This has been a strange summer for the online discussion of deep-sea mining. On one hand, there has been an exceptionally high volume of posts about the emerging industry, clustered around the release of several major critical articles in the popular media. On the other hand, due to the relative dearth of major new developments (excepting JOGMEC’s recent announcement of the first cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust extraction) has led to a less diverse pool of stakeholder comments.

Since the February meeting of the 26th Session of the International Seabed Authority we’ve continuously monitored the online conversation surrounding deep-sea mining to gain a broad understanding about how the general public talks about the industry. Caveats abound, as we are limited to data provided by Twitter, written in English, and shared publicly. While it does not provide a comprehensive view of the online discussion, it does provide both a snapshot into one highly active component and insight into how actively engaged stakeholders perceive the deep-sea mining industry.

The tenor of the online conversation has taken a notably negative tone over the last several months, with the hashtags #stopdeepseamining, #defendthedeep, #deeptrouble, #oneoceanoneplanet, #notodeepseamining, and #keepitintheseabed appearing among the top ten hashtags used, alongside more neutral hashtags like #deepsea, #ocean, and #mining.

As in previous analyses, the most active Twitter accounts do not correlate with the most influential Twitter accounts, with only the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition appearing on both lists. The ten most common words used to discuss deep-sea mining were mining, ocean, environmental, impacts, reading, david, attenborough, destroy, ecosystems, and paper, suggesting that Sir David Attenborough’s statement of opposition has had a lasting impact in the public consciousness.

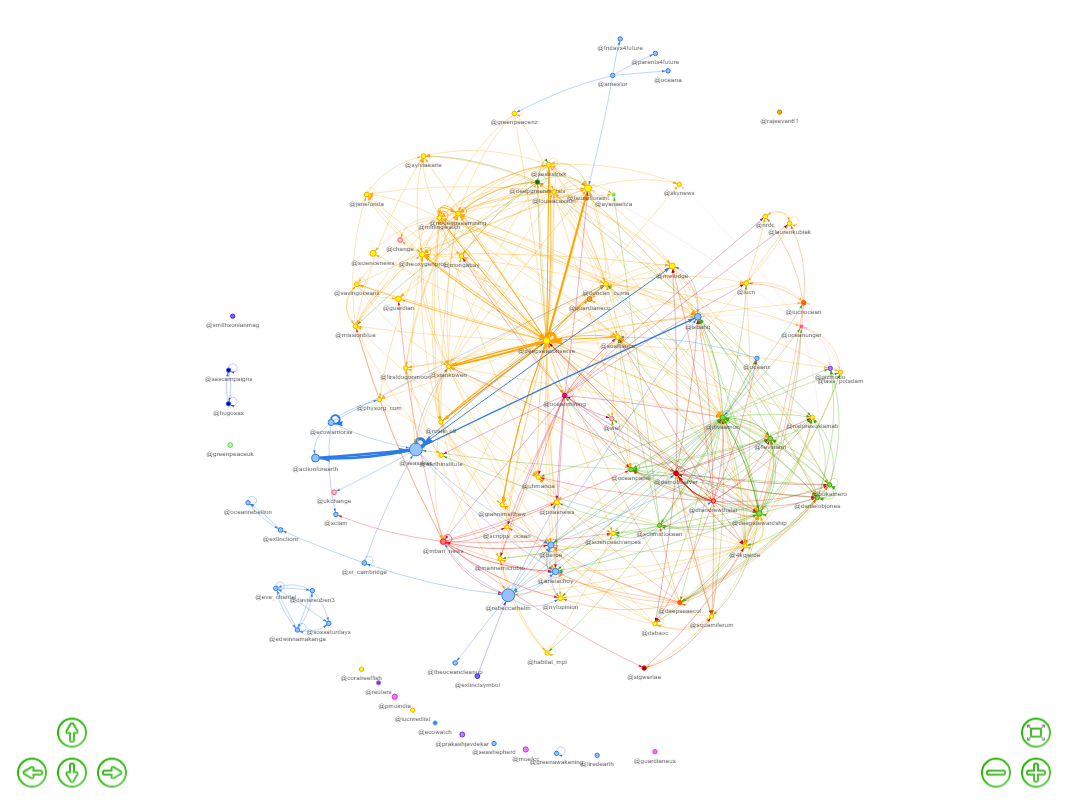

Diving deeper into network analysis, the word network reveals that, wild for the most part the conversation tends to be broadly centralized around a few core themes, there is an outgroup of stakeholders with an exceptionally strong negative sentiment surrounding the industry. Unlike in previous analyses, the user network reveals a much more cohesive network, with far more conversations happening across groups and several central hubs, including Dr. Diva Amon, the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, and Dr. Steven Haddock acting as bridges between diverse stakeholders.

