Andrew Thaler for the DSM Observer

On Wednesday, March 30, several major technology and automotive companies joined the deep-sea mining moratorium movement. Google, BMW, Volvo, and Samsung SDI (a Samsung subsidiary responsible for manufacturing small lithium-ion batteries for smartphones and other applications) signed on to the World Wide Fund For Nature’s Global Deep-sea Mining Moratorium Campaign. These are the first major corporations to commit not to source minerals from the deep seabed or finance deep-sea mining activities, and to exclude seafloor minerals from their supply chain.

“Sustainability leaders should be concerned about how their green image could be affected by incorporating deep sea minerals into their metal supply chain,” says Kristina M. Gjerde, Senior High Seas Advisor to the IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme. “Deep sea minerals are not solving the problem of harmful impacts, just relocating it elsewhere, where the affected communities are less able to speak for themselves. Moreover, it should be clear by now that relocating mining to the deep sea is unlikely to reduce the issues associated with terrestrial mining. By increasing the availability of minerals, deep sea mining could in fact make it harder to clean up terrestrial mining activities.”

As major automotive manufacturers in the midst of a pivot to electric vehicles, BMW and Volvo’s announcements represent a potential threat to the deep-sea metal market. BMW expects 50% of all its vehicle sales to be electric by the end of the decade, with several BMW subsidiaries, including Mini, producing only EVs by 2030. Volvo, who also intends to be fully electric by 2030, recently shipped its first all-electric vehicle to the United States, though software issues caused the long-awaited XC40 Recharge to be held in port pending a critical system update.

