Exploring some of the world’s most remote ocean regions is no small task, especially when the mission includes investigation of benthic habitats and features on the forefront of interest to the deep seabed mining industry. Yet a slurry of such expeditions has recently been undertaken, launching headlines around the world and contributing to our scientific understanding of the ocean floor.

In February, China embarked on a mission to explore polymetallic sulphides in a deep-sea rift in the northwest Indian Ocean. The four month expedition, hosted by the ship Xiangyanghong 09, used the manned Jiaolong submersible to conduct some 30 dives in the region. The mission gathered data in advance of China’s application to the International Seabed Authority for mining rights in that area.

Also in the Indian Ocean, the Geological Survey of India (GSI) recently completed a 3-year expedition to generate 181,025 square kilometres of high-resolution seabed morphological data within their Exclusive Economic Zone. Using the research vessels Samudra Ratnakar, Samudra Kaustabh and Samudra Saudikama, the expedition documented millions of tons of lime mud, the presence of phosphate sediment in various locations, gas hydrate off the Tamil Nadu coast, cobalt-bearing ferro-manganese crust from the Andaman Sea and micro-manganese nodules around the Lakshadweep Sea.

Of specific interest to several ISA contractors are the recent NOAA missions to the Central Pacific Basin. The U.S.’ NOAA Office of Exploration and Research has completed three exploration cruises to this under-explored region, and a fourth is underway. The expeditions are part of a three-year Campaign to Address the Pacific monument Science, Technology, and Ocean NEeds (CAPSTONE), a foundational science initiative to collect deepwater baseline information to support science and management decisions in and around U.S. marine protected areas in the central and western Pacific.

Beginning in February 2017, NOAA and partners conducted two cruises on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer to collect critical baseline information of unknown and poorly known deepwater areas in American Samoa, Samoa, and the Cook Islands.

