One of the small but persistent puzzles of the deep abyssal plain is the question of how polymetallic nodules manage to stay above the sediment. Large nodules form over millions of years as minerals precipitate out of seawater, and yet, despite a light dusting of sediment continuously raining down from the surface, they somehow remain above the seafloor. Nodules are rarely found completely buried by sediment. Though the sedimentation rate in the abyssal regions where they form is exceptionally low, even the sparsest depositions will accumulate into thick layers over the multi-million-year lifespan of a polymetallic nodule.

So why do we find nodules exposed at the surface and not tens of centimeters beneath the seafloor?

A new paper by Adriana Dutkiewicz, Alexander Judge, and R. Dietmar Müller attempts to answer this question while examining the global distribution of polymetallic nodule fields to predict where nodule fields will occur. They found that nodule fields were most common in regions with low surface productivity and benthic biomass, where the seafloor was comprised of clay or calcareous ooze, and where sedimentation rates were, unsurprisingly, low.

To address the question of why nodules don’t become buried, they tested two competing hypotheses: that bottom currents were significant enough to prevent sediment from accumulating on the nodules and that the movement of benthic infauna was enough to continuously disturb the sediment and push nodules to the surface. Flow models revealed that bottom currents would not be sufficient to keep the nodules uncovered, but estimates of infauna activity indicated that the movement of burrowing organisms was enough to disturb the sedimentation layer and push nodules towards the surface.

“Organisms such as starfish, octopods and molluscs seem to keep the nodules at the seafloor surface by foraging, burrowing and ingesting sediment on and around them,” said Dr. Dutkiewicz in an interview to Geology In. “Although these organisms occur in relatively low concentrations on the abyssal seafloor, they are still abundant enough to locally affect sediment accumulation.” In other words, it’s the very organisms that environmental NGOs want to ensure are protected that are responsible for maintaining nodule fields as attractive and commercially viable resource to be extracted.

In addition, the research also predicted as yet undiscovered nodule fields in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Though biomass limited, the abyssal plains are staggeringly diverse, and that diversity may be essential to nodule field formation. This new insight can help inform the development of regional environmental management plans as well as guide contractors to new potential lease blocks in unexplored regions of the deep sea. “Our conclusion is that deep-sea ecosystems and nodules are inextricably connected,” says Dr. Dutkiewicz.

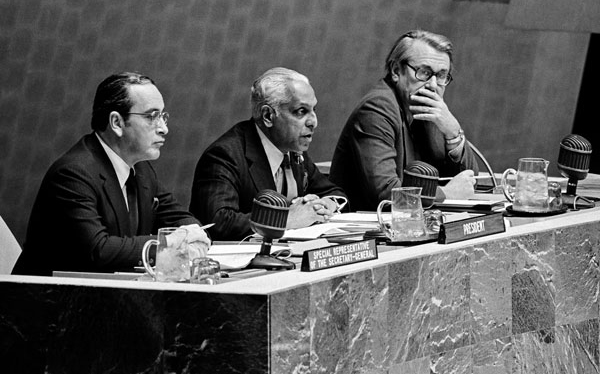

Featured photo provided by the Utah Geological Survey.