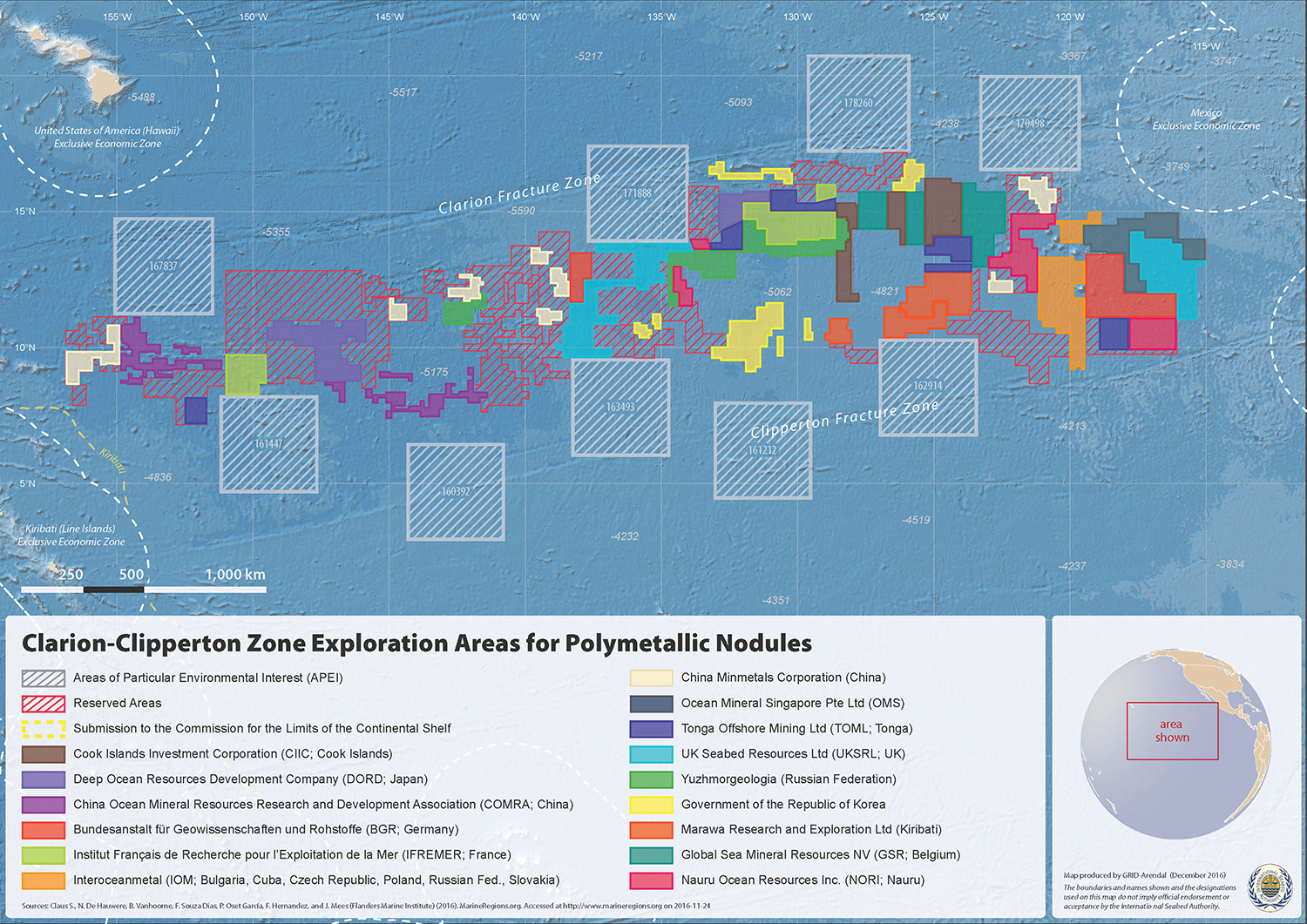

DeepGreen, a deep-sea mining company with several polymetallic nodule leases in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, emphasized that the environmental studies WWF is calling for are the same studies that mining contractors are conducting in conjunction with the International Seabed Authority. “The science that WWF is calling for is the same science we are doing,” a DeepGreen representative stated in a press release. “No extraction of ocean nodules can take place until rigorous, multi-year environmental impact studies are conducted, vetted, reviewed and approved. If this peer-reviewed science, which is a major contributor to society’s knowledge of the deep sea, shows that the risks outweigh the benefits, the global community through the International Seabed Authority — not WWF — can decide that extraction will not occur.”

Gerard Barron, CEO of DeepGreen, expressed frustration that the brands didn’t reach out to understand the mining contractors’ position before announcing their support for a moratorium. “I just don’t fathom how anyone could come to a conclusion without talking to both sides,” says Barron, who also expressed optimism that this new attention would ultimately benefit the industry. “Thank you for getting it on the agenda,” he said, referencing WWF. “Discussion means we can put forward the argument for why this is the only sensible choice.”

Kris van Nijen, the Managing Director of deep-sea mining company GSR, does not see an inherent conflict with the WWF announcement and their current operations. “Deep seabed mining is an industry in the exploration, research and development phase,” Van Nijen says in a press release, “Years of detailed scientific work lie ahead before there is any prospect of commercial activity. The research that campaigners are calling for is required by the International Seabed Authority. In effect, campaigners are simply, and rightly, asking for the current regulatory processes to be followed and requirements applied.”

Kris Van Nijen provided an opinion editorial to the DSM Observer, in which he argues that, far from disagreement, it seems that “Harmony has broken out in the world of deep-seabed mining.”

Matthew Giani, Political and Policy Advisor for the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, believes that the need-based case for deep-sea mining is overly optimistic. “Using a true life cycle sustainability analysis,” Gianni argues, “it is clear that BMW, Volvo, Samsung SDI and other battery manufacturers do not need to get the metals to build batteries from mining the [Clarion-Clipperton Zone] or tropical forest areas for nickel, cobalt and manganese. It is possible to build batteries without any of these metals and in fact cobalt and nickel free batteries are already on the market. Tesla recently began selling EVs with Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries – no nickel, no cobalt – and they are selling unexpectedly well according to a recent article published by Mining.com.”

On the heels of the WWF announcement, Greenpeace International initiated a direct action campaign against a DeepGreen vessel in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone and a GSR vessel at port in San Diego. Activists help up banners declaring “Stop Deep Sea Mining!” and “Protect the Oceans!” in front of both ships. In conjunction, Greenpeace called for the ratification of a Global Ocean Treaty, which would allow for the creation of ocean sanctuaries in the high seas. “It was nice to see them” said Gerard Barron, whose vessel was one of the targets of the protest, “they were very respectful protestors and we appreciated that.”

“Governments must agree on a Global Ocean Treaty in 2021 as a stepping stone towards protecting the ocean until we can reach consensus to ban deep-sea mining permanently,” says Arlo Hemphill, a Greenpeace USA Senior Oceans Campaigner and the previous Editor-in-Chief of the Deep-sea Mining Observer in a Greenpeace press release. “A treaty would allow us to protect vulnerable deep-sea habitats on the high seas within ocean sanctuaries, something currently not possible under international law.”

