence, thinking about what is needed to produce a good assessment has to happen early on during exploration. Hence the motivation for this study was to try and highlight some of the key deficiencies in EIAs that need to be avoided if they are to be successful.

The most difficult part of such a study is avoiding creating a long list of research problems, which although this might be needed, what is important going forward is to focus on the major issues that need to be addressed and resolved. In the deep sea there are important practical limitations, and so any advice needs to be realistic and feasible. And this can be challenging when we are likely faced as scientists with insufficient information to be sure about mining impacts.

Deep-sea mining is a complex issue, and ultimately will depend upon decisions made by Society/Countries about what human needs are in terms of what mining deep-sea resources can provide, and whether environmental impacts (and there will be impact) are acceptable. Scientists are part of the mix of interests involved. As a scientist, my key concern is, if deep-sea mining goes ahead, that its operation and management are based on best scientific information to ensure environmental sustainability.

DSMO: What shortcomings in EIA for deep sea mining are identified and how can they be solved?

CLARK: Scientific shortcomings, based on looking at several EIAs produced for offshore mining, as well as other sectors,include inadequate baseline data, insufficient detail of the mining operation, insufficient synthesis of data and the ecosystem approach, poor assessment and consideration of uncertainty, inadequate assessment of indirect impacts, inadequate treatment of cumulative impacts, insufficient risk assessment, and consideration of linkages between EIA and other management plans. This list might seem huge, but it boils down to knowing enough about the current state and status of the environment before anything happens, and understanding well enough the impacts that are going to be caused by mining. Only then can options be determined for reducing impact to an acceptable level, and then applying methods to monitor the success of the operation in achieving that reduction. Uncertainty in both the environment (especially its variability) and science are major challenges for an EIA, yet are important for applying the precautionary principle as potential mining develops.

DSMO: In your opinion, are scientists interested in cooperation when it comes to EIA for deep sea mining?

CLARK: I am not aware of any scientist that is not interested in cooperation when it comes to EIA. There are already partnerships developing between scientific disciplines, and between contractors and scientific agencies-these are both logical and necessary. I think there is a clear realization that if deep-sea mining is to proceed, then science is an integral part of it, and that a successful EIA involves cooperation between many sectors and disciplines. Understanding the structure and function of the existing ecosystem, the nature and extent of impacts, and what is needed for appropriate management, are key elements of an EIA, and that requires a high degree of collaboration and cooperation.

DSMO: Public participation is very important. How can the media help and, on the other side, do you think that disinformation about deep-sea mining can affect public opinion? How can we be sure that public knowledge and awareness is well-informed?

CLARK: The media has an important role to play in promoting the dissemination of accurate information, and this links strongly with the need for a transparent process as potential mining develops. A number of countries have environmental regulations that require all environmental information is publicly available. This can then ensure that “fake news“ is identified and discredited if necessary. Formal scientific publication of environmental studies (with peer-review) is becoming standard in industry, and is also being encouraged by many companies involved in exploration for deep-sea minerals. So there is a natural maturation of industry to be environmentally responsible, and when combined with independent science, and an open and transparent management process (such as proposed by the ISA for public posting and review of all EIAs, EMMPs etc) this will improve the level of public knowledge, and confidence in utilization of what, in the High Seas, is a global resource belonging to human-kind.

DSMO: Are decision makers always interested in taking EIAs into account EIA and what is the most difficult part for scientists in situations where EIAs are not well-received?

CLARK: I have no experience with situations where decision-makers are not, by law, required to take EIA into account. The most difficult job of the scientists, but also their main responsibility, is to ensure that the quality and comprehensiveness of the EIA are as good as they possibly can be. That involves also an open and honest evaluation of important gaps and limitations in the assessment, and the degree of certainty in the results that are presented.

DSMO: As mentioned in your book “The deep sea covers over 60% of the surface of the earth, yet less than 1% has been scientifically investigated.” When we have less than 1% scientifically investigated, what crucial steps should be taken to ensure that deep-sea mining is environmentally sound?

