JESSICA LEBER on OCEANS DEEPLY | 18 January 2018

While working for the Australian Department of the Environment, Christopher Cvitanovic, a marine protected area science manager, would encounter subscription paywalls that blocked his access to scientific studies. Article by article, he’d email the department’s library to request the full-text copy. Maybe he’d get it a day later, or maybe in a month.

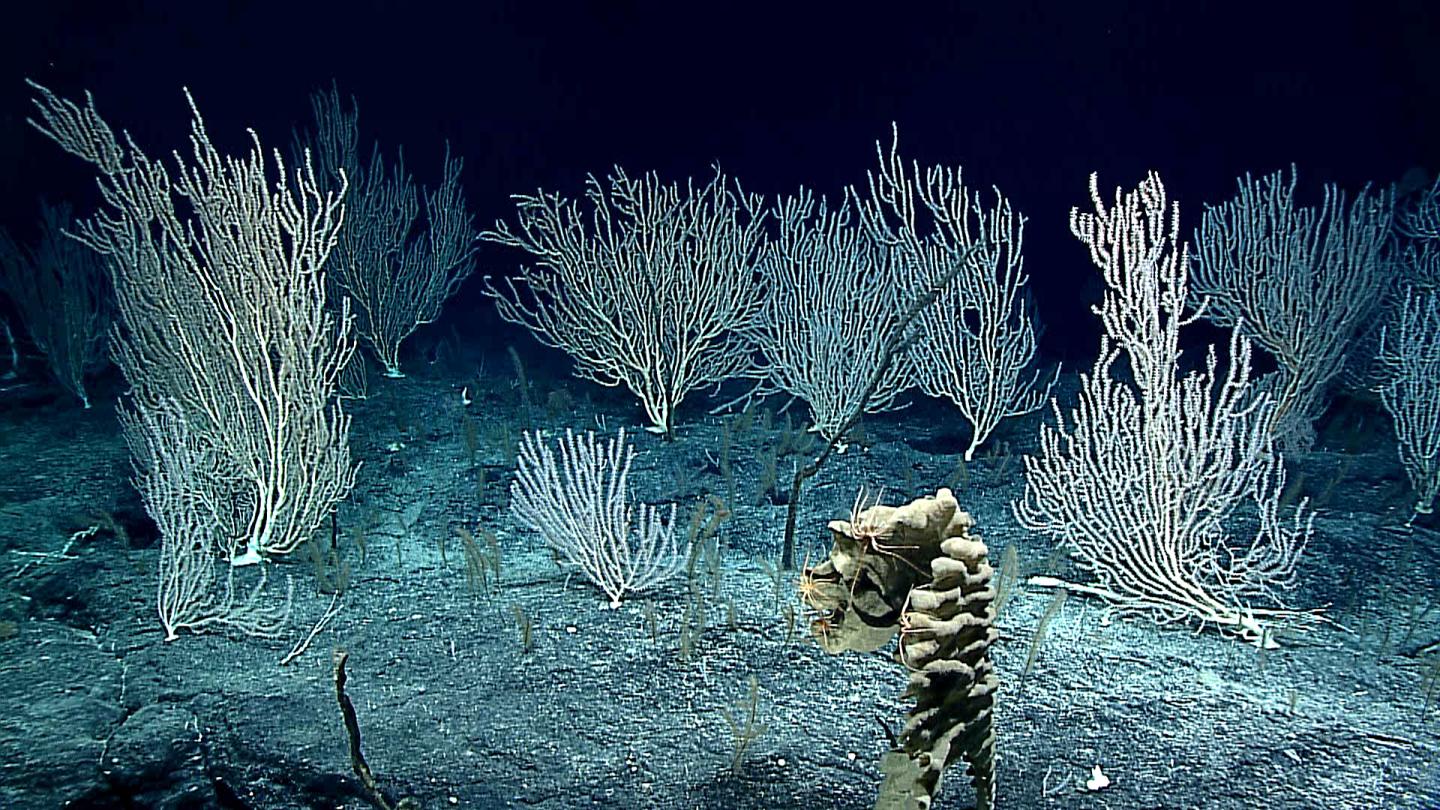

It could be a frustrating way to work as at the time he was developing standard monitoring guidelines that could be applied to Australia’s coral reef-dominated marine protected areas (MPAs). The project required looking up existing research that had been conducted in the fragile and imperiled ecosystems.

“We had real troubles accessing the literature,” he said. “You reached a point where you couldn’t do what you wanted to do. You knew the information was out there, and you couldn’t draw on it.”

Paywalls are, of course, only one small reason that organizations and governments working on ocean conservation struggle to use the latest science available, according to Cvitanovic, who left government work in 2015 and now studies these “knowledge exchange” barriers at the University of Tasmania. He has found they can include a variety of significant institutional, cultural, communication and outreach hurdles.

