Andrew Thaler for the Deep-sea Mining Observer

Twenty-eight years ago, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) gathered in Jamaica for the first time to establish the regulations, standards, and guidelines governing how mineral resources—resources that under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea are the “common heritage of mankind”—would be mined from the ocean floor. During the nearly three decades since, delegations from 167 nations and observers from advisory groups, non-governmental organizations, and civil society have, through conflict and compromise, slowly and methodically eked out a path towards commercial exploitation of deep-sea resources that lie beyond the reach of any nation’s borders.

This stately-by-design process was thrown into disarray last summer, when, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Republic of Nauru invoked an arcane instrument within the ISA’s founding documents, Annex I, Section 1(15) of the 1994 Agreement on the Implementation of Part XI of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, colloquially known as the Deep-sea Mining Trigger. Upon notification of intent to submit a plan of work for commercial deep-sea mining, the trigger begins a 2-year countdown, during which time the ISA must either finalize the regulations for deep-sea mining or consider the submitted plan of work in the absence of a formal Mining Code. Under this new, expedited regime, and still limited by a global pandemic, the member nations of the ISA have until June 30, 2023, to agree upon a Mining Code for the exploitation of seabed resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

“[The Trigger] has become the Sword of Damocles,” declared the Chilean delegation during least week’s ISA meeting. “It gives rise to the possibility that an agreement entered into in good faith, which did not provide for the possibility of a pandemic on a global scale, would now see exploitation rules be agreed upon without necessary regulations in place to ensure the protection of the common heritage of mankind.”

As the driving force behind the invocation of the Trigger, The Metals Company has taken center stage in the deep-sea mining debate. They own the mining contractor partnered with the Republic of Nauru, Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), and it is The Metals Company who will ultimately have the capacity to carry out Nauru’s plan to mine the seabed. With its support vessel, the MV Hidden Gem, completed; extensive sea trials for its nodule collector and riser and lift system underway; and an ever-growing body of scientific literature to support their position as a more environmentally conscientious form of mining, The Metals Company seems poised to become the first deep-sea mining company to enter into commercial production. Earlier this month, they announced a partnership with Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific Industrial Research Organization to lead the development of their environmental management and monitoring plan.

Their financial position, however, suggests a different story. Unique among deep-sea mining companies, The Metals Company is dependent on attracting private investors. All other companies that currently hold ISA-issued mining exploration contracts are either state-funded entities or subsidiaries of larger, more diversified corporations. Plagued by a weak public offering and the failure of key investors to deliver promised funds following a reverse merger, their stock price currently sits at $0.87, far below their all-time high of $15.39. They are entangled in several lawsuits, some initiated by The Metals Company against their missing investors, others initiated by shareholders claiming that they were misled about the financial position of The Metals Company.

At the heart of the class action suits are the claims that The Metals Company overvalued its Tonga Ocean Minerals Limited (TOML) holdings and exaggerated the costs of the NORI operations. In 2020, The Metals Company acquired the TOML mining lease from Deep Sea Mining Finance Ltd, a holding company created after the liquidation of Nautilus Minerals to manage the defunct company’s remaining assets. The $43 million TOML license was valued several orders of magnitude higher than similar mining contracts already in The Metals Company’s portfolio, including NORI’s mining license (valued at $250,000) and an option to secure the Marawa mining license (valued at $198,855). According to the class action suit, the TOML acquisition involved a transfer of 7.8 million shares to Deep Sea Mining Finance, representing 3.4% of The Metals Company’s outstanding shares.

“We believe the TOML license acquisition was a payout to undisclosed insiders at the expense of misled minority TMC shareholders,” states the class action suit filed in the US Eastern District of New York. The Metals Company denies these claims.

Further compounding the political complications of the sale, Deep Sea Mining Finance Ltd. is a joint venture between Oman-based MB Holding Company LLC and Metalloinvest, a Russian mining investment firm whose majority shareholder is Alisher Usmanov. Usmanov is among the oligarchs currently sanctioned by the United States and European Union as a result of the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine.