CLARK: The lack of sampling in the deep sea, and the differences in methods and approaches applied in that “less than 1%” is a major challenge for assessing the environmental characteristics of an area, let alone knowing what the impacts on the structure or function of the ecosystem will be. This emphasizes the need to ensure all data are able to be combined, so an integrated assessment will use as much information as possible (even if it might not be enough). While an individual mining operation might be limited in its area, knowing the impacts will involve assessing how unique, or standard, the conditions and biological communities in that smaller area are, compared with the wider region. This becomes an issue of scale, both in space and in time. An important way forward is collaboration between contractors, and between scientists, undertaking the exploration studies, so that the small area is better understood in the context of the regional scale. This is happening with joint efforts by some contractors in the High Seas (for example in the Clarion Clipperton Zone) and the ISA is currently developing Regional Environmental Management. Plans for broader ocean regions than just the sites of local mining potential. This involves a wide array of scientists, NGOs, managers, policy people and the public. This combination of regional as well as local, approaches will highlight how much, or how little, is known in a region, and provide a basis for evaluating the risks of mining,whether we know enough to safely proceed or not, and if the latter what further science is needed.

DSMO: As stated in the study “there is a large gap between the best practice thinking represented in the research literature, and the application of this thought to EIA in practice.” Why and is it possible to change that?

CLARK: It is one thing to state what in theory should or could be done in an ideal world, but another thing entirely to put that into practice given the complexity of modern society. EIA is part of a process that integrates elements across science, industry, management, policy, and public disciplines. From the perspective of a scientist interested in ensuring environmentally sound management, I feel it is important that scientists realize and take into account the different viewpoints of, for example, industry, NGOs, and government policy. Scientific advice needs to be seen as realistic and practical, and very importantly needs to align with what is required for the legal and regulatory process. The EIA science needs to be targeted so it slots into the process, and becomes an integral and natural component of the regulatory system. In some cases this might require scientists to think in a less academic way, and understand more how the science needs to be applied.

DSMO: Can you explain what an EIA for deep-sea mining would look like? What are the differences between EIAs for deep sea versus terrestrial projects? Not every location and conditions are the same, but what are some general principles?

CLARK: Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is an integral component of the planning, development, and management of many human activities. Key objectives of an EIA are:

To ensure that environmental considerations are explicitly addressed and incorporated into the development decision-making process;to anticipate and avoid, minimize or offset the adverse significant biophysical, social and other relevant effects of development proposals; to protect the productivity and capacity of natural systems and the ecological processes which maintain their functions; and to promote development that generates less destruction and optimizes resource use and management opportunities.

As long as an EIA achieves these outcomes, how it gets there can vary. However, a good EIA process will always include a number of steps:Screening to establish that an EIA is necessary, and at what level.Scoping; to identify at an early stage the issues and impacts that are likely to be important, and to be emphasized in the EIA. EIA (alternatives, baseline, impact analysis, mitigation and management, evaluation of significance, preparation of EIA/EIS report); Decision-making (which includes EIA review); Follow-up and Audit (often part of an Environmental and Monitoring Management Plan).Stakeholder consultation and participation (and regular feedback cycles) are important as part of these steps to incorporate a wide range of views of interested and affected parties and public, to ensure the EIA is comprehensive, complete and has a balance between social and scientific evidence.

DSMO: “Decision-makers are working in a political environment” can that be a good thing and why?

CLARK: EIA is not just a question of science, but is part of decisions about development that need to balance a number of factors, and EIA is nested in a larger framework. Environmental plan components(EIA, EMMP, etc.) are innermost, within a regional spatial context (Strategic and Regional environmental assessments and management plans), which in turn lies within a legal and regulatory set of decision-making criteria for the region, which are themselves informed by the larger global socio-political framework of international laws and rights. This political environment can take much larger spatial and “big-picture” societal interests into account. It can be a good thing where no single sector or interest group can capture the process.

DSMO: I read in your study that the technologies are still under development, how can we be sure that we have good technology for conditions that are challenging and unfamiliar?

CLARK: Part of developing regulations for mining in the High Seas stresses the need for “Best Industry Practice” and “Best Available Technology”. This means that technologies need to be evaluated against alternative options, and associated with this is evaluation of the environmental issues caused by different technology. It is a challenge for EIAs if mining practices are not well understood. However, at the end of the day, a proposal will only be approved if the environmental impacts are acceptable within the criteria defined by the regulator. If technology is not good enough to avoid serious harm to the environment, or that can be managed to maintain ecosystem structure and function, then a proposal is unlikely to be successful.

DSMO: There is a part of the study about core principles and criteria that an EIA should account for, including being: Purposive, Rigorous, Practical, Relevant, Focused, Adaptive, Interdisciplinary, Credible, Integrated, and Systematic. Very well explained, but is it possible to achieve all those principles and criteria?