At the heart of the issue is where responsibility for determining what constitutes acceptable environmental risk lies. Under the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea, that duty falls to the International Seabed Authority, who is empowered by the Convention to ensure that the development of deep-sea mining is not harmful to the environment. However, many organizations argue that the ISA’s dual mandate, to both promote the development of deep-sea mining and ensure environmental protections places the Authority in an impossible position.

Environmental groups claim that the ISA’s dual mandate presents an irreconcilable conflict of interest and that without independent assessments, the ISA’s determination of acceptable environmental impacts cannot be trusted. That impression was not helped by an interview ISA Secretary-General Michael Lodge gave for the Atlantic last year, in which he appeared all but entirely dismissive of environmental concerns.

“This is far broader than the ISA mandate,” says Jessica Battle, Senior Expert on Global Ocean Policy and Governance and Lead of the Deep Seabed Mining Initiative at WWF, “and therefore needs a much broader assessment by many more actors than those involved at the ISA. It is about a broader societal acceptance. Then, of course, once all these issues have been investigated and addressed, during the time of a moratorium, then the ISA should be able to make a decision. But we are far from that point today.”

“The questions that ISA members should ask themselves,” says Gianni, “are one – can deep-sea mining be managed to prevent significant damage to species, ecosystems in the deep-sea? If not, then two – is it necessary for the world to mine the international deep seabed area? In this, it is important not to confuse the economic viability of deep-sea mining with a societal necessity to mine the deep sea. Finally, if the answer to the first two questions is no – which to me is the correct answer based on the best scientific information available today and the fact that alternatives to metals from deep-sea mining are available to build renewable energy technologies – then ISA member countries need to ask themselves – should the ISA permit any deep-seabed mining at all?”

It’s not just the two major corporate contractors who have a major financial stake in the future of deep-sea mining. State-sponsored contractors (though all deep-sea mining contractors must be sponsored by a member state in order to obtain an ISA-issued mining exploration or exploitation lease, state-sponsored contractors are financially supported either in part or in whole by their home country) make up the bulk of the exploration licenses issued by the International Seabed Authority.

Dr. Se-Jong Ju of the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology responded in his personal capacity regarding the impact, in particular, of Samsung SDI’s announcement may have on Korean contractors: “Although it is impossible to predict any special impact because [deep-sea mining] has not entered the exploitation stage in earnest, I believe it is likely to be a negative impact for deep-sea low-resource development in the long- and short-term.”

Several countries are pursuing deep-sea mining within their national waters. Norway recently announced the first phase of an environmental impact study that could lay the foundation for deep-sea mining within Norway’s exclusive economic zone in the near future. Mineral deposits within Norwegian waters include seafloor massive sulphides containing copper, zinc, cobalt, gold and silver as well as crust formations containing lithium and scandium. Norway, along with other Scandanavian countries, has begun divesting from fossil fuel, creating space for the country’s significant offshore operations capacity to expand into other industries. A parliamentary vote on opening areas of the Norwegian EEZ to mineral exploration is scheduled for the second quarter of 2023.

China and India have initiated major deep-sea mining campaigns, both in areas beyond national jurisdiction and within each country’s respective EEZ. India, notably, has committed billions of dollars to expanding their deep-sea exploration capacity and has begun trialing a benthic crawler that will collect nodules from deposits within India’s exclusive economic zone as well as ISA lease blocks in the Indian Ocean.

Japan was the first country to successfully extract ores from a commercial deep-sea mineral deposit, first from a seafloor massive sulphide and then a cobalt-rich crust. Though there was significant fanfare for these first-to-extraction endeavors, there have been few updates following initial extraction tests and no indication that ongoing extraction efforts are currently underway within Japan’s EEZ.