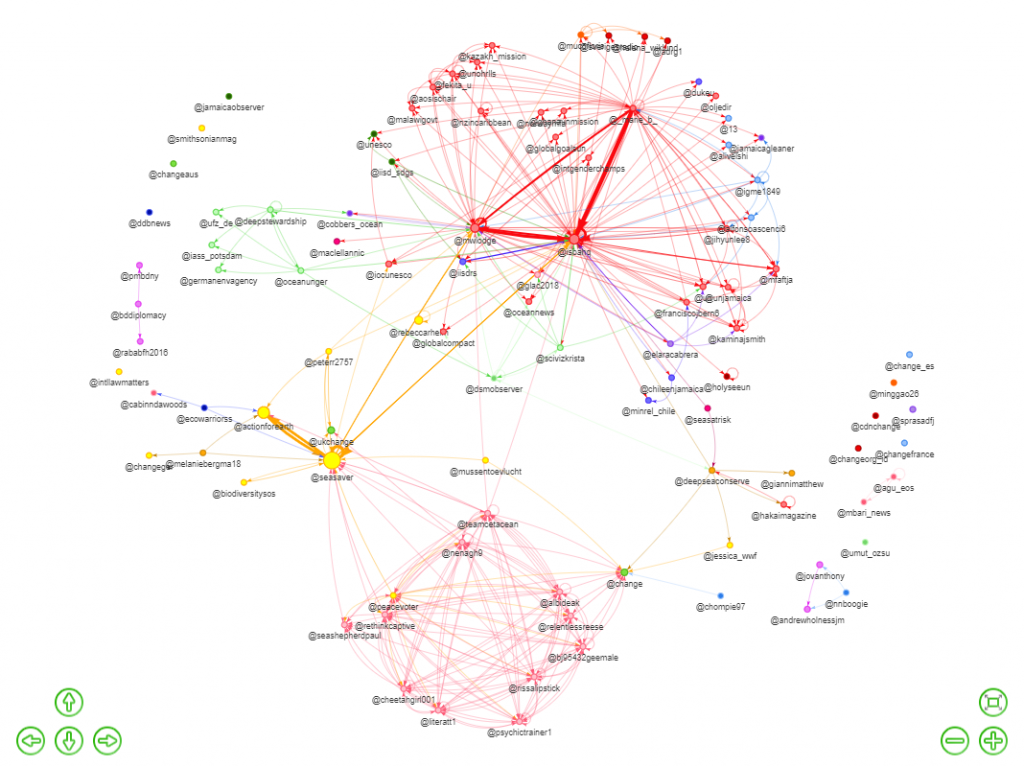

Dialing down to look in more detail at the conversation explicitly about the International Seabed Authority, there are several clear distinctions. Though the hashtag #stopdeepseamining holds the top spot, its volume correlates directly with a moratorium campaign and hundreds of identical tweets. In contrast, the other nine of the top ten most frequently used hashtags are all neutral (i.e. #deepseamining, #isa), descriptive (i.e. #kingston, #jamaica, #isbahq), or related to UN directives (#convention, #sdg14). As above, with the exception of the main ISA Twitter account and the Secretary-General, there was no overlap between the most active users and the most influential users.

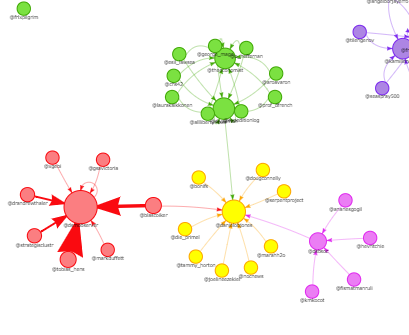

Diving into the network analyses, there were more distinct clusters among the most frequently used words including a large negative cluster focusing on terms like “catastrophe”, “oppose”, and “destroy”, a smaller concern cluster that focused on more cautious terms like “values”, “health”, “prioritise”, and “urging”, and a large procedural cluster which focused on terms related to the structure and function of the ISA.

Within the user network, there were two distinct nodes with few connections–one predominantly composed of stakeholders who had participated in various ISA functions as well as deep-sea researchers, and a second composed of activist groups who were not directly connected to the negotiations. The Blue Planet Society and, to a lesser extent, the Deep-Sea Mining Observer and Deep-Sea Conservation Coalition, served as bridging nodes between these cohorts.

As always, these network analyses provide a snapshot in time of a limited subset of the current English-language online conversation surrounding deep-sea mining. Though limited, they can provide some insight into how civil society and the general public think about and discuss deep-sea mining.