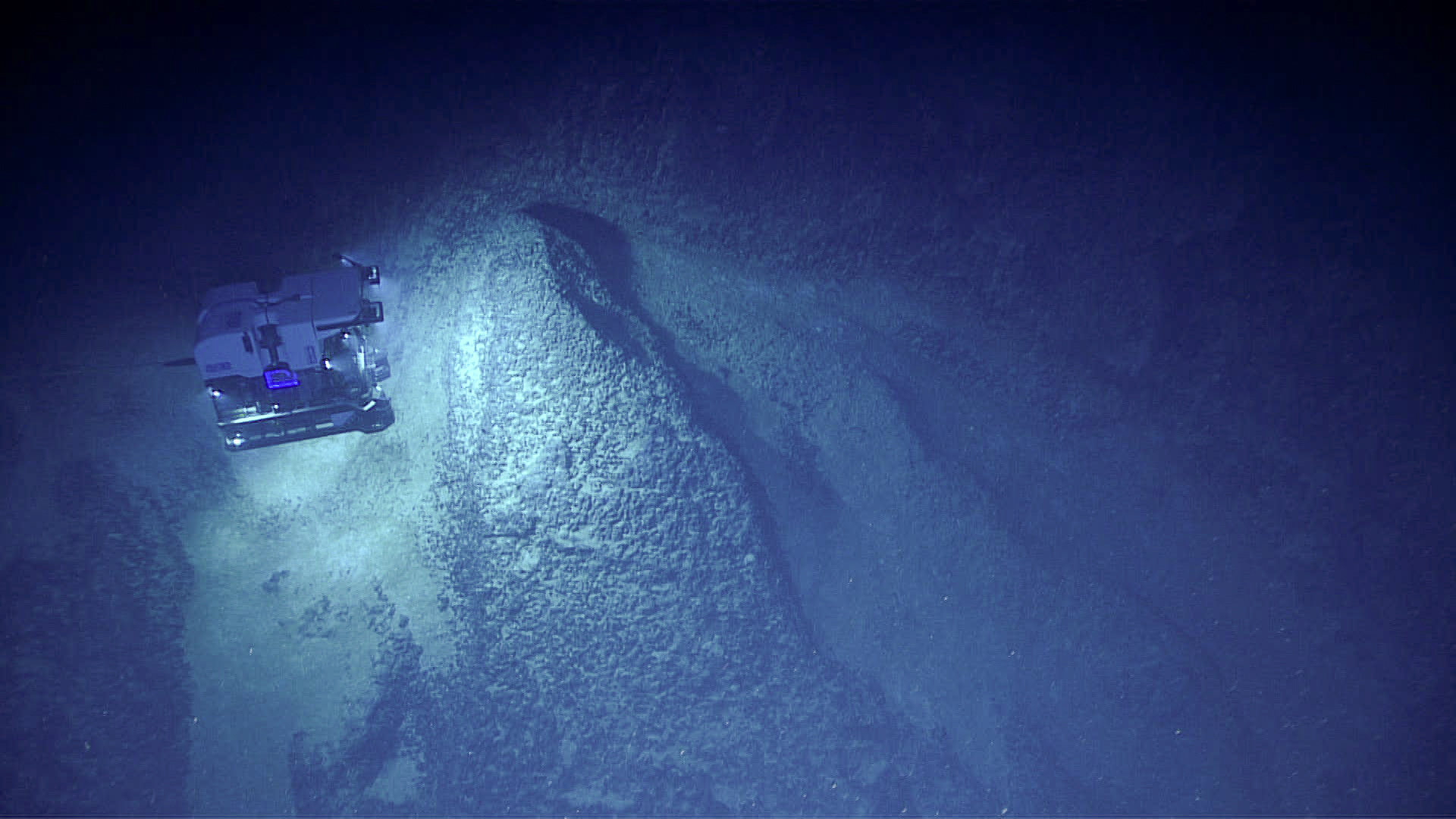

Then, from April 27 – May 19, 2017, Okeanos traversed the vast Pacific area between Pago Pago, American Samoa and Honolulu, Hawai’i as part of the Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin expedition. During Mountains of the Deep, the science team conducted near daily remote operated vehicle (ROV) dives both in U.S. waters and on the high seas. The U.S. portion of the transect included dives in American Samoa and the Jarvis Island, Kingman Reef, and Palmyra Atoll Units of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument (PRIMNM). The high seas portion traversed the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ), a region of interest to the deep seabed mining community for its abundance of polymetallic nodules.

A major driver of NOAA’s decision to explore the Central Pacific Basin was the lack of high-resolution mapping for the region, and that the vast majority of deep sea habitats and geologic features present here remain unseen by human eyes.

During Mountains of the Deep, the Okeanos team covered 2,400 miles while conducting 24-hour operations consisting of daytime dives and overnight mapping operations. Regular ROV dives included exploration of deep-sea coral and sponge habitats, bottomfish habitats, and seamounts. These dives included high-resolution visual surveys and limited sampling.

An important element of the expedition was its collaboration with broader scientific and management communities through telepresence-based exploration. Experts not on board the vessel helped to characterize the study areas using the ship’s deepwater mapping systems, NOAA’s dual-bodied 6,000-meter ROVs Deep Discoverer (D2) and Seirios, and a high-bandwidth satellite connection for real-time ship-to-shore communications. The video stream of the dives was also made available to the public in real time from April 27th to May 19th 2017. During that time, shore-based scientists and students helped guide at-sea operations in real time, greatly expanding the scientific expertise that could be accommodated on the vessel itself. Highlights of the footage they reviewed remain available online.

Intereresting geology at 4570m west Clipperton fracture Zone #Okeanos pic.twitter.com/iJPI04TIIx

— Christopher Mah (@echinoblog) May 8, 2017

As part of the Mountains of the Deep Expedition, NOAA collaborated with broader scientific and management communities through telepresence-based exploration. Using a high-bandwidth satellite connection that was also made accessible to the public, shore-based scientists were able to help guide operations – as well as share their enthusiasm on social media – in real time.

Of key interest to the deep sea mining community was NOAA’s sneak peek at the CCZ. This feature, noted for its abundance of polymetallic nodules, is among the longest tectonic structures on Earth, extending some 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles) from the Line Islands to the Clipperton Transform on the East Pacific Rise. In comparison, this is greater than the distance from New York City to Rome! The CCZ is over 100 million years old and, like other fracture zones in the deep ocean, has high potential for the presence of seeps and deposits of manganese nodules.

On May 8th, Okeanos deployed the Deep Discoverer along the far westernmost edge of the Fracture Zone, diving to abyssal depths up to 4,500 meters (~14,765 ft), the greatest depth attempted on the expedition. Biological highlights on the seafloor included black coral; “bamboo corals including the second deepest ever collected; several holothurians (sea cucumbers); bryzoans; anemones; chitons; carnivorous tunicates (sea squirts); brisingid sea stars; crinoids; scale worms (polynoid polychaete); tube-dwelling fanworms (sabellid polychaete); sea stars; a carnivorous starburst sponge; shrimp; chimera; and a deep ocean lizardfish with highly reflective eyes.” The team also noted aggregations of small sediment-colored spheres or spherules on the seabed, a feature they had previously observed on expedition to the Marianas.

Biologist Astrid Leitner of the University of Hawaii at Manoa was one of the participating scientists on the expedition. She noted that because of the interest in deep sea mining on the Fracture Zone it is all the more important to understand the ecology of the region in advance of any potential mining. One anecdote she shared had to do with our pre-existing notions of abyssal plains and actual biological patterns that are beginning to come clear:

“There seems to be an interesting biogeographic story behind the distribution of abyssal fishes throughout the CCZ and across the Pacific, which we are just beginning to understand. Classically, abyssal plains have been considered to be expansive, homogeneous, and monotonous habitats. However, as we continue to explore the abyssal plains, interesting features – such as fracture zones, abyssal hills, and seamounts – and interesting ecological patterns are beginning to emerge. For example, it seems that rattail fishes are gradually replaced by cusk eels as you move westward across the Pacific.”

Geologic observations were a key component of the Clipperton dive. However, these observations, as well as samples obtained throughout the expedition, are still under analysis and will be reported on more fully at a later time.

This NOAA mission to the CCZ followed closely behind three European marine research campaigns led by JPI Oceans on the RV Sonne, which in 2015 visited several license areas and two Areas of Particular Environmental Interest (APEIs) in the CCZ. That research effort, dubbed ‘MiningImpact’ reported a strong link between polymetallic nodules and biodiversity, and predicted that disturbance impacts would be ecosystem-wide and last for decades.

Since the Mountains in the Deep expedition, the Okeanos has deployed again, this time to the deepwater areas around Johnston Atoll, where they will be exploring seafloor habitats and geology through August 2.

All of these expeditions are helping to establish foundational information and will catalyze further exploration, research, and management activities.