While negotiations rage within the halls of the International Seabed Authority over the draft mining code, the operationalization of the enterprise, and the development of the financial model, a second conversation is happening, distributed across the internet and engaging an entirely different cohort of stakeholders. Deep-sea mining attracts a passionate collection of activists, technologists, policy wonks, and futurists interested in diving deep into the subject but waylaid by a dearth of information and engagement from the principal players.

During part I of the 26th Session of the International Seabed Authority Council meeting, and for the weeks following the meeting, the DSM Observer performed a sentiment analysis across a range of keywords used by stakeholders to discuss the deep-sea mining industry online. We assessed two sets of keyword groups: a general set revolving broadly around the concept of deep-sea mining and a specific set related to discussions surrounding the International Seabed Authority and the 26th Session of the ISA. And yes, we did account for that desultory hyphen.

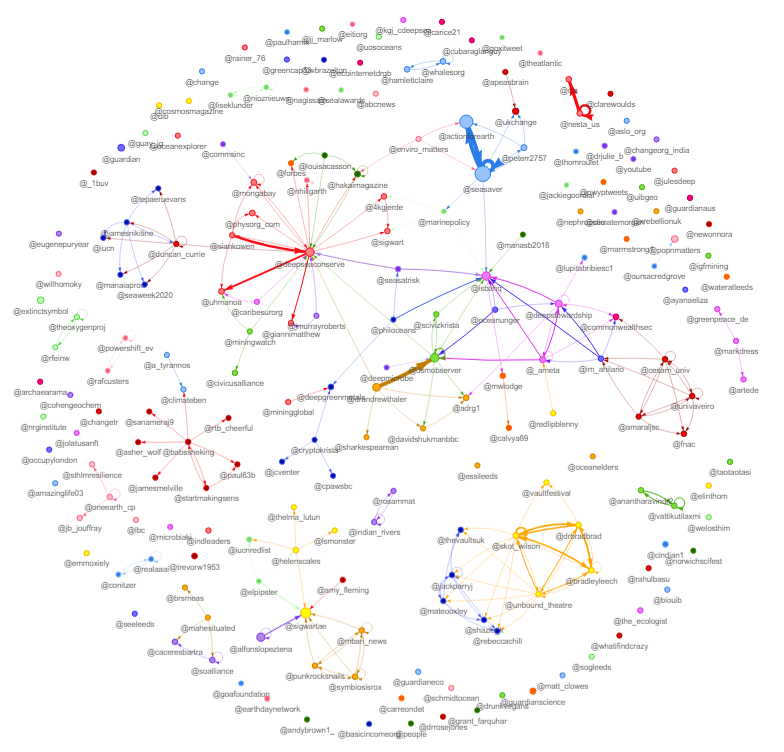

By examining how social networks form online and analyzing structural connections (or lack thereof) among stakeholders, contractors, member states, NGOs, and the International Seabed Authority itself can better craft and implement stakeholder outreach campaigns.

Between February 9 and March 11, deep-sea mining was mentioned on Twitter 841 times, with a spike in activity on February 26, 2020, a few days after the conclusion of the ISA Council meeting and following an article in the Guardian about threatened snails at seafloor massive sulphide deposits. Sentiment analysis was generally neutral, with the most frequent words being descriptive (mining, ocean, floor, areas, large) or connected to the Guardian article (snails, super, weird, mission). Only one of the ten most common words used in tweets related to deep-sea mining was overtly negative (destroy). The red face with an angry expression emoji was the fourth most commonly used emoji, and the only one that expressed any overt sentiment.

Hashtag use clustered around the usual suspects, including #deepseamining, #deepsea, #isba26, #defendthedeep, #ocean, #mining, #sdg14, #stopdeepseamining, #biodiversity, and #population. Consistent with general trends in social media, the most active accounts did not correlate with the most influential accounts. Only the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (@deepseaconserve) registered among both the most active and most influential accounts. General ocean activist accounts, including @seasaver, @actionforearth, as well as deep-sea mining specific groups, like @deepseastewardship, and @deepseaconserve, topped this list of most influential accounts, followed by individual scientists, the ISA account, and media accounts like @guardian and, of course, the Deep-sea Mining Observer. Notably absent were any accounts from contractors or explicitly pro-industry groups.

The real meat of a sentiment and network analysis like this is digging into the connections among people discussing deep-sea mining online. The network analysis reveals a highly fractured social seascape. Many stakeholders from a variety of backgrounds are talking about deep-sea mining, but they are not talking to each other. Mapping the connections between the 200 most influential Twitter users in the deep-sea mining discussion reveals a core, multi-hubbed network centered around the ISA, the Deep-sea Mining Observer, the Deep-sea Conservation Coalition, and the @seasaver account. An entirely separate cluster appears around users discussing the Guardian article, while a third cluster is related to a forthcoming play which heavily references deep-sea mining. The final large cluster is centered around more conspiracy-minded users sharing a viewpoint not necessarily grounded in reality. Though easy to dismiss, it should be noted that users in this final cluster are among the most vocal individuals discussing deep-sea mining online.

In addition to these main clusters, the bulk of users discussing deep-sea mining online do not engage with any principles involved in any aspect of the industry. This indicates that there is a broad cohort of stakeholders who are not being reached by current outreach campaigns.

Note: we intentionally cut off our analysis before the news broke that David Attenborough called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, in order to more accurately reflect the baseline conversation.

Between February 9 and March 13, the International Seabed Authority was mentioned 885 times, with no particularly overwhelming spikes in activity nor any strong correlation with more general discussions about deep-sea mining. Sentiment was entirely descriptive, indicating that most tweets about the Authority serve to explain what the Authority is, rather than how people feel about the Authority. A recent cluster of tweets directed at the Authority following Attenborough’s call for a moratorium did not push the discussion above the baseline. This suggests that while there is an animated discussion happening surrounding deep-sea mining, few are directly connecting the concept of mining the Area with the regulatory body working to operationalize it.

Unlike the more general analysis of deep-sea mining, the network of users engaged in discussions about the ISA was more tightly clustered around a clear set of central hub accounts, include the ISA’s main account, Secretary-General Michael Lodge’s account, the IISD, the Deep-sea Mining Observer, and the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative.

So what are the big takeaways from an analysis like this? The networks reveals that there is a significant gap between the more general discussions of deep-sea mining, often driven not just by NGOs, but by NGOs who aren’t generally engaged in the actual deep-sea mining negotiations. The preponderance of halo organizations–those with shared interest in the industry but little direct engagement–means that the online conversation is not being driven by those most engaged in developing or regulating the industry. This can often lead to the promotion and propagation of misconceptions about the state of the industry (one highly-active Twitter account, for example, frequently insists that deep-sea mining has already depleted the oceans of oxygen). The constant refrain that deep-sea mining is a gold rush, despite the fact that the 50-year-old industry has yet to reach production and that, in the most diplomatic of times, the negotiation process is best-described as “stately”, endures because of this phenomenon.

There is significant space for contractors to engage in stakeholder outreach to help fill the information gap. Of the major contractors, only one has a substantial online presence. And while it’s understandable that contractors are generally resistant to these kinds of outreach campaigns, their absence from the social media seascape does leave a void in the conversation.

The analysis also reveals that there is a clear strategy available for the ISA to more directly engaged with concerned stakeholders who, though apprehensive about the development of the industry, are unaware of the process and structure behind this advancement.

One thing that contractors and environmental NGOs can agree on is that it would be a shame if the effort deep-sea mining companies have invested into understanding the environmental impacts and creating good environmental policy went unacknowledged.