CLARK: These principles seem very ambitious and optimistic. Yet as principles, they are there to guide the content, and to have EIA practitioners think about what they have produced. The principles will be met to varying degrees, with differences for example in the quality and quantity of the information in various parts of the EIA, or its overall completeness. The principles are not contradictory, so all need to be addressed, but at present there is limited guidance on criteria to assess how well they have been met. Conditions can be very situation-specific, so it is difficult to generalize, but as said above, every EIA needs to have this sort of self-evaluation as to how well it has been done before being submitted.

DSMO: Are companies interested in polluter pays principle and in case of unprepared events who is going to pay higher price the polluter or the ecosystem? Are companies ready for that option?

CLARK: I believe most companies are realistic as to their environmental obligations. The polluter-pays principle applies in many industries. With deep-sea mining, the major impacts are most likely related to the scale of the actual operation, in terms of the area being mined, and the nature and extent of impacts being made by the various operations (physical seabed disturbance, sediment plumes etc). These are ongoing impacts that need to be managed. Catastrophic one-off accidents still need to be considered and included in any environmental management plan, but the general feeling is that it is the day-to-day operation that is of most concern. All contractors in the High Seas, and in most national jurisdictions, need to have Environmental Management Systems in place to cover both operational and unexpected “accidents“ as part of their approval conditions.

DSMO: Is EIA for deep sea mining expensive and how long will it take to finalize?

CLARK: Robust EIA in the deep-sea is expensive. Undertaking any activity in the deep sea (whether scientific research, minerals exploration) involves large ships and expensive equipment. For example, some contractors interested in manganese nodule resources have spent 15 years and many millions of dollars doing exploration in the eastern Pacific, and are probably not yet at a stage where they have sufficient data for carrying out an EIA. Other minerals are more localized and perhaps require less research-but in order to satisfy the demands of good quality data for a robust EIA, there are few short-cuts and it is both a costly and lengthy process.

The LTC will be meeting at the ISA in Jamaica next month. “During the two week period, the Commission will consider a wide range of issues, including activities of Contractors (e.g., training programs, 5-yearly reviews of their work plan), ISA data management, aspects of the draft regulations on exploitation, and a number of outstanding issues from previous meetings or arising from a meeting of the ISA Council just prior to the Commission meeting. Of particular relevance for environmental assessment is discussion and work on developing Standards and Guidelines for activities in the Area (including Environmental Impact Assessment and Environmental Management and Monitoring Plans) as well as reviewing an existing Environmental Management Plan for the Clarion Clipperton Zone (an area in the eastern Pacific Ocean where there are polymetallic nodule resources) and progress developing new Regional Environmental Management Plans. The results and recommendations from the Commission meeting will input to the main Council and Assembly meetings in July this year.”concludes Clark.

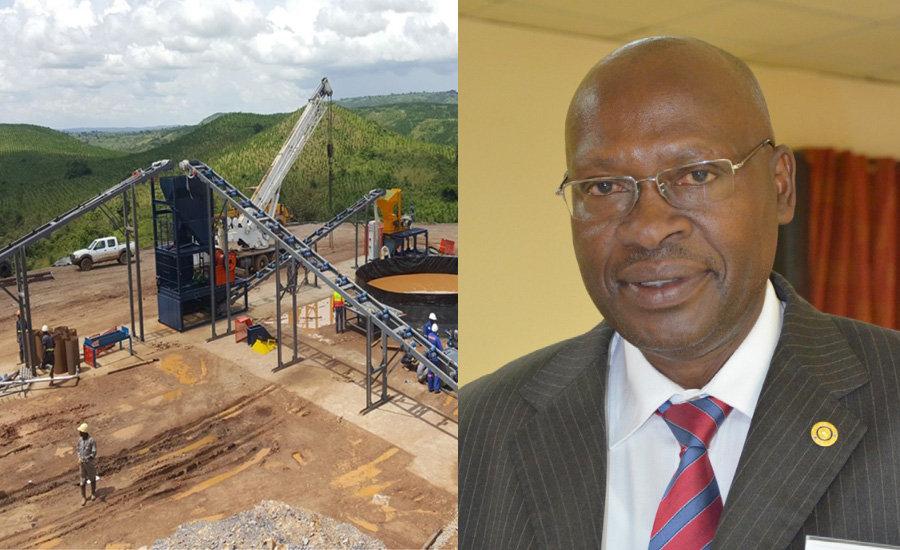

Featured Image: Dr. Clark in conversation with delegates and observers. Photo courtesy IISD/ENB.