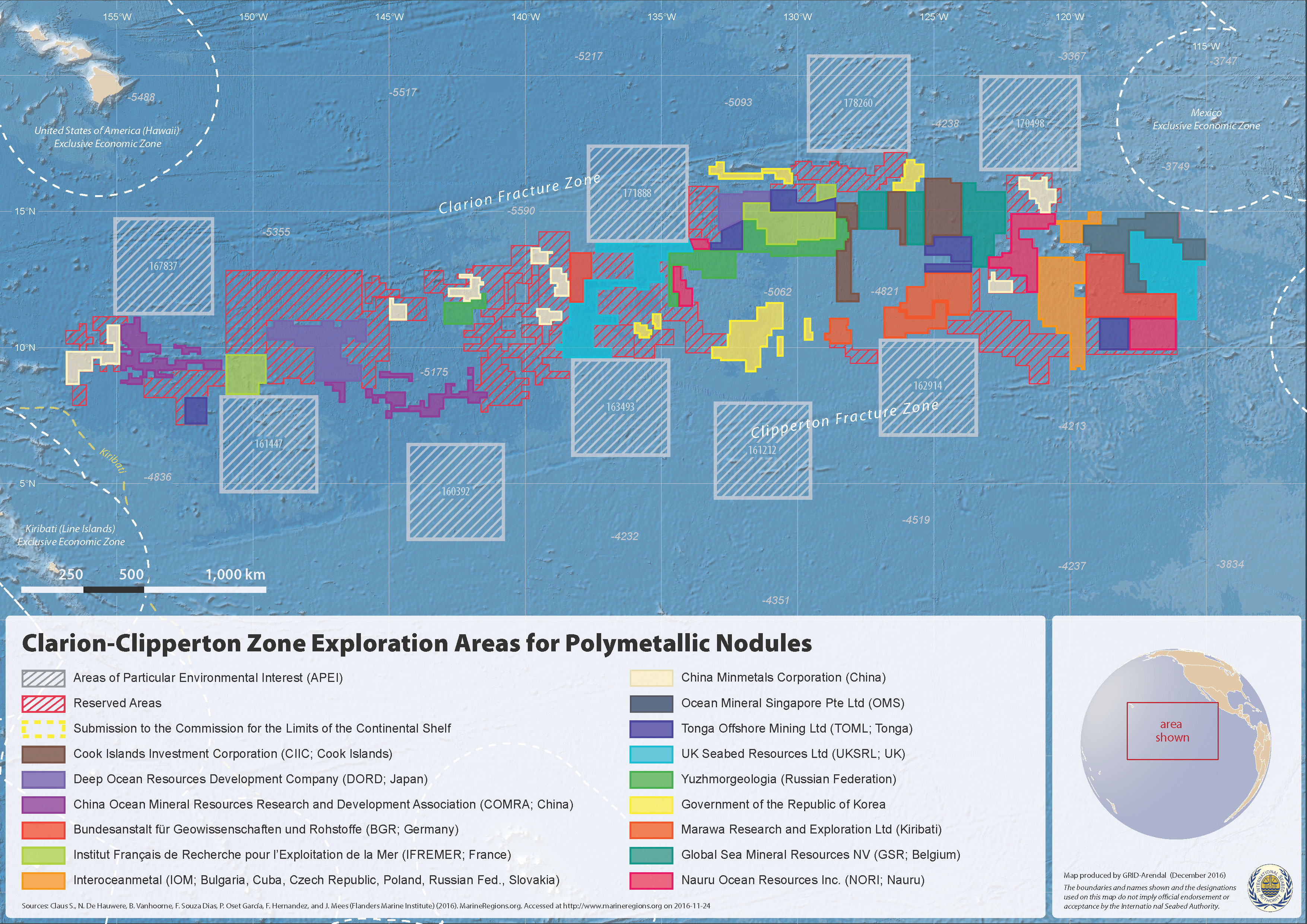

A common source of confusion to those not immersed in the nuances of deep-sea mining contractors: while nations must sponsor mining companies who pursue exploration and exploitation leases, the purview of the ISA is the seafloor beyond national borders. Both the TOML and NORI mining exploration leases, as well as the Kiribati-sponsored Marawa license, are for areas of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, a vast field of polymetallic nodules in the middle of the Pacific. If successful, NORI’s exploration lease, which gives them permission to assess the seabed and determine the value of any potential mineral prospects, as well as conduct preliminary environmental impact assessments, would be converted to an exploitation contract, which allows them to mine the ore commercially.

Nauru’s invocation of the two-year trigger in support of NORI and The Metals Company may have backfired within the ISA. As the Second Part of the 27th Session of the International Seabed Authority Council closed its first week of meetings, more and more member states voiced their disapproval with the trigger’s invocation and their frustration with being forced to negotiate such a complex piece of international law under what they feel is an artificial timeline.