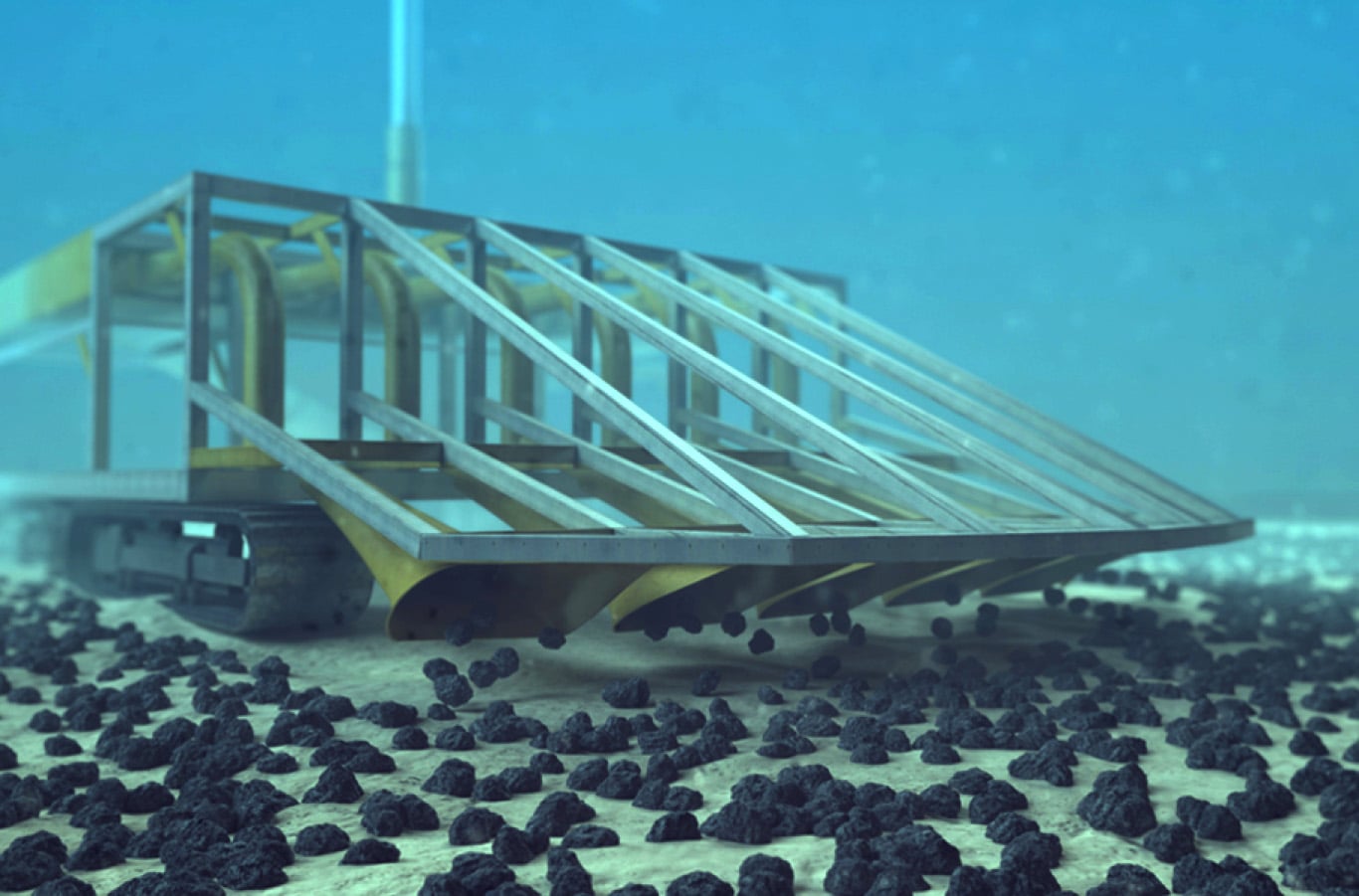

No deep-sea mining can occur in the Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction until the International Seabed Authority finalizes regulations for the exploitation of seabed resources outside of national boundaries. All international efforts are currently in the exploratory, technology testing, and environmental impact assessment phase. While there have been several small scale experimental deep-sea mining initiatives within national waters, there is currently no commercial deep-sea mining for seafloor massive sulphides, cobalt-rich crusts, or polymetallic nodules under way anywhere in the world.

For Gerard Barron, one of his biggest frustrations is that he feels it is unfair to lump multiple types of deep-sea mining into a single category. The impacts of nodule mining, he points out, is very different from the impacts of cobalt crust or polymetallic sulphide mining. But the WWF views the entire industry with the same level of skepticism. “There are no distinctions on the ‘kind’ of mining, instead there is a need to take pressures off the ocean, not add additional pressures to it, in order to restore its ecosystems and build its resilience. The statement thus includes deep seabed mining without distinction,” says Battle.

We reached out to BMW, Volvo, Google, and Samsung SDI, but did not receive a response by date of publication. The International Seabed Authority declined to comment.

Featured Image: Protest against Deep Sea Mining in the Pacific, photo by © Marten van Dijl / Greenpeace.