One study he conducted looked at the complex reasons why the results from a $36 million research program designed specifically to support decisions at Australia’s Ningaloo Marine Park were, in the end, barely utilized by park managers. Another of his studies found that primary scientific literature made up only 14 percent of citations in coral reef MPA management plans in Australia, Kenya and Belize. Subscription roadblocks were one of several factors at play, it found.

Yet many marine scientists, managers, advocates and policymakers around the world – from the poorest countries and organizations but also even the richest – have struggled to access research journals for years. The traditional model of academic publishing, in which major journals, published by a small handful of companies, charge subscription fees that can cost thousands of dollars for a single publication, has long made marine research harder to use for the very on-the-ground experts and practitioners it may need to reach.

Meanwhile, open-access publishing – which is free for readers – has been gaining ground in the past decade. However, it is still not the norm, partly because higher fees (anywhere from a few hundred dollars to $5,000) are often charged to study authors, their institutions or funders to free their research from paywalls, and far from all journals offer this option. These limitations can deter study authors from pursuing open access, especially younger researchers who are early in their careers or those from developing countries.

As ocean ecosystems decline and marine chemistry changes, many believe marine science doesn’t have time to lose in sharing research more widely, whatever the means. Despite its urgency as a crisis discipline, a 2014 study found that fewer than 10 percent of 20,000 papers in top general conservation science journals published since 2000 were freely accessible, compared to 30 percent in the field of evolutionary biology. Global statistics show that across all fields, 25 percent of academic studies in 2016 were freely available immediately after publication, a recent report from the group Universities UK found.

Many in fields that rely on marine research, however, now also see the opportunity to improve access as the internet brings significant changes to the wider and slow-moving academic publishing world. Platforms such as ResearchGate and Sci-Hub are now locked in copyright battles with publishers that echo those of the music industry and Napster two decades ago, when the internet began transforming the way people listened to music. In addition, more universities and some funders like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are actively embracing or even requiring open-access publishing, and institutions in Germany are banding together to negotiate innovative models to pay publishers, gain access to journals and make articles freely available to all.

Efforts to improve the availability of research studies are also more specifically taking shape within the marine science and conservation community, although they are still in the early stages.

“This kind of culture shift is really starting to play out now,” said Nick Wehner, director of open initiatives for Open Communications for The Ocean (OCTO), a Woodinville, Washington-based nonprofit that recently launched a marine science research “repository” called MarXiv. Its goal is to systematically make more marine research freely accessible.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, a big supporter of marine research, released its own open-access policy last April, requiring the scientists it funds to publish in journals that allow research to be freely available in some format a year after its publication. More marine research programs and universities are also working to support open-access publishing. For example, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) developed its voluntary open-access policy in late 2016, led by a graduate student.

Lisa Raymond, codirector of the joint WHOI and Marine Biological Laboratory library, believes there will be a slow shift to more open or affordably accessed science.

“There’s a whole lot of factors coming together that are eventually going to force some change in the economic model of [academic publishers], but I don’t think it’s going to happen immediately,” she said.

Even though it is one of the world’s preeminent oceanographic research facilities, WHOI itself still struggles to pay journal and database subscription costs because it’s not attached to a larger university, Raymond said. It devotes the majority of its library budget to fees, she noted, rather than expanding its relatively small staff, and is eager to push for better arrangements from publishers.

For OCTO, a moment of realization occurred several years ago when it tried to subscribe to a top journal publishing research about marine pollution. Wehner, who was lucky to have an office at the University of Washington where he could access journals, balked when he learned it would cost them $10,000, he said. “It was like, ‘You have got to be kidding me,’” Wehner recalled. “We were two employees.”

The group’s subsequent survey of a number of state government agencies in the U.S. working directly on marine planning and conservation found that none could easily access top subscription journals in the field. In OCTO’s newsletters that presented and summarized the latest ocean research to subscribers, they began labeling whether studies were free to access.

Click rates on free research were nearly twice as high as those behind a paywall, Wehner said, which is similar to other findings that show open-access research is cited more frequently. Many OCTO newsletter subscribers they surveyed said they relied solely on the group’s research summaries for subscription-only research, it turned out. “That is not how it’s supposed to work,” he said.

In October, funded by a grant from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, OCTO launched MarXiv and is encouraging study authors to submit their full-text papers legally and according to copyright agreements with publishers. Sometimes this is in the form of a “pre-print” before the publication is peer reviewed and sometimes as a “post-print,” following a one- or two-year embargo period after the paper is published online in the journal. Research that is already open access can also be submitted.

Meanwhile, the Nature Conservancy, one of the world’s largest environmental nonprofits, is also looking for solutions as it reduces the amount it spends on journal subscriptions, according to Lizzie McLeod, a scientist at the organization who helps lead the Reef Resilience Network.