“[The ISA] needs to head the alarm bells,” emphasized the delegation from France during the recent meeting, adding that they do not view the invocation of the trigger as an obligation to approve any plan of work. France sponsors its own deep-sea mining contractor, IFREMER, and holds an ISA-issued mining exploration contract for seafloor massive sulphides on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

This has ultimately led a formal declaration by a member state in support of a moratorium on deep-sea mining to limit the development of the industry until there is a greater understanding of the potential environmental impacts on the deep seafloor. The Federated States of Micronesia announced that they had joined the Alliance of Countries for a Deep-sea Mining Moratorium along with several other Pacific Island nations. “The Ocean is a unitary whole,” declared the delegation from the Federated States of Micronesia, “and what happens in the international seabed Area could very well impact coastal waters and territories.”

This was the first time in the history of the ISA that a member state called for a moratorium on deep-sea mining during a formal Council session. Other countries made their preferences for moratoria, or some other flavor of a pause on the development of the industry, known through informal sessions or through other mechanisms. France’s president Emmanuel Macron notably expressed his nation’s preference for moratorium during the recent UN Oceans Conference in Lisbon.

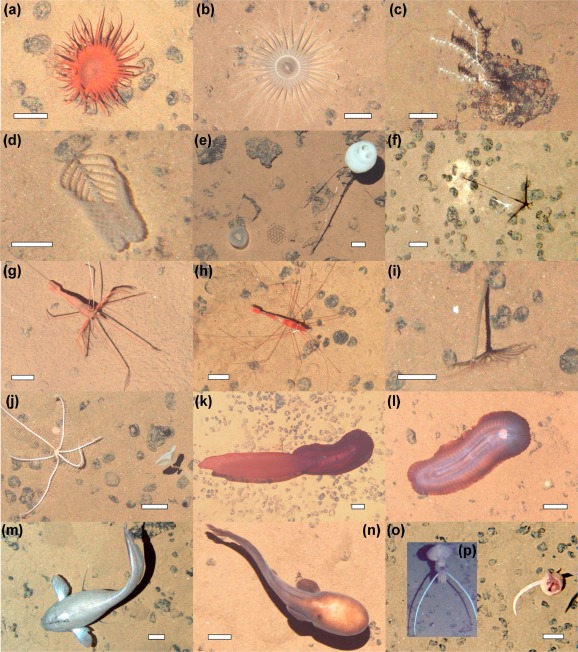

Critically, the current surge in interest in deep sea mining is driven by the transition to electric vehicles. Polymetallic nodules, once referred to as manganese nodules, are rich in cobalt, copper, and nickel: three metals that are essential to the current generation of batteries used in almost all electric vehicles. This positions the deep-sea mining discussion as an explicitly environmental debate, with both proponents of deep-sea mining and advocates for moratorium believing that they offer the most responsible path forward for the health of the planet. While supporters of moratorium argue that our understanding of the deep sea is insufficient to make a determination over the true environmental impacts of mining, deep-sea mining advocates insist that minerals from the seafloor offer the best and most environmentally responsible way to access the metals necessary for a transition away from fossil fuels.

The Metals Company believes that, even with incomplete knowledge, the data already demonstrates that deep-sea mining is superior to terrestrial mining and that the sooner they can go to the sea, the better off the world will be. “We are happy to consider any environmental factors in terms of [deep-sea mining],” stated the delegation from the Republic of Nauru, “on the premise that we are in a crisis in terms of the environment and Nauru’s impetus in driving this issue is that we need to move towards a net zero future or we don’t have a future.”

“We do not know what the future will look like, neither for us as delegates nor for the ocean,” stated the delegation from Costa Rica. “What is undeniable is that as representatives of our countries and of humanity we have an immense responsibility that fate has placed in our hands. We can get it right and truly commit ourselves to comply with [the ISA’s mandate to protect the marine environment]. Let us continue to work on the elaboration of the most robust and solid regulations, from the environmental point of view, but also from the point of view of transparency and governance; lets support, encourage and direct resources towards the necessary scientific research; and let us pledge not to submit or approve plans of work until we have filled the gaps in scientific information and can say without any doubt, that we can effectively protect the marine environment from any damage arising from activities in the area.”

The delegation of Costa Rica concluded with perhaps the most clear and succinct expression of why so many have worked so long to craft a mining code reflecting the values inherent in the principle of the Common Heritage of Humankind and remain willing to continue the arduous march towards compromise: “Seabed mining in the Area is different: it is the only resource we govern as a global community. It is also the only resource in human history that we have the opportunity to regulate before its exploitation is underway. That is why we have the enormous responsibility to do it well, taking all the necessary time.”

Featured Image: A digital image generated by the DALL-E machine learning algorithm based on the prompt “A group of people underwater in conversation surrounded by mining machines with a big clock in the background in the style of Salvador Dalí.”