Maria Bolevich for DSM Observer

Transparency builds trust, but deep-sea mining contractors are faced with the challenge of balancing a mandate for transparency under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea with the need to maintain propriety over the privileged information needed to compete in an emerging industry. This balancing act creates an unavoidable tension between the mining contractors (and their sponsoring states), who are working towards an ultimate goal of commercial production and environmental groups advocating for stronger restrictions in the absence of complete environmental data. And yet, for the deep-sea mining industry, it often seems as though it does not matter how committed a contractor is to transparency because actions taken to advance the industry are met with suspicion, by default.

Kris Van Nijen, the managing director of GSR, explains that environmental groups have an easy argument to make–protecting the oceans is a movement most people can get behind—while creating a new mining industry is a harder sell. The image of mining has been tarnished through centuries of biodiversity losses on land, pollution, deforestation, and other environmental and human rights issues.

“That’s why we need to explore other options to obtain the minerals we need,” explains Van Nijen. “We need to take those learnings from the past and do things better going forward. With today’s increased collective environmental awareness: How does a new industry get the chance to do the right thing? Especially an extractive industry? For GSR, we acknowledge it is important that we earn trust, and that we do what we say we are going to do. It’s important that we keep collaborating with world-leading scientists to conduct environmental studies and for independent monitoring of our operations, that we keep partnering and building capacity with developing states – as they want it – so that they too can participate, that we keep striving to do good and with good intentions.”

German historian Ole Sparenberg emphasized that skepticism of the motives of deep-sea miners is baked into the history of the industry. Under the shroud of the Cold War, nations were far more protective of their exploratory capacity. This created vast information asymmetries between nations with access to deep ocean resources and those without. The most striking example of this information asymmetry and lack of transparency, according to Sparenberg, was Project Azorian and the Glomar Explorer. Project Azorian created the impression that deep-sea mining was far more advanced, technologically feasible, and economically profitable than was actually the case in the mid-1970s. This led stakeholders to overestimate the potential profits derived from deep-sea mining that could be redistributed via the yet-to-be-created International Seabed Authority.

But many mining experts approached Hughes’ mining project with skepticism. The scale and the speed of the project was at odds with the estimates of every other company regarding the technological and financial risks. Most companies did not feel the need to rush their own deep-sea mining projects just because Hughes appeared to have moved ahead. They adopted a wait-and-see attitude to learn from whatever the outcomes of this unusual project would be.

“Consequently, I do not want to overestimate the importance of the Glomar Explorer for the history of deep-sea mining as some authors seem to do,” explains Sparenberg. “The CIA’s cover story would not have worked if there had not been a genuine commercial interest in manganese nodules around 1970. Nevertheless, the Glomar Explorer and the CIA’s “Project Azorian” shaped for some years the public perception of deep-sea mining.”

Matthew Gianni of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition argues that the lack of transparency within the International Seabed Authority is among the biggest challenges facing deep-sea mining stakeholders. The decision-making structure of the ISA allows a small number of individuals and a handful of countries to virtually guarantee that a country or company will get a license to mine the deep sea if it applies for one, once the mining regulations are adopted.

“Many of the decisions taken by the ISA are based on recommendations of the Legal and Technical Commission. The meetings of the LTC take place behind closed doors. We see time and time again at meetings of the Council of the ISA that States ask for information from the Legal and Technical Commission and are told that the information is confidential.”

“The LTC in not in a position to verify the accuracy of the information that is in the contractors’ annual reports to the ISA,” say Gianni, “because the ISA does not have the capacity to independently monitor the activities of the contractors. “So, from the point of view of transparency, the ISA has to establish a system of independently monitoring to ensure that what the contractors are doing is what they are required to do, and to ensure that they are in compliance with regulations established by the ISA, in particular on environmental impacts and performance. The exploration contracts and the annual reports of the contractors should be public. These are contracts issued by the ISA on behalf of, and for the benefit of humankind according to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. If someone is writing a contract on my behalf, I want to see what’s in it.”

