DAVID SHUKMAN on BBC NEWS | 19 February 2018

We’ve drilled the ocean floor for oil and gas, scarred it with trenches for communications cables, poisoned it with old radioactive waste and chemical weapons, and polluted its remotest corners with a blizzard of discarded plastic. So, is mining a step too far?

I put that question to Sir David Attenborough at the launch of his series Blue Planet II. When he sees our video of the giant machines being readied in Papua New Guinea, he is aghast. “It’s heartbreaking,” he says.

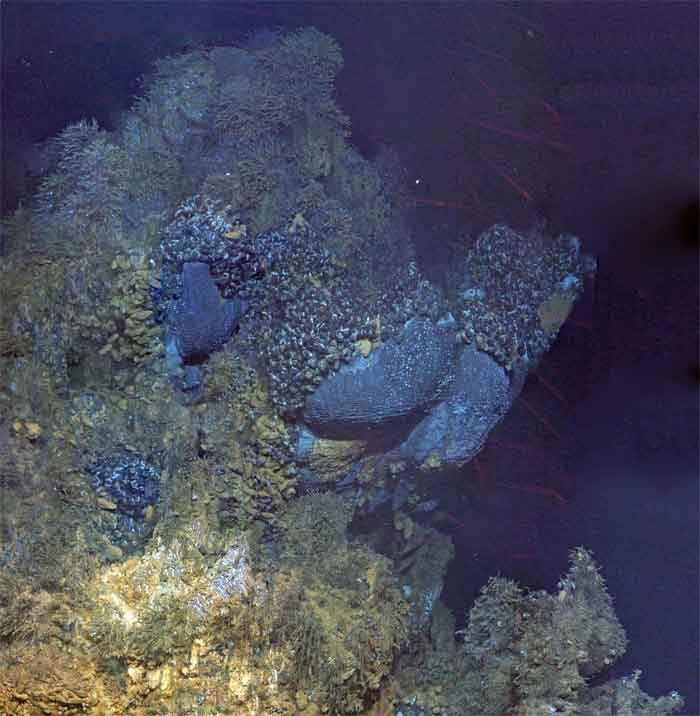

His greatest concern is for the hydrothermal vents, those delicate mineral-rich chimneys which act as oases for unusual creatures.

“That’s where life began, and that we should be destroying these things is so deeply tragic – that humanity should just plough on with no regard for the consequences, because they don’t know what they are.”

But there is a vigorous debate among scientists.

The geologist Bram Murton has warned of “an ill-informed knee-jerk reaction” to ocean mining which, he says, offers the potential to support a low-carbon future.

But Glover says that ultimately it’s about whether it’s right for humans to go into an area and destroy species we know nothing about.

All this raises an awkward set of questions. Where should we get our minerals from? Should phones and wind turbines and electric cars carry a label explaining the origins of their raw materials?

Tins of tuna state that they are “dolphin-friendly” so should products using cobalt say if the metal was mined on land or in the ocean? What would the best choice be anyway? Should the vents so special to Attenborough be spared and only nodule mining allowed?

Some argue that proper recycling of metals would negate the need for deep sea mining in the first place, but others think that that won’t produce a fraction of what’s needed.

Time is running out to come up with answers. More than 40 years since the CIA faked a deep sea mining operation, the first genuine ones may start work far sooner than most people realise.