MIKE GAWORECKI on MONGABAY | 26 December 2017

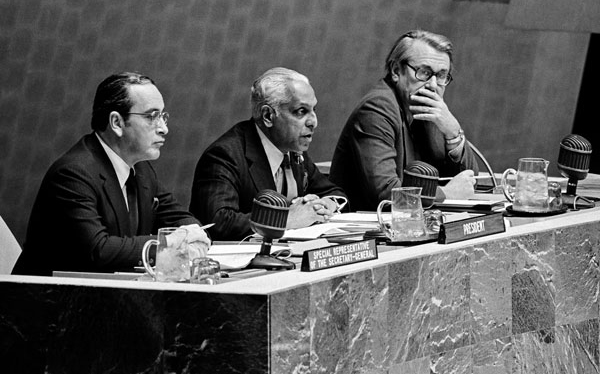

The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a resolution on Sunday to convene negotiations for an international treaty to protect the marine environments of the high seas.

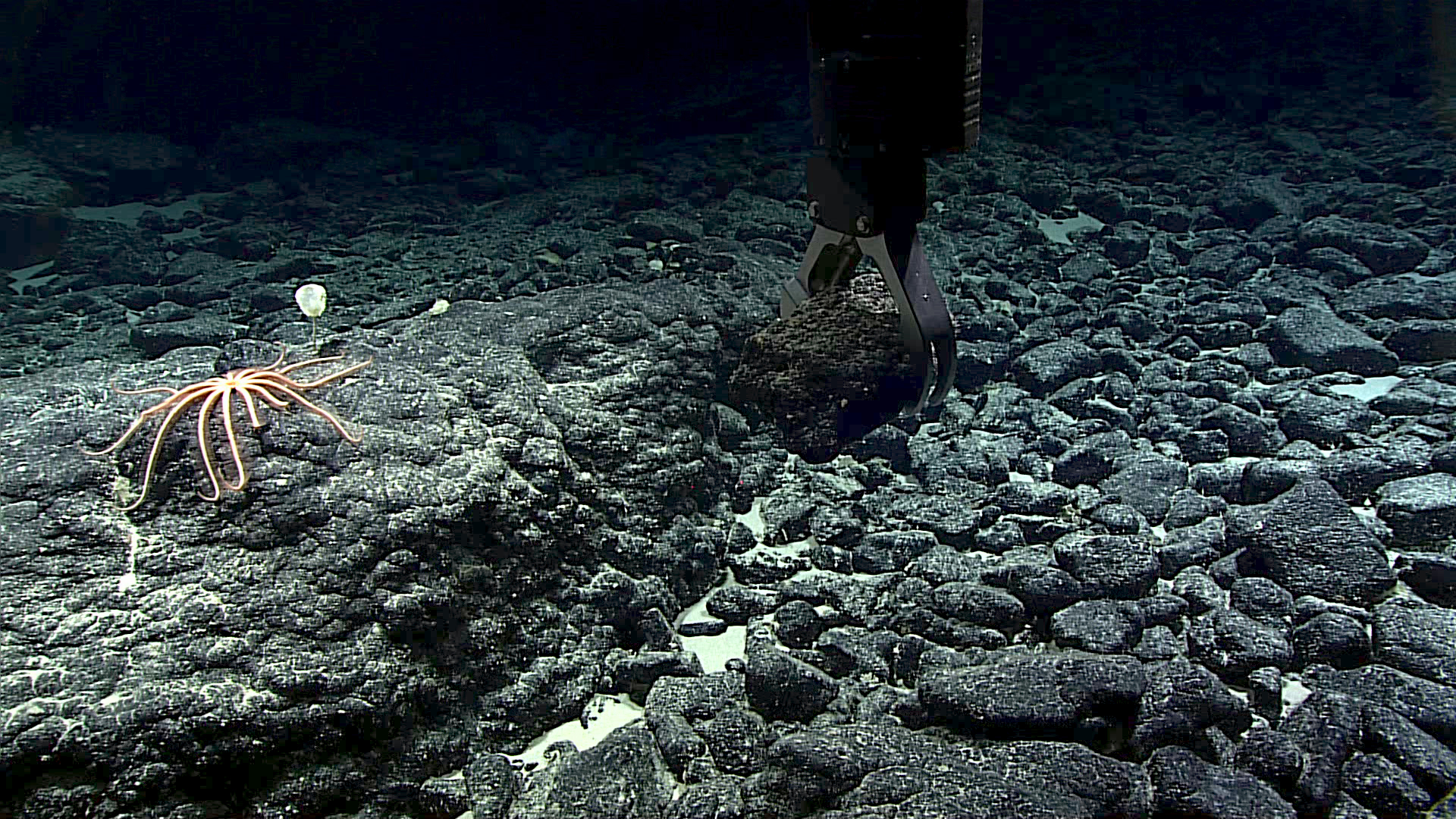

Vast areas of ocean that lie outside any country’s exclusive economic zone — or, in other words, more than 200 nautical miles or more from any country’s shores — the high seas are areas of Earth’s oceans that lie beyond all national jurisdiction. They represent about two-thirds of the oceans, but the high seas are not governed by any one international body or agency and there is currently no comprehensive management structure in place to protect the marine life that relies on them.

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, the treaty would be the first international agreement to address the impacts of human activities like fishing and shipping on the high seas. It would not only create a global system for coordinating the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity, but would also pave the way for the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs) and fully protected marine reserves in open waters.

The UN reports reports that, as of 2017, 5.3 percent of the total global ocean area has been protected. That includes 13.2 percent of marine environments that fall under national jurisdiction, but just 0.25 percent of marine environments beyond national jurisdiction.

Pew’s Liz Karan told Mongabay that high seas fisheries are estimated to account for up to $16 billion annually in gross catch, while estimates of the economic value of carbon storage from the high seas ranges from $74 billion to $220 billion a year. There are regional and sectoral bodies that have a very narrow mandate to look after particular high seas areas, but no body that looks at the ecosystem as a whole. “In these times, with a changing climate, looking at ecosystem resilience is especially important,” Karan said.

The resolution adopted on December 24 had been anticipated since the final meeting this past June of a UN Preparatory Committee, which issued an official recommendation that the General Assembly launch an intergovernmental conference to negotiate a high seas treaty.