Not everyone believes the transparency issues at the ISA are insurmountable. Dr. Rahul Sharma, the former Chief Scientist of the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa, India argues that deep-sea mining will be conducted in remote locations where it may not be possible to adequately monitor deep-sea mining. But he argues that this is similar to the challenges of monitoring open-ocean fishing, offshore drilling for oil and gas, and international shipping. “It is incorrect to isolate deep sea mining and associate transparency issues with deep-sea mining, as the issues are the same. With regulations in place, modern techniques available and data provided by the operator, compliance will have to be monitored by ISA. Deploying neutral observers randomly could be another way, but to deploy them at every location and for extended periods of time, may not be practical,” says Sharma.

Van Nijen emphasizes that, though contractors have to maintain control over proprietary data, the information most essential to civil society, environmental data, already is and will continue to be made publicly available. “It is also important that we gain a shared understanding about when information needs to be made public. Research data can always be improved; so we need to be careful when we say something, it is correct. So, this requires more data and research to be sure. Sometimes things change along the way. We are also learning,” says Van Nijen. “Mining is not yet happening; the industry is still in the exploration and research phase; all the information currently being gained will inform future operations, impact assessments, environmental management and monitoring plans, the mine plan, closure plan, etc. – much of which will become public should an application for mining be made.”

“The world needs more metal,” Van Nijen concludes. “And we should be exploring all options to meet that demand, including new options. The deep seabed may be one of the more responsible solutions out there. We are doing the research to find out.”

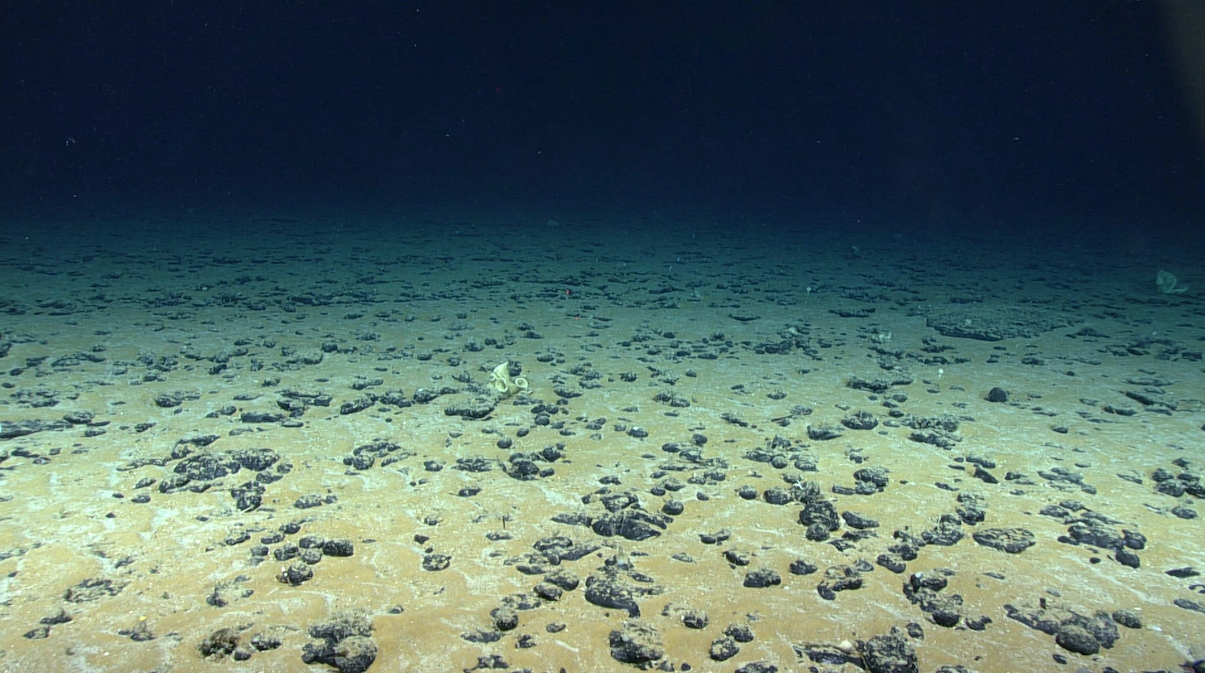

Featured Image: Polymetallic nodules. Image by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.