The group, she said, has realized that it is prohibitively costly for it to maintain access to all the journals it needs, especially as conservation science has become more interdisciplinary, requiring access to, say, research from economists and social scientists in addition to biologists. The Nature Conservancy’s chief science officer, Hugh Possingham, is exploring new ways to access publications and has encouraged staff to develop relationships with universities or seek adjunct faculty roles, McLeod said. This helps them to collaborate on new research and share knowledge – and also has the benefit of providing staff with access to university library databases. A goal is to develop “informal networks” of journal access within the organization.

Researchers and institutions in non-Western and developing countries stand to gain the most as more research moves from behind paywalls. Those scientists are the most likely to lack access to research, grapple with communication barriers in emailing authors to request copies of studies and struggle to pay open-access fees when publishing their own research.

Juliano Palacios-Abrantes, a PhD student working on fisheries and climate change at the University of British Columbia, has signed up to be one of a handful of ambassadors for MarXiv who will spread the word in countries such as Mexico, Indonesia and Chile. Palacios-Abrantes, who went to college in Mexico and focuses his research there, says that today some fisheries researchers in Mexico prefer to publish in less well-known, local, Spanish-language journals to reach government fisheries managers in their country. Access to research journals is also hit or miss at universities, he said.

Asha de Vos, a whale biologist in Sri Lanka who is on the steering committee for MarXiv and is a vocal advocate around equity issues in marine science, has also seen that most local institutions can’t afford journal access. “Paywalls discriminate and, what’s worse, prevent us from tapping into the minds of the millions of capable and intelligent problem-solvers across the world,” she said in an email.

Major academic publishers, which have long been criticized for high profit margins, especially when research is funded with public money, have been increasingly collaborating to improve access. Springer Nature and Elsevier both pointed Oceans Deeply to a program they are involved with called Research4Life, which provides low-cost or free access in developing countries to environmental research and noted they run programs that encourage and assist authors and institutions in easily sharing or archiving free copies of their work. (Another publisher, Wiley, declined to comment.)

“Elsevier believes that lack of access to knowledge is one of the main limitations to human development,” Tom Reller, Elsevier’s vice president for communications, said in an email.

McLeod of the Nature Conservancy also noted that access is not just an issue for publishers. More funders and professional societies need to be encouraged to support costs for open-access publication and memberships, she said. Researchers, she added, should make more effort to make their papers available and, sometimes more importantly, disseminate their findings in other ways, through blogs, press releases or articles that get translated into other languages. One problem, Cvitanovic’s research has found, is that these issues go beyond mere access – the incentives and timelines of researchers in communicating their findings do not always line up with the needs of on-the-ground conservation workers.

MarXiv is in its very early stages, with only a handful of papers available so far, but it is modeled on a number of similar repositories in other fields.

The oldest and most successful is arXiv, the physics, computer science and mathematics database founded 26 years ago that recently celebrated its one billionth download and receives 10,000 paper submissions a month. In these fields, arXiv has gained widespread acceptance as the place to hash out new research findings before the lengthy process of formal peer review for a journal publication, speeding up the pace of research. Famed physicist Stephen Hawking, for example, submitted his latest research on black holes there last year before any journal.

However, it has taken years for this model to become accepted in the physics field. MarXiv will surely face challenges in raising awareness and educating marine researchers about their rights in their agreements with journals. Younger scientists may be more likely to adopt pre-print and post-print repositories as an alternative to publishing open-access research in the journals themselves. They often, understandably, don’t want to forego publishing in top-tier journals that can help advance their careers, Raymond noted. The fees for open access can also be more difficult for them to pay.

“It is hard, though, for people like us, early career scientists who publish in open access, because it is expensive,” said Palacios-Abrantes.

McLeod noted that paywalls can limit the development of review papers that synthesize a large number of studies. Such analysis is important because, even when government managers do have access to all the journals in the world, they may not be able to read every study. Easily available review papers, she said, are crucial to transferring knowledge and informing conservation action, a major goal of the Reef Resilience Network.

“We recognize that managers around the world working on coral reef systems are overwhelmed addressing existing threats facing marine systems,” she said. “There are too many fires they are trying to put out and they don’t have time to sit there and dig through stacks of scientific publications.”

Researchers may trust a nonprofit more than newer, controversial platforms that are disrupting academic publishing today and face copyright lawsuits from publishers. “I had begun to use sharing platforms like ResearchGate and Academia.edu, but these platforms are/will change their business model and find other ways to profit from our work,” Wesley Flannery, a lecturer at Queen’s University, Belfast, who recently submitted a paper to MarXiv, said in an email. “I trust the team behind MarXiv,” he said.

This article originally appeared on Oceans Deeply. You can find the original here. For important news about our world’s oceans, you can sign up to the Oceans email list.