“After more than 10 years of discussion, it is encouraging that United Nations member states unanimously agreed to move forward in 2018 with negotiations for an international agreement that would fill the gaps in ocean management to ensure protection for marine life on the high seas,” Karan said in a statement.

“The international community, including scientists and members of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), agrees that at least 30 percent of the world’s ocean should be set aside in MPAs and reserves to achieve a sustainable ocean. Protecting biodiversity on the high seas will be a key component of moving toward this goal.”

The resolution lays out the negotiation process as consisting of four meetings, starting in 2018 and going through mid-2020. The first intergovernmental talks will take place in September 2018, and the final treaty text is expected by the end of 2020.

At the conclusion of its meetings, the UN Preparatory Committee issued a report that made several recommendations of items to be included in an international high seas agreement, but there are still some crucial issues that must be hammered out via treaty negotiations.

“Key questions that the countries will be discussing over the next two years through this intergovernmental conference will be what are the protections that can be taken at an international level, who are the decision-makers, how will that management be conducted and implemented, and then what kind of mechanisms for monitoring, review, and enforcement will follow through to make sure that those protections are not just designated but actually result in conservation benefits and change on the water,” Karan told Mongabay.

Many other conservationists were quick to applaud the UN’s adoption of a resolution to move forward with high seas treaty negotiations, as well.

“This is great news. This vote could open the way to create a Paris Agreement for the ocean,” Maria Damanaki, a former European Union Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries who now works for The Nature Conservancy, told The Guardian on the eve of the adoption of the resolution to move forward with treaty negotiations. “This could be the most important step I have seen in my 30 years working on oceans.”

Follow Mike Gaworecki on Twitter: